This picture by BL SONI was published in The Free Press Journal. Credit: https://www.freepressjournal.in/mumbai/mumbai-worlis-bdd-chawl-to-burn-coronavirus-effigy-for-holika-dahan

As I write this post in the midst of the COVID-19 pandemic, our lives are being unprecedentedly forced into isolation and restricted mobility. Our socialisation of life and death is deprived of the communion of togetherness. ‘Lock-downs’ and ‘circuit breakers’ are muting and mutating the sonorous profile of our inhabited spaces. Days are strangely still and noiseless.

People from diverse corners of the planet make sense of these bizarre circumstances by putting into use the repertoires of worldviews, traditions, and authoritative knowledges that are available to them. Secularist believers entrust their faith into biomedicine and the hope of the discovery of a vaccination.

A vegetarian Hindu leader explained that the virus is an avatara descended on earth to restore the universal balance which deteriorated because of the increasing numbers of meat-eaters. The Islamic State narrative justifies the pandemic as a divine retribution to punish China for having brought death to many Uyghur Muslims. Feng Shui masters ascribe it instead to a preponderance of the metal and water element over fire in the early year of the Rat. Competing systems specialised in establishing relations with the cosmos and the non-human have reassuring answers and persuasive explanations, which will shape the behaviour of numerous people, their choices, consumption, diet, and beliefs.

To take into account the multivocality of religious responses and ritual innovations that surfaced after the beginning of the COVID-19 pandemic, after receiving WhatsApp chains of prayers addressed to an innocuously New Age-ish, apolitical and vague ‘healing angel’ in February, I started to discuss with my cluster a research initiative on Religion and Coronavirus.

We decided to offer an easy and accessible platform to encourage reflections, exchange and discussion on the various ways in which religions and societies are mutually shaped and transformed during a pandemic. We called this online platform CoronAsur because early in the timeline of the global infection, people in Mumbai started to build effigies of the virus utilising the traditional iconography of an ugly-looking demon.

These effigies, nick-named Coronasur, have been burnt by the city-dwellers for auspicious and apotropaic purposes during the festive occasion of the full-moon ritual preceding Holi, the famous “festival of colours”. Therefore our title: CoronAsur: Religion and COVID-19 – where Corona stands for Coronavirus (in case this wasn’t clear), and Asur (asura in Sanskrit, with etymological descendants in many Asian languages) means demon.

Mumbai Hindu dwellers were not the only ones to creatively put into use their cultural tool-box of symbols and stories in order to cope with new traumatic realities. For instance, Chhau dancers of eastern India used their elaborate masks and traditional repertoires of movements to enact the story of the battle against the Corona-demon – but with only two or three dancers, as opposed to a full troupe – to communicate the importance of maintaining social distance (see their dance here).

Scroll-painters and itinerant singers from West Bengal reproduced the story of the spread of the Coronavirus disease through their unique folk art, employing the demonesque features similar to those that they had previously adopted to depict the HIV/AIDS disease. The painter and singer Swarna Chitrakar has kindly allowed us to use her painting of the Corona demon for this blog. More information about her painted scroll and about the tradition of fever-demons in Bengal and in South Asian folklore will be available in our next posts.

CoronAsur in Chau dance. Picture by Amit Singh Deo, published on Sangbad Pratidin: Credit https://www.sangbadpratidin.in/bengal/purulia-chhau-artists-spread-awarness-about-the-effect-of-coronavirus/

This research blog is immersed in the Asian plurireligious as well as secular city of Singapore, but we are also interested in global and comparative lenses and will host contributions from regional and transnational scholars, social actors and practitioners from various religious communities.

These perspectives will be valuable in understanding the long-lasting effects of the radical changes that have impacted the meanings of spiritual well-being, religious gathering, and ritual – at the time of social distancing and coercive epistemologies of hygiene.

Contract tracing operations in Singapore, Malaysia, and South Korea have confirmed that some major clusters of virus diffusion were represented by large religious gatherings. At present, religious communities are prevented from gathering in several nations.

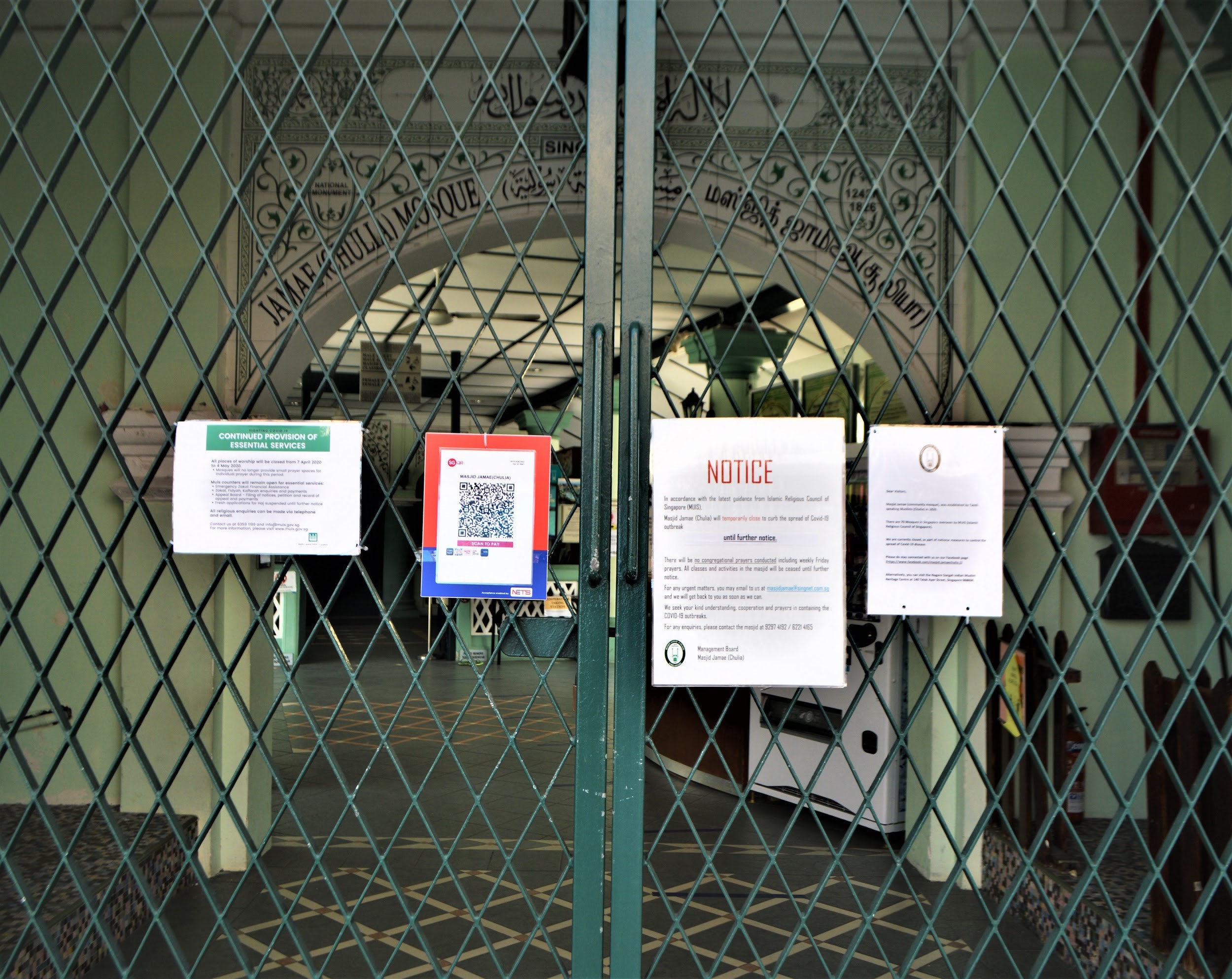

Some resisted the prohibition, while others went digital, utilising all possible technological means at their disposal to record, livestream and reproduce religious experiences. When legally allowed to assemble at all, Catholic Christians are now refraining from shaking hands as a sign of peace. In some churches, holy water can be applied with disposable q-tips. Of most places of worship in Singapore, the only visible feature is a tightly locked entrance, with clear signs that, where possible, redirect the devotees to online activities.

Masjid Jamae, one of the earliest mosques in Singapore, located on South Bridge Road. Photo by the author (April 2020).

These new practices provide a unique platform to interrogate the theoretical frame of the “sensory dimension” of religion. The “embodiment” paradigm and the “sensory turn” persuaded religion scholars to pay attention to religiosity in terms of sharing experiences of touch, sound, smell, partaking of food, involving vicinity of bodies and contact among practitioners. Are we witnessing instead a disembodiment and a de-sensorialisation of religious communities and their ritual practices?

With ritual ingredients commodified on WhatsApp and religious functions broadcast on dedicated YouTube channels, devotional bodies are separated and practitioners are participating remotely in their communal occasions of divine con-tact. Is new media utilised in a vacuum of embodied and sensorial aspects of religious engagement? Or shall we rather understand digital forms of religious mediation as sensory experiences on their own right?

These are but some examples of how this blog aims to tackle emerging phenomena at the interface of religion and society and develop new empirical questions.

Far from surrendering to the enforced separation of bodies and senses, in the lack of certainties and in the need for hope and comfort, quarantined Italians gathered on their balconies with their voices and with improvised instruments to share a collective experience of socially distant and yet healing sound.

Indian crowds erupted on their verandas during a Coronavirus-related curfew to bang on metal plates, blow into conch shells, and chase away the demon/disease with communal noise-making.

In the spectral silence of the past Easter Sunday, celebrated in empty churches and in isolated households, the moving voice of famed tenor Andrea Bocelli reverberated in the electronic devices of thousands of remote listeners as he sang in front of the Duomo of Milan in a hauntingly deserted square,

The meaning and the acoustics of a ‘real interaction’ have changed irreversibly. The lines between offline and online religious experience are blurring. The background noise of urban activities has faded. The streets and the temples might be more quiet than ever. But as I type on my keyboard, it sounds like the birds are singing much louder than usual.

contributed by Carola LOREA, 18 May 2020

Disclaimer: The views and opinions expressed in this article are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the position of the blog editorial team or the Asia Research Institute.