Islamophobia in COVID Times: Building Transnational Muslim Solidarities Online between India and the Gulf

contributed by Sanam Roohi, 18 November 2021

Manufacturing a crisis

The World Health Organization declared COVID-19 as a global pandemic on 11 March 2020. While epidemiologists were warning of community spread in some pockets of India by then, the Indian government had declared that COVID-19 was not an emergency. Yet, in a sudden move that took the nation by surprise, the Indian Prime Minister declared a three-week strictly enforceable lockdown on 24 March 2020, a provision that was followed till June and widely termed as draconian. This sudden declaration brought all forms of surface transportation to a grinding halt plunging many of India’s 139 million internal migrants working in the informal sector into an unprecedented humanitarian crisis. To deflect the critical attention from the sufferings of the daily wage labourers, the Hindu nationalist government following the old template of Islamophobia manufactured a new crisis putting the blame of the virus spread on the Muslims. This blogpost discusses the online manifestation of this scapegoating of the Muslim minorities that produced the hashtag #CoronaJihad on Twitter. Further it discusses how this Twitter trend was not only combatted by the Indian Muslims online, but for the first time found support among the prominent Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC) citizens. It ends by briefly highlighting the ramifications of this online solidarity on Indo-Gulf relations.

Timeline of the early virus spread in India in 2020

|

Date |

Event |

|

25 – 26 February |

Namaste Trump event in Ahmedabad city in West India |

|

5-21 March |

Jamaat annual meeting in Delhi |

|

11 March |

WHO declared COVID-19 a pandemic |

|

12-13 March |

Indian government says COVID-19 not an emergency |

|

20 March |

Officially only 300 COVID-19 infection cases |

|

22 March |

Day long Janata curfew |

|

24 March onward |

Stringent lockdown extended till June leading to the ‘migrant crisis’ |

|

25-26 March |

Early report on infection among Jamaat attendees |

|

April – May |

Jamaat news dominates in mainstream Indian news channels |

Figure 1: Table prepared by author based on news reports

The ‘Muslim’ problem

As daily wage earners, the lockdown left millions of migrants in India without a job or pay and forced them to walk hundreds of kilometres from their temporary shelters in major Indian cities to their villages, largely in the eastern parts of India. Images of migrants walking back on foot caught the attention of the international media and humanitarian agencies alike but the government justified its strict lockdown measures as a necessary step to control the virus. During this early stage while ground surface transportation was stopped, repatriation flights from across the world continued to bring overseas Indians back into the country. Even as the country was grappling with the domestic migration crisis, news of Tablighi Jamaat or TJ (a Muslim proselytizing group who had gathered for their annual convention in Delhi) members testing positive for COVID-19 started to emerge by the end of March and soon became the topic of primetime news discussion. With it, the media narrative in online and offline spaces shifted swiftly and decisively from the migrant crisis to the ‘Muslim problem’. The TJ in particular and Muslims in general became the target of coordinated Islamophobic attacks in online spaces where Muslims were charged with deliberately spreading the virus. This episode became an important instance of demonizing the Jamaat members who were jailed for flouting COVID norms but then acquitted by a Delhi court in December 2020. The TJ founded in India in 1927 as a global Islamic reformist movement that aims to spread authentic ritual and demeanour as practiced by Prophet Muhammed among Muslims has remained apolitical since its inception in 1927. Once the news of the first Covid-positive cases broke, the TJ was denounced on social and mainstream media platforms as a terrorist group with primetime news on TV doing shows for weeks uncovering its linkages with global jihad and claiming that spreading the virus was one key way in which it engaged with jihad. The news was soon followed by unconstitutional calls to boycott Muslims, and multiple incidents started to be reported throughout the country.

Twitter emerged as a significant platform where members of the ‘Hindu Twitter’ or HT (self-identified supporters of the religio-nationalist ideology of Hindutva) amplified such news which ‘Indian Muslim Twitter’ or IMT (who while divided on many issues vehemently oppose the Hindutva ideology online) repeatedly flagged as false, aided by fact-checking sites, especially Alt News. Online Islamophobia is a global phenomenon not limited to India. However, in the TJ event aftermath, a new development of international significance transpired on Twitter. With hashtags and tagging of international Twitter users (particularly journalists and human rights groups), this online hate campaign against the Muslims drew the attention of several members from the Gulf countries (temporary home to roughly 8 million Indians) who joined the cause of combatting hate speech and Islamophobia online. Nevertheless, the pandemic also threw open a chance to build new forms of transnational solidarity between Indian Muslims and Arab citizens from the GCC countries who raised their voice against this coordinated attack maligning Indian Muslims and Islam.

Building transnational solidarities

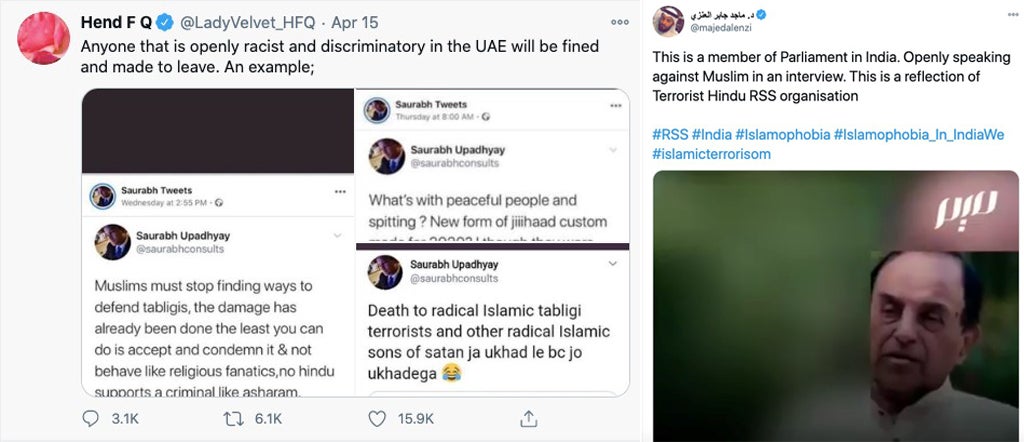

Twitter for the first time saw the convergence of Arab Muslim voices from the GCC countries out in support of Indian Muslims who have been facing increasing criminalization under the Hindu populist regime. Therefore, even as the online space saw extreme speech in India particularly targeting Muslims, it also became a platform to counter it through transnational forging of online solidarities that centred around the premise of the unity of believers of the same faith and defending believers of a shared religion. Among these voices were Princess Hend Al Qassimi of the United Arab Emirates (UAE) who promised to impose harsh punishments on Indians living in the gulf country who engaged in Islamophobia. She was joined by other prominent Gulf nations’ citizens who promised the same, projecting immense distaste for some of the tweets shared by members of the Hindu nationalist Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) and other HT members (figure 2). Earlier atrocities against Muslims during the Delhi riots in January – February 2020 were also emphasized anew by these Arab social media users who were incensed as well as surprised by the prevalence of rampant Islamophobia in India.

The solidarity shown by a few GCC citizens on the plight of Indian Muslims invigorated the IMT handles (or users) who felt that this attention would pressurise the Indian government to curb the atrocities its supporters and sympathizers commit on Indian Muslims. While IMT handles tagged these concerned GCC citizens on Twitter on any news articles reporting brutalities committed on Indian Muslims, they especially brought to their notice Islamophobic content posted online by Indian migrants in the Gulf. In response, these prominent Arab Twitter handles not only tweet in support of Indian Muslims or against the charges of Corona Jihad, their interventions went further. News of Indians working in the Gulf participating in online hate speech who were being forced to resign from their jobs started to be reported from Saudi Arabia, the UAE and Kuwait. These interventions penalized Hindu Indians working in the Gulf countries who had posted hate filled Islamophobic speech online accusing or even abusing Indian Muslims or Islam.

Figure 2: Tweets by prominent Gulf handles in support of Indian Muslims

The Persian Gulf nations are home to some 8 million Indian migrants who cumulatively send the largest share of remittances to India, a sizeable number of whom have overstayed their visas. When the virus crisis hit the Gulf countries, their priority was their own citizens rather than migrants. Although no discrimination in terms of receiving treatment was reported from among the COVID infected migrants, news that the Gulf states were forcing India to expatriate Indian migrants from its soil had surfaced during the same time when online Islamophobia was reported in India. Thereafter, one fallout of the pressures exerted by the Gulf nations was that India agreed to send flights and ships to bring back its “distressed” nationals in early May 2020.

Interestingly the engagement of the Gulf citizens with online Islamophobia in India subsided thereafter, converging with the news of the repatriation of Indians from GCC countries. But as the COVID induced incidence of Islamophobia shows, Twitter also fleetingly built online solidarities that did not exist or were not possible before. However, such solidarities do not take place in a political vacuum, and international relations and perhaps foreign policy eventually took precedence over humanitarian concerns.

Disclaimer: The views and opinions expressed in this article are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the position of the blog editorial team or the Asia Research Institute.

South Asia | Southeast Asia | East Asia | Other Places | Hinduism | Buddhism | Islam | Christianity | Other Religions

Sanam Roohi is an Alexander von Humboldt fellow at the Centre for Modern Indian Studies, University of Göttingen and an associate fellow at the Max Weber Kolleg, Erfurt. As a social anthropologist, her work straddles the themes of embodied migration infrastructures, transnational resource flows and their ramifications on caste- and religious inflected community formations within the Indian diaspora. Roohi is also on the editorial board of Comparative Migration Studies journal.