Covid-19, Medical Pluralism, and the Democratization of the Tibetan Buddhist Sodality

contributed by Tanisha Verma, 27 January 2022

“om tare tuttare ture soha”

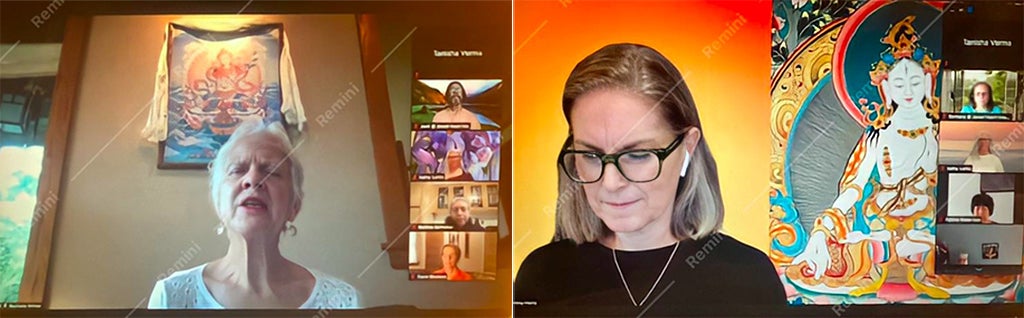

Adherents chanting this chain of words in unison, closed eyes, their focus on a fancied light; the light radiating, transforming into the Noble Wish-fulfilling Tara. I watched as practitioners from all around the world congregated to offer prayers to the holy noble White Tara, imagining her sitting on a lotus, a luminous aura surrounding her. We were all virtually present at the White Tara guided healing meditation event organized by the Jewel Heart Tibetan Buddhist Learning center, originally based in Ann Arbor, Michigan.

The devotees were told by the meditation facilitator to visualize a brilliant light emanating from the syllables of this repeated rhythmic phrase or mantra; a light that collected the essence of inexhaustible vitality and the powerful blessings of wisdom and health. The feminine counterpart of the bodhisattva Avalokiteshvara, the White Tara, is prayed by pious Tibetans to gain healing, health, and longevity. Confronted with an all-pervasive pandemic, it was no wonder that adherents from all walks of life gathered to offer prayers to the White Tara, to receive her compassionate healing.

Figures 1 and 2: Screenshots of two different White Tara meditation events organized by the Jewel Heart Organization

I attended this guided healing meditation session thrice, and my experience each time was different; each time there was a different meditation facilitator, and a different style of conducting the session. The only thing consistent during these sessions was the recitation of the White Tara Mantra. It was here I observed that while the Tibetan tradition and medicine offered protection and the hope of healing to believers, the exercising of its practice varied, depending upon the context of the practitioner. Consequently, I wanted to gain a better understanding of the plurality of performances of this contemporary Tibetan tradition, and its effects on the syncretism between Tibetan medicine and modern bio-medical healthcare approaches to healing in the covidian milieu.

Virtual Ethnographic Method

For this investigation I used mixed-methods: I conducted semi-structured interviews, and administered surveys to three distinct groups of people: Tibetan Medicine practitioners, Tibetan Buddhist monastic academics and nuns, and lay Buddhists. In light of the Covid-19 pandemic, research was conducted through participant observation through the viewing of various virtual performances of asynchronous and synchronous cyber-rituals and theological adjacent sermons.

Given the recent institutionalization of public safety measures, there has been a transformation of sacred spaces and ritual performance, and an ubiquitous embrace of digital transformation. I was thus intrigued by devotees' engagement in ritual activity through the modality of online sacred spaces, relative to a ‘real’ place of worship. Media theorist Stephen Jacobs argues that a virtually crafted sacred space “could neither replace nor fully replicate the physical co-presence of fellow worshippers.” Nevertheless, he asserted how it is also recognized that online interaction is in fact a real experience.

Jacobs builds on Mircea Eliade’s (1983) suggestion of how a particular object “might appear to be simply a mundane object, but for the believer, it has ceased to be simply another rock or tree—rather, it is transformed into something sacred, something set apart.” Profane space in this case is consecrated, through one's faith and belief, and transformed into sacred space, leading to information in cyberspace “quite literally” having an architecture. Accepting the validity of virtual sacred spaces in the eyes of the devotees, I conducted participant-observation in these virtual sacred platforms during synchronous and asynchronous events.

Re-defining the Tibetan Buddhist Praxis

The customs of the Tibetan Buddhist tradition are incongruously practiced. This disparity in practice may be rooted in the heterogeneous nature of the culture, social, and political dynamics affecting the Tibetan diaspora network in exile globally. It is important, therefore, to consider the Tibetan Buddhist tradition through ethnography, and the institutionalized forms it has embodied in the occident. Ana Cristina O. Lopes, discusses this “re-signification” of the Tibetan Buddhist tradition, arguing that this supposed global fragmentation of the Tibetan Buddhist network in exile produces various different re-interpretations of the practice of Tibetan Buddhism globally, thereby lacking homogeneity. Lopes highlights a principal character who led the initial Tibetan cultural circulation within the new context of the diaspora; she asserts how the public presence of the Fifth Dalai Lama played a critical role “in the construction of the personas of all Dalai Lamas.” Hence she propounds how the ongoing “autonomization” (the process of making a practice or a performative ritual self-determined and autonomous) of the Tibetan Buddhist practitioners globally “contribute[s] to the creation of Tibetan Buddhist culture on a planetary scale”—an insight underscored by the fieldwork findings that I discuss below.

The Tibetan Buddhist Transnational Field

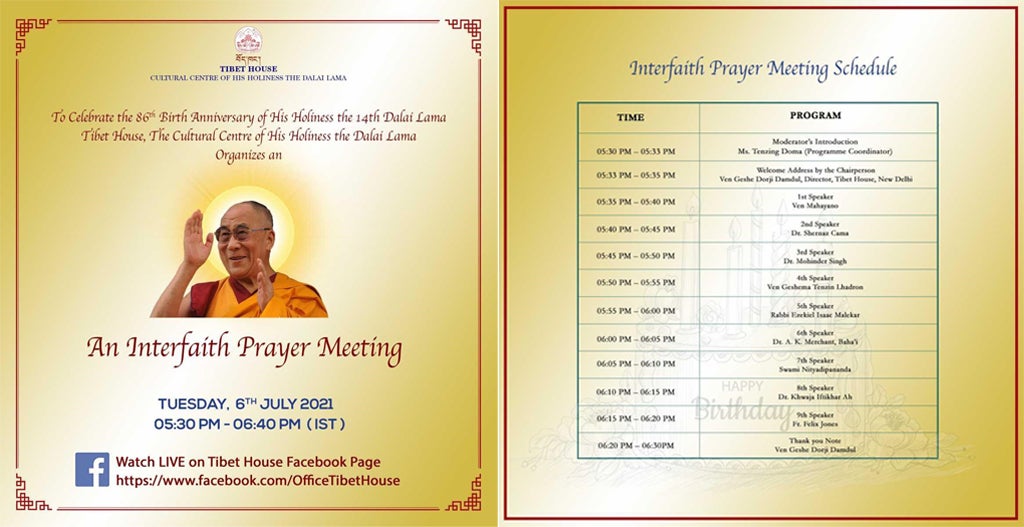

During a global health crisis, the earnest desire to pray to gain strength and protection is ubiquitous, leading to the subsequent rise in virtual worship services of all faiths. I attended an interfaith virtual prayer meet, hosted by the Tibetan House in New Delhi, which platformed representatives of many of the world’s major religions. The intention behind this convocation was to offer all-embracing prayers to the world to combat Covid-19. This apparent democratization of religious paradigms and faith-based diplomacy, led of course by the Tibetan Buddhist religion, foregrounds a contemporarily expansionary movement of the Tibetan tradition conducted by the diaspora in exile—a movement which I call the Tibetan traditions’ broadening approach.

Figures 3 and 4: Invitation card for the Interfaith Prayer Meet broadcasted worldwide

Figure 5: Screenshot of the virtual Interfaith Prayer Meeting, inclusive of some religious leaders, on the 6th of July, 2021.

The broadening approach of Tibetan Buddhism can be attributed to the multiplicity of levels in which religion and politics interact in the Tibetan diasporic context, as substantiated by Lopes’s academic work. Lopes argues that the development of the Tibetan Buddhist diaspora as a “multi-cored” network is engendered by two “formative moments” in the shaping of the Buddhist transnational field. The first is the ‘outward’ movement which began with the escape of the “Fourteenth Dalai Lama from Tibet and the establishment of several Tibetan refugee settlements in India, Bhutan, and Nepal”, implying how this movement helped conceive a larger Tibetan cultural consciousness globally. The second is an ‘inward’ movement honing on the “reception of the Western ideal of democracy by the Tibetan exile community.”

Tibetan medicine’s expansionary ambitions extend to the infiltration of modern biomedical healthcare practices in Tibetan medicine itself. This interference was reiterated in an asynchronous event I attended entitled “Coronavirus; Finding Relief through the Bodhisattva’s way of life.” This event was organized by The Jewel Heart, led by Demo Rinpoche. This event was initially live streamed, but recorded for archiving purposes and separated into a series of 25 videos. The premise behind this event was to apply the learnings of Shantideva’s Guide to the Bodhisattva’s Way of Life, in an attempt to morph the crisis of the pandemic into a beneficial period. During his lectures, Demo Rinpoche further substantiated the Tibetan tradition’s broadening approach. Tibetan expansionism was apparent in the monks' assertion that one's engagement with their bodhichitta, an awakened mind that strives towards compassion for all sentient beings, includes following the public health precautionary measures during Covid-19; he asserted how simply admiring the bodhicitta mind isn’t enough, one has to act on their intentions. This merging of public health measures with traditional Tibetan Buddhist practices affirms what Lopes calls the ‘inward’ movement of the Tibetan exile community, and what is more commonly known as Buddhist modernism.

Figure 6: Screenshot of Demo Rinpoche giving his lecture on Coronavirus: “Finding Relief through the Bodhisattva’s way of Life”.

This democratization and subsequent secularization of the Tibetan Buddhist heritage, according to Lopes, is a “strategic move” that has licensed the Tibetan government to align with Western sodalities. Pordié asserts how the medical practices and the ideologies that neo-traditional healers embody allow them to gradually penetrate the culture (social and medical) of Western sodalities, considering their holistic, “energy-base, even transcendental” medical methodologies (especially given the West’s increasing recognition of holistic healing and the emergence of the mind/body/spirit connection consciousness in modern medical healthcare.) However, altering the medical methodologies of traditional Tibetan medicine to align western medical ideologies may naturally lead to its own warping. Pordié identifies how a kind of selective accentuation of characteristics of Tibetan medicine is typical of neo-traditionalism. However, the diffusing of “partial, approximate or distorted images of Tibetan medicine,” used primarily for the intention of legitimization, raises questions about the identity and authenticity of Tibetan medicine.

Epidemiological interference: Tibetan Medicine and Covid-19

Amongst the many inefficacious therapies the pandemic has borne, one of its more productive impacts is a renewed interest in the ancient and traditional system of Tibetan Medicine (Sowa Rigpa). Nonetheless, Dean Yogi, a Sowa Rigpa practitioner based in Malaysia that I conducted a phone interview with, acknowledged that the intricate production of Sowa Rigpa medications coupled with its treatment’s slow efficacy, pose Sowa Rigpa as a non-viable remedial option for the Covid-19 virus relative to modern medication. This opinion is covertly reflected in various critiques of Tibetan medicine’s efficacy, as presented in Tawni Tidwell’s article in the Society for Cultural Anthropology as well. However, Dean Yogi expressed that in places other than Nepal and Tibet, Sowa Rigpa is actually perceived more as a prophylactic than a cure for Covid-19, through the chanting of mantras, the obtainment of special Tibetan pills, and the hanging of prayer flags, not as provision for “healing” from the virus—an insight underscored by Gerke, a social and medical anthropologist researching Sowa Rigpa, as well. That is where modern healthcare infiltrates Tibetan medical initiatives; the pluralistic nature of the Tibetan Buddhist sodality ensures the incorporation of contemporary public health measures.

Being a holistic practitioner who believes in the “synergy” of all medical repertoires, Dean Yogi vehemently asserted that in addition to chanting healing mantras, the importance of modern healthcare measures (social distancing, the wearing of masks) in combating Covid-19 cannot be underestimated. Additionally, Tenzin Dadin, a monastic scholar I interviewed, insisted that although the Tibetan Buddhist tradition focuses on karmically generated illnesses, one can’t always rely on karma, “otherwise we land up doing nothing.” Consequently, Dadin underlined the importance of resisting ignorance and following public health precautionary protocols as an aversion to bad karma. Gerke echoes this apparent medical syncretism by mentioning that the wearing of face masks, the chanting of mantras and taking steps to repel bad-karma, while based on seemingly different epistemologies, do “not contradict each other in Tibetan responses to Covid-19, rather they are a part of the multivalent resources that people mobilize to feel protected.”

Gerke delineates this ‘multivalency’ by clarifying the reasons behind how the successful conjugation of Sowa Rigpa and modern public health measures have conspired. She elucidates how the employment of traditional practices are intended to engender “spaces of emotional stability and ethical conduction” in the aspiration of rearing less fear and panic, and more empathy.

Dr. Karma Tashi Choedron, a monastic academic I virtually interviewed who works at the Kuala Lumpur campus of the University of Nottingham, posited that the Tibetan tradition’s view on illness and affliction (amid this public health crisis) is that it is we who generate the causes and conditions which we collectively experience “through the three mental poisons of ignorance, hatred and attachment.” Hence, it is we who can reverse it by purifying our afflictive emotions and generating more goodwill through compassionate acts. Inherent in all these claims, there is a clear implication of traditional Tibetan medicine fostering a sense of cognitive equanimity during the public health crisis, to a larger extent, perhaps, than modern biomedical measures ever could.

These complex ‘webs of potency’ (Gerke 2020) that exist amid this public health crisis, and their reliance on public health systems, along with the various preventive measures employed during this covidian milieu (social distancing, mask wearing etc.) brings to the surface a significant point: that there is more to health than mere healthcare.

The transformations of Sowa Rigpa and the Tibetan Buddhist tradition, in regards to the exercising of its practices, during the Covid-19 pandemic has crystalized the versatility of the Tibetan Buddhist tradition. Its ability to transcend borders due to its multilayered epistemological responses to Covid-19 is truly novel. Tibetan Buddhist tradition and medicine have stood the test of time thus far; but would they be able to sustain their presence in the future? Only time will tell.

Bibliography: Callegari, Ilaria. “Book Review, Tibetan Buddhism in Diaspora: Cultural Re-Signification in Practise and Institutions.” Journal of Global Buddhism, Vol. 18 (2017): 184-188. http://dx.doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.1284432

Gerke, Barbara. "Thinking through complex webs of potency." Medicine Anthropology Theory 7, no. 1 (2020). https://www.researchgate.net/publication/342022044_Thinking_through_complex_webs_of_potency_Tibetan_medical_responses_to_the_emerging_Coronavirus_SARS-CoV-2_epidemic

Laurent Pordié. Tibetan medicine today: neo-traditionalism as an analytical lens and a political tool. Tibetan Medicine in the Contemporary World. Global Politics of Medical Knowledge and Practice, London and New York: Routledge, pp.3-32, 2008, Series of the Needham Research Institute. halshs00516479 https://halshs.archives-ouvertes.fr/halshs-00516479/document

“Prayer To The Noble Tara .” Jewel Heart, Jewel Heart Buddhist Learning Centre,

https://www.jewelheart.org/wordpress/wp-content/uploads/2020/03/Prayer-to-Noble-Tara.pdf.

Stephen Jacobs, Virtually Sacred: The Performance of Asynchronous Cyber-Rituals in Online Spaces,

Journal of Computer-Mediated Communication, Volume 12, Issue 3, 1 (2007), Pages 1103–1121, https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1083-6101.2007.00365.x

Tidwell, Tawni. “Covid-19 and Tibetan Medicine: An Awakening Tradition in a New Era of Global

Health Crisis.” Society for Cultural Anthropology,

Disclaimer: The views and opinions expressed in this article are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the position of the blog editorial team or the Asia Research Institute.

South Asia | Southeast Asia | East Asia | Other Places | Hinduism | Buddhism | Islam | Christianity | Other Religions

Tanisha Verma is a sophomore at Yale-NUS College. Currently undergoing her Bachelors training in Cultural Anthropology and Economics, her research interests lie in embodied religion and faith-based mediations, health, illness and well-being as social and cultural constituents, and the intersection of economic development and the anthropological approach.