Taoist Medical Texts, Drug Discovery, and Pandemics

contributed by Jianan Huang, 20 Apr 2022

Throughout history, there has been a relatively long-standing connection between Taoism and medicine (Ho 2007). Nonetheless, Taoist medicine is currently outside the purview of biomedical scientists and sometimes is labelled as a heterodox medicine (Unschuld 1979: 18). This situation has gradually changed in recent decades, especially in terms of drug discovery. This article would try to present some preliminary efforts of drug discoveries inspired by Taoist medicine in the context of global outbreaks of epidemic diseases, in the past as well as in the present. Before the formal discussion, it also should be acknowledged that the modernization of traditional medicines is a complicated and controversial topic, entangled with political and identitarian dimensions. Traditional medicine gained ample attention in pandemic treatment; its proclaimed effects are sometimes overstated because of media promotion and political propaganda (Zhou 2021).

Anti-Malarial Drugs and Taoist Priest Ge Hong

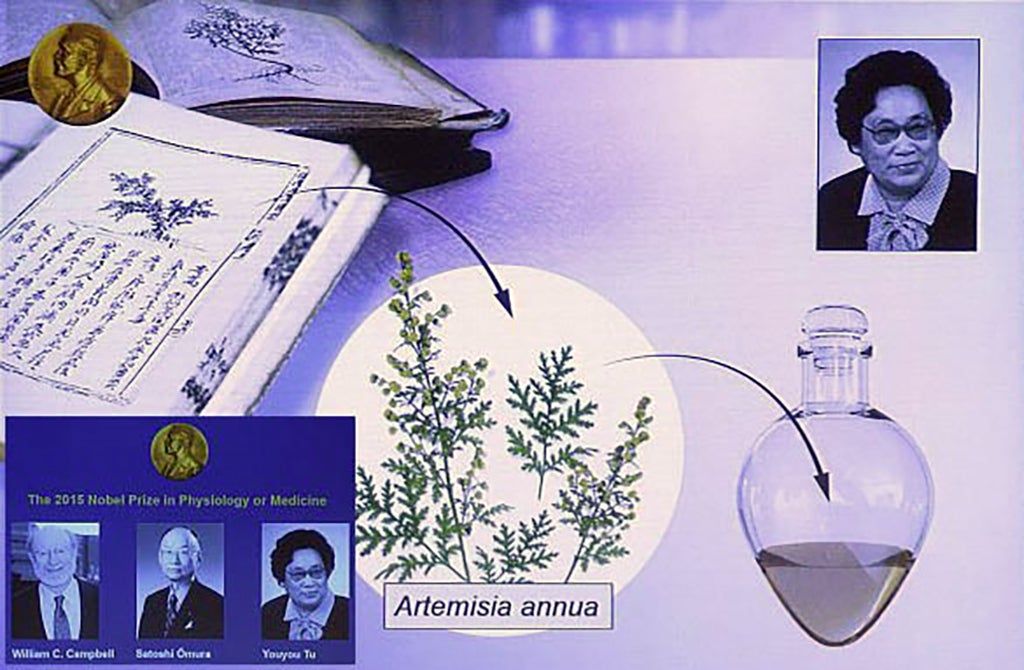

The first milestone appeared in the 1970s, when the team of Tu Youyou (1930–present) developed the drug Artemisinin (C15H22O5) from Artemisia apiacea (Qinghao). As a Chinese medicinal herb, Artemisia apiacea has been used for malaria treatment for nearly two thousand years. However, its pharmaceutical mechanism had not been clarified and the specific active ingredient, i.e. Artemisinin, had not been extracted before Tu. Tu drew her inspiration from a Taoist medical classic titled The Handbook of Prescriptions for Emergencies (Zhou hou bei ji fang) written by Taoist priest Ge Hong (283–363) in early medieval China (Miller and Su 2011).

The work by Ge Hong described a mashing method at ordinary temperature, instead of the most frequently used method of high-temperature boiling/decoction in Chinese medicine. This helped Tu’s team figure out the best extracting temperature. Tu was subsequently the first Chinese national to be awarded the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine in 2015 (Zhai, Wang and Li 2016; Fu 2017). Due to China’s long-standing quest for the Nobel Prize (Cao 2014), this event animated the public awareness of the academic contributions by Tu Youyou and also of Ge Hong.

Traditionally, the most famous role of Ge Hong is first of all as a Taoist priest. Ge Hong is most well-known for his Taoist work Baopu zi (The Master who Embraces Simplicity), which is the crystallization of his Taoist ideals and Confucian philosophy. Nonetheless, the second part (“Inner Chapters”) also discusses diseases, elixirs, medicinal chemistry, and nourishing life (yangsheng). In his old age, Ge Hong moved to the Luofu Mountain (Lu fu shan) in southern China, a sacred mountain for Taoist practitioners. In these, Ge Hong focused on elixirs, Chinese alchemy, and medical studies. His activities in southern China are seen as the origin of the Lingnan (literally: the south of the Five Ridges) school of epidemic febrile disease studies (Lingnan wenbing xuepai). Traditionally, the Lingnan area has been best known as a hot zone for epidemics because of its weather and environment. Ge Hong, a Jiangnan-ese born in Jiangsu who then moved further south to Lingnan, had brought along his Taoist medicinal knowledge and became instrumental as one of the pioneers in pre-modern Chinese epidemic studies.

The above-mentioned Handbook of Prescriptions for Emergencies is also notable for its contributions to anti-malarial treatments. This handbook recorded other Chinese herbal medicines for use against malaria, such as Dichroa febrifuga (Changshan). The records of Ge Hong on Dichroa febrifuga might also have enlightened the discovery and development of the anti-malarial drug febrifugine in the 1940s (Lei 1999; Lei 2014: 193–222).

Figure 1 Tu Youyou wins Nobel medicine prize for anti-malaria drug discovery helped by the works of Taoist Priest Ge Hong (Figure Source: Nobel Foundation)

Anti-COVID-19 Drugs and the ‘Huang–Lao’ School

Figure 2. The Inner Canon of the Yellow Emperor (Huangdi nei jing) (Source: Wechat Account Shan ben gu ji)

Recently, the coronavirus has driven people to turn their attention to Taoist medicine again. In pandemic China, there are implicitly Taoist references in naming COVID hospitals (Stanley-Baker 2020). Specific to drug discovery, a team from the Beijing University of Chinese Medicine summarizes the potential anti-COVID applications of formulas and herbs found in the Inner Canon of the Yellow Emperor (Huangdi nei jing), a medical classic following the ‘Huang–Lao’ thoughts (Luo et al. 2020) compiled over 2,200 years ago during the Warring States period (475-221 BC). These herbs include Radix astragali (Huangqi), Radix glycyrrhizae (Gancao), Radix saposhnikoviae (Fangfeng), Rhizoma Atractylodis Macrocephalae (Baizhu), Lonicerae Japonicae Flos (Jinyinhua), and Fructus forsythia (Lianqiao). Currently, the most successful cases are known as SYSF: this stands for San yao san fang, three herbal formulas and three Chinese patent medicines, which have been approved by China’s National Medical Products Administration (previously known as the Chinese Food and Drug Administration) between 2020 and 2021 (Figure 3).

Figure 3. Anti-COVID Drugs Based on (Traditional) Chinese Medicine (Source: Jianan Huang)

Traditionally, the Inner Canon of the Yellow Emperor is regarded as the earliest Chinese work in terms of plague and epidemic studies, even if this argument does not consider newly excavated materials. This classic of the Chinese medical canon presents a systematic record of anti-epidemic herbs and potential preventive measures. This extensive literature enables contemporary scholars towards the drug discovery based on Taoist/Chinese medicine. This means much more than a common paradigm of drug discovery based on natural medicine.

Another team led by Yung-Chi Cheng at Yale University has a long-standing interest in unlocking the potential of ancient Chinese medicine for contemporary medical therapies. Specific to the COVID-19 pandemic, in 2021 Wu et al. have summarized all the applications of Chinese herbal medicines from ancient records , especially from the Treatise on Cold Diseases and Miscellaneous Diseases (Shanghan zabing lun) and the Treatise on Differentiation and Treatment of Seasonal Warm Diseases (Wen bing tiao bian) (Wu et al. 2021). However, while the valuable legacies of ancient Chinese medicine have been stressed, the specific legacies of Taoist medicine remain un-clarified. In fact, a number of beneficial formulas were recorded or even directly developed by Taoist medical scholars, who played pivotal roles in epidemic studies in ancient China.

Final Thoughts

The cases above inspire us to re-think the traditions of health, disease, and medicine in the Taoist culture. The philosophy of Taoism emphasizes the balance among three principles, i.e. jing (“essence”), qi (“vital breath”), and shen (“spirit”). This can be interpreted as a life/health philosophy aimed at longevity, individual well-being, and nourishing life (yang sheng). Taoist ideas of “yang sheng” and the quest for immortality are an integral part of its philosophy.

The application of Taoist works in the field of anti-pandemic drug discoveries proves once again the connection between Taoist tradition and healthcare practice. From malaria to COVID-19, the medical writings by ancient Taoist scholars have been proved valuable for inspiring contemporary pharmaceutical research. With that in mind, it may be helpful to reiterate the need to bring in “alternative” ideas in the understanding of the pandemic and the human body.

References

Cao, Cong, “The Universal Values of Science and China’s Nobel Prize Pursuit,” Minerva, 52 (2014): 141–160.

Fu, Jia-Chen, “Artemisinin and Chinese Medicine as Tu Science,” Endeavour: A Quarterly International Journal Dedicated to the History and Philosophy of Science, 40.3 (2017): 127–135.

Ho, Peng Yoke, Explorations in Daoism: Medicine and Alchemy in Literature, New York: Routledge, 2007.

Kushner, Howard I., “History as a Medical Tool,” The Lancet, 371.9612 (2008): 552-553.

Lei, Sean Hsiang-lin, “From Changshan to a New Anti-malarial Drug: Re-networking Chinese Drugs and Excluding Traditional Doctors,” Social Studies of Science, 29.3 (1999): 323–358.

Lei, Sean Hsiang-lin, Neither Donkey nor Horse: Medicine in the Struggle over China’s Modernity, Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2014, pp. 193–222.

Luo, Hui, et al., “Can Chinese Medicine be Used for Prevention of Corona Virus Disease 2019 (COVID-19)? A Review of Historical Classics, Research Evidence and Current Prevention Programs,” Chinese Journal of Integrative Medicine 26.4 (2020): 243–250.

Miller, Louis H. and Su, Xinzhuan, “Artemisinin: Discovery from the Chinese Herbal Garden,” Cell, 146.6 (2011): 855–858.

Stanley-Baker, Michael. 2020. "Daoism and Disease in China and Diaspora." Hot Spots, Fieldsights, June 23. https://culanth.org/fieldsights/daoism-and-disease-in-china-and-diaspora.

Unschuld, Paul Ulrich, Medical Ethics in Imperial China: A study in Historical Anthropology. Berkeley and Los Angeles: University of California Press, 1979.

Wu, Jieya, et al., “Evolution of Chinese Medicine to Treat COVID-19 Patients in China,” Frontiers in Pharmacology 11 (2021): 2366.

Zhai, Xiao, Qijin Wang, and Ming Li. “Tu Youyou’s Nobel Prize and the Academic Evaluation System in China,” The Lancet 387.10029 (2016): 1722.

Zhou, Feifei. “Traditional Knowledge, Science and China’s Pride: How a TCM Social Media Account Legitimizes TCM Treatment of Covid-19,” Social Semiotics May (2021): 1-17.

Disclaimer: The views and opinions expressed in this article are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the position of the blog editorial team or the Asia Research Institute.

South Asia | Southeast Asia | East Asia | Other Places | Hinduism | Buddhism | Islam | Christianity | Other Religions

Jianan Huang (Jhuang067@t.ntu.edu.sg) is currently a postgraduate student at Nanyang Technological University and previously got his pharmaceutical degree from Zhejiang University. His interests include STS and Asian Studies, with research outputs appearing on Acta Orientalia Hung and Medical History.