Ladles, Flowers, and Rubber Ducks: Pandemic Leftovers at Shinto Shrines in Japan

contributed by Kaitlyn Ugoretz, 7 April 2025

In late February 2020, I visited Yasaka Shrine in Kyoto, one of Japan’s oldest Shinto shrines. At the time, COVID-19 was becoming a global concern, and most Japanese citizens were masking voluntarily and using hand sanitizer more frequently, as they often do during periods of greater risk of infection from viruses such as the common flu. Even prior to the WHO’s announcement that the virus had risen to the level of a pandemic, the threat of COVID-19 was already having clear effects on many aspects of life in Japan, including religious practices.

As I had done countless times before, I made my way through the crowds of visitors to the water fountain near the entrance (called a temizuya or chōzuya) to purify myself. The ritual management of purity and pollution is central to Shinto, and when visiting a Shinto shrine, one must purify oneself before approaching the enshrined deities in prayer. The ritual routine thus begins with a visit to the purification fountain (called a temizuya or chōzuya) to rinse one’s hands and mouth before, a practice called temizu 手水 (literally “hand-water”). It is typical to use one of the wooden ladles sitting on or beside the fountain to scoop up water, pour it over your hands, touch the water to your lips, and tip the remainder over the ladle’s handle to purify it for the next user. At Yasaka Shrine, I was shocked to see that the wooden ladles typically available for use had disappeared from the fountain, and the water source was shut off.

Figure 1. Photo of author practicing temizu at a shrine in Ise, Japan, February 2020 (Source: author).

Figure 1. Photo of author practicing temizu at a shrine in Ise, Japan, February 2020 (Source: author).

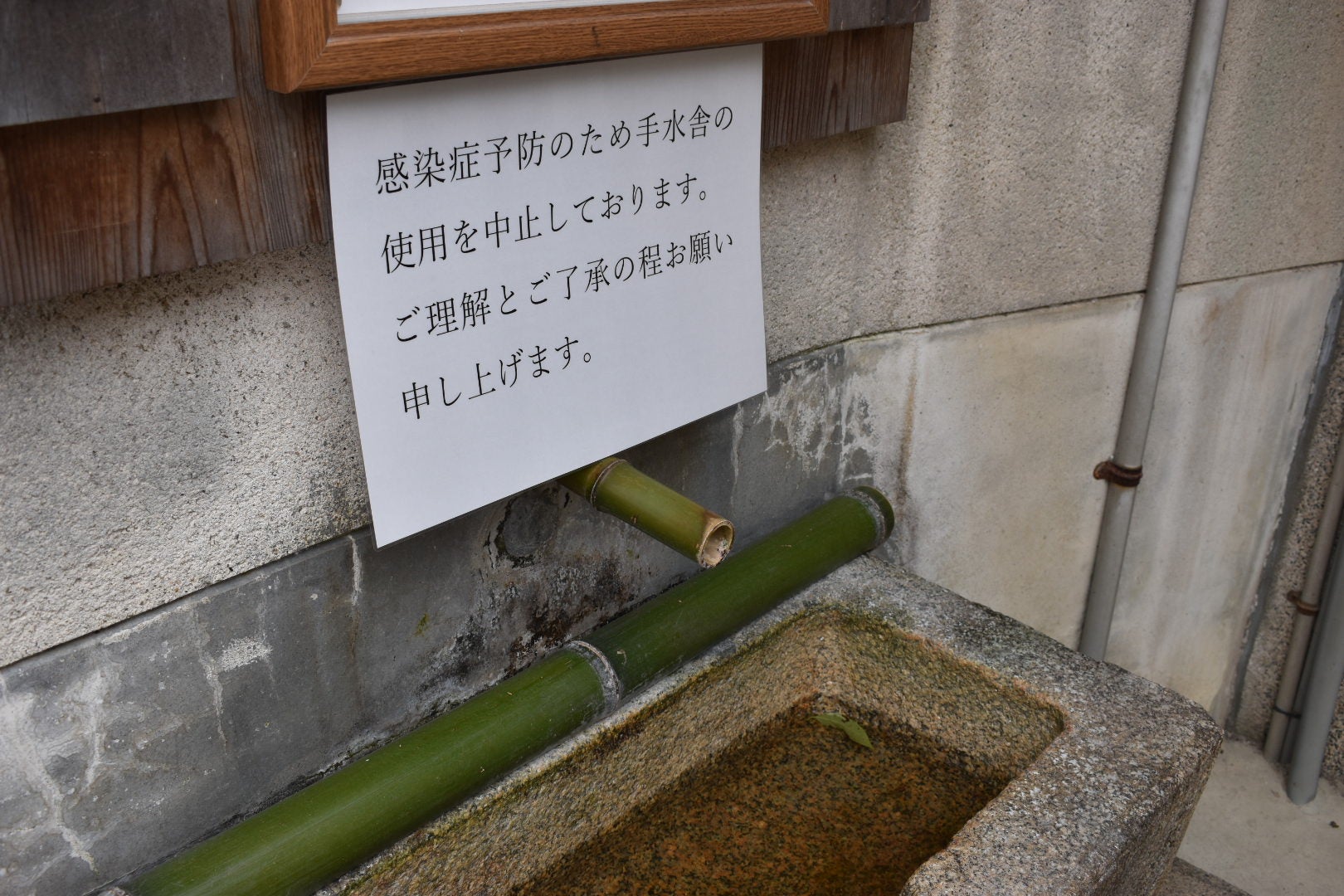

Figure 2. Photo of a sign warning against using a purification fountain, which is turned off and missing ladles, due to the risk of COVID-19 infection. Yasaka Shrine, February 28, 2020 (Source: author).

Figure 2. Photo of a sign warning against using a purification fountain, which is turned off and missing ladles, due to the risk of COVID-19 infection. Yasaka Shrine, February 28, 2020 (Source: author).

I stood in front of the empty fountain at a loss. In the preceding years, I had never been in a situation in which I could not perform temizu. Participation in Shinto ritual is open to anyone, so although I am not what we could call a “practitioner” or “adherent” (these labels do not make much sense for Shinto in general), I have—as an anthropologist who visits shrines often—internalized Shinto etiquette over time as part of my “habitus,” as sociologist Pierre Bourdieu would call it. It felt strange to skip this step, and I considered whether it was inappropriate to approach the gods without having purified myself and if I should just turn around and go home. I wasn’t alone in this feeling, as the topic frequently came up in the news and on social media in Japan. In the end, the resident priests assured me that hand sanitizer was sufficient and that the gods would understand why I could not observe the usual rituals.

It wasn’t long after I returned to the US that Japan closed its borders. However, as an anthropologist interested in digital technology and social media, I kept following from afar how Shinto shrines in Japan were dealing with the sudden problem of ritual handwashing as a vector for disease. And, since moving to Japan for work in 2023 once the border reopened, I have paid attention to what remnants of the Shinto ritual adaptations made during Japan’s period of “[living] with COVID” (uizu Korona) persist “after COVID” (afutā Korona).

Sanitizing the Sacred

The irony was not lost on me that at a time when international health experts promoted handwashing as a method of disease prevention, Shinto ritual handwashing became a potential source of infection. The main concern with the performance of ritual ablutions was that the ladles traditionally used presented a “high-touch” or “high-contact” surface which could facilitate the spread of COVID-19 amongst users.

As a further irony, Yasaka Shrine is famous for its ritual role in protecting against epidemics. The shrine’s summer festival, the Gion Matsuri, features a grand series of rituals and parades designed to protect the local community from the ravages of epidemics held for over one thousand years. In 2020, the public portions of the festival were canceled for fear that the gathering could become a super-spreader event.

Discrepancies between understandings of hygiene and ritual purity highlight the significance of the framework that the authors of CoronAsur refer to as the “sanitized sacred.” The sanitization of the sacred is a process that involves the mediation of religion in response to social constructions of hygiene and virality and institutional prescriptions for disease prevention such as social distancing.

The CoronAsur editors urge us to consider how “Asian religions under pandemic circumstances have reshaped their mediations along the dialectics of dispensation and compensation, hinging upon mimesis and anticipation” (Hertzman et al. 2023, 24) In some cases, religious communities compensated for obstacles to embodied practices in shared physical spaces created by the pandemic by adapting their practices in ways that echo pre-pandemic traditions. In other cases, religious leaders granted dispensation for practitioners to forgo certain rules and rituals due to the extraordinary circumstances in anticipation that regular practice will resume in the future.

As for temizu at Shinto shrines, in the first months of the pandemic most shrines ‘sanitized the sacred’ by opting for dispensation, choosing to simply remove the ladles and turn off the water supply to the purification font. The sight of the empty or off-limits font weighed heavily on the hearts of visitors and encouraged shrines to think creatively about how to utilize the space to bring comfort to their parishioners and allow for some mediated practice of ritual handwashing.

Beautifying Absence

One creative solution that shrines embraced was to fill the temizu basin with cut flowers that float on the surface of the water. This trend, called hanachōzu, evokes an ancient practice of purifying one’s hands with dew collected from flowers and leaves in the absence of water. Although floating flower displays gained limited attention around 2017, hanachōzu skyrocketed in popularity in 2020; it provided both a practical and aesthetic solution to the problem of purification fountains, as the flowers filled the basin in a way that discouraged its use while adding a sense of vibrancy and vitality to replace feelings of emptiness and stagnancy. A bonus was the rise in visitors (and with them, donations) who saw pictures of the colorful flower arrangements on social media platforms such as Instagram and traveled to the shrines (and Buddhist temples) to see for themselves. Goō Shrine and Awata Shrine in Kyoto put a unique spin on the trend by filling their respective fountains with boar figurines (a sacred animal) and rubber ducks (just for fun). The displays have become so popular that many shrines and temples continue to feature seasonal and holiday arrangements, with one shrine in Hokkaido even selecting flowers in certain colors to promote a visiting boyband.

Figure 3. Photo of Goō Shrine’s purification fountain filled with colorful boar figurines, August 2023 (Source: author).

Figure 3. Photo of Goō Shrine’s purification fountain filled with colorful boar figurines, August 2023 (Source: author).

Figure 4. Photo of Awata Shrine’s purification fountain filled with flowers and rubber ducks, 2021 (Source: DragonOne, PhotoAC)

Figure 4. Photo of Awata Shrine’s purification fountain filled with flowers and rubber ducks, 2021 (Source: DragonOne, PhotoAC)

Personalizing Ritual

As the pandemic stretched on, visitors continued to comment that it felt inappropriate to skip the step of temizu before praying or that they missed the ritual aspect of it (in comparison with simply using hand sanitizer), and shrines sought other solutions. The Association of Shinto Shrines (Jinja Honchō) suggested that ladles could be shared if each user disinfected their hands before and after touching the handle, but this solution requires a high degree of effort and supervision.

During this time, there was also a movement to preserve the material culture of using wooden ladles for purification through privatization. Several organizations promoted a “My Ladle” (mai hishaku) campaign which encouraged shrinegoers to purchase and carry their own ladles for personal use. By August 2020, the Ise Grand Shrine Worshippers’ Association began to sell ladles made from scraps of cypress wood leftover from the Ise shrines’ regular shrine reconstruction ritual at their physical and online stores. The association’s website contextualized the practice of carrying a personal ladle within the long history of Ise pilgrimage, noting that doing so identified an individual as a pilgrim deserving of aid from those around them.

Figure 5. Detail from Utagawa Hiroshige’s (1855) Ise sangū miyagawa no watashi (伊勢参宮・宮川の渡し), woodblock print.

Several manufacturing and supply companies noted that ladles had disappeared at shrines during the pandemic and presented personal ladles as a popular solution. In November 2020, Tōmiya launched their ladle line on the crowdfunding platform Makuake and eventually collected millions of yen from hundreds of supporters. Tomiya acknowledged it as a continuation of historical tradition and suggested that it would be a “heartbreaking” loss of an important element of traditional Japanese culture if people were unable to practice temizu at shrines and temples. Their marketing emphasized that their product was part of a “new style of worship” emerging in response to the pandemic. Another selling point was the design itself, which is less than half the size of a typical ladle and features a decorative wrist strap and handy drawstring pouch. Kamidana no Sato marketed their ladles as enabling customers to “enter the shrines where you haven’t worshiped in a while” and “once again face the gods directly as desired.” They also claimed that the ladles would become part of a “new normal” for shrine and temple visits. Their design added a small bell, further suggesting that even if the ladles and bell ropes have been removed by shrine staff, the visitor can continue to participate in traditional forms of veneration by taking matters into their own hands. Customers remarked that they looked forward to being able to perform temizu regardless of whether shrines and temples had removed their ladles and expected that a personal ladle would continue to be an indispensable item even after the pandemic ended.

However, the My Ladle campaign failed to gain popularity and quickly fizzled out. According to surveys conducted by NEXER Inc. in 2020 and 2021, the overwhelming majority of people who planned to celebrate Hatsumōde, the first shrine visit of the new year, would not bring a personal ladle with them. Respondents gave various reasons such as “I’ve never even heard of bringing your own ladle;” “Bringing your own ladle is not popular in my area;” “It’s a hassle;” and “It’s not needed at the shrine.” Shrines largely took steps that obviated the need to purchase and carry one’s own ladle or, in the case of shrines that turned off the water supply to the purification fonts, did not enable those who brought a ladle to use it. Thus, despite the positive press and successful fundraising, My Ladle represents one ritual personalization trend that achieved neither widespread adoption nor long-term success.

Figure 6. Promotional photo of a child using a personal ladle at a Shinto shrine (Source: Tomiya).

Figure 6. Promotional photo of a child using a personal ladle at a Shinto shrine (Source: Tomiya).

Figure 7. Photo of Tomiya Honten’s Mai Hishaku line in several colors (Source: Tomiya).

Constructing a New Normal

Rather than dispense with temizu entirely or expect visitors to come up with their own solutions, many shrines searched for ways to augment their purification fountains using touchless technology to remove the need for ladles.

Some approaches were quite simple and required no digital technology or permanent changes to shrine architecture. Shrines including Ise Grand Shrine and Atsuta Shrine in Nagoya created ad hoc temizu fountains by drilling holes into a large bamboo tube fed by a hose (Figure 8), while others used bamboo poles (or plastic tubing made to look like bamboo) to redirect the flow of water from the spout of the preexisting fountain outside of the basin. These temporary measures reflect the shrine’s anticipation that visitors would be able to return to practicing temizu in a more traditional manner in the near future.

Figure 8. Photo of a temporary purification fountain made by drilling holes in a bamboo tube at Atsuta Shrine, April 2023 (Source: author).

Figure 8. Photo of a temporary purification fountain made by drilling holes in a bamboo tube at Atsuta Shrine, April 2023 (Source: author).

Other shrines went to great expense to install electronic touchless fonts that operate via motion sensors. Designs range from rustic and charming—nearly indistinguishable from analog bamboo fonts—to modern and elegant, using metal, granite, and plastic. In the latter category, shrines like Owari Taga Shrine in Aichi Prefecture preferred a design that mimics the appearance of traditional bamboo taps, while shrines such as Miyajidake Shrine in Fukuoka Prefecture favored bold, unconventional designs, including a five-foot-tall acrylic “aqua panel” that evokes the image of a waterfall.

Figure 9. Photo of Miyajidake Shrine’s aqua panel purification fountain, 2022 (Source: Visit Fukuoka).

Figure 9. Photo of Miyajidake Shrine’s aqua panel purification fountain, 2022 (Source: Visit Fukuoka).

Conclusion

Shinto shrines in Japan have largely returned to their regular activities since the official end of the COVID-19 pandemic in 2023. Surveys of New Years visits at major shrines in 2023 and 2024 show that numbers have rebounded significantly since 2021, although they tend to remain below pre-pandemic records. The remnants of the sanitization of the Shinto sacred linger. The case of the disappearing ladles is one tangible example. While ladles have in large part returned to shrines’ purification fountains, the consequences of their long absence can still be felt.

In 2025, I still find shrines in which the ladles are missing and there are no alternative methods for practicing temizu. The hanachōzu social media trend made such a splash that many shrines and temples have continued to advertise arrangements displayed on special occasions after the official end of the pandemic. As for personal ladles, we can imagine that most now sit on shelves or in cupboards collecting dust, a material reminder of the time when shrine ladles suddenly disappeared. Though analog bamboo fountains were crafted as a temporary social distancing measure, they sometimes reappear from storage during periods when the number of visitors to the shrine spikes. The building of new and redesigned purification fountains represents more permanent material changes to shrine architecture and worshippers’ religious practice, as they removed the need for ladles altogether.

An awareness of the presence, or absence, of ladles is part of Shinto’s post-pandemic “new normal.” I am glad to see that the ladles have reappeared on many shrine grounds. And yet, I can’t quite shake the worry that the potential viral pollution by invisible germs may linger on these high-touch instruments of ritual purification. And when the ladles are missing and no other options for temizu are available, I notice the loss of this embodied practice and still feel somewhat rude in approaching the shrine. Reactions in Japan vary. Some approve of the changes, like touchless temizu, and hope they will continue as a new—even fun—form of shrine etiquette; other interlocutors want things to go back to ‘normal’ as much as possible and to preserve Shinto traditions. That the shrine ladle, something once so innocuous, is an ongoing cause for spiritual and medical concern is certainly a pandemic leftover. With the likelihood of pandemic outbreaks increasing, it remains to be seen whether, and how, things like shrine ladles and practices like temizu will survive.

Figure 10. Photo of author conducting temizu on behalf of shrine visitors at Shusse Inari Shrine of America in Los Angeles, CA, November 2022.

Figure 10. Photo of author conducting temizu on behalf of shrine visitors at Shusse Inari Shrine of America in Los Angeles, CA, November 2022.

Disclaimer: The views and opinions expressed in this article are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the position of the blog editorial team or the Asia Research Institute.

South Asia | Southeast Asia | East Asia | Other Places | Hinduism | Buddhism | Islam | Christianity | Other Religions | Pandemic Leftovers | All Posts

Dr. Kaitlyn Ugoretz is a Lecturer and Associate Editor of Publications at the Nanzan Institute for Religion and Culture in Nagoya, Japan. She received her BA/MA from the University of Pennsylvania and her PhD from the University of California, Santa Barbara. Ugoretz is an anthropologist of Japanese religion and culture interested in the interplay between digital and material culture, popular media, and the environment. Her work mainly focuses on the globalization of the Japanese religion called Shinto, particularly the growth of transnational digital Shinto communities on social media. In addition, as Ugoretz conducted the bulk of her dissertation research during the global COVID-19 pandemic, she continues to investigate the impact of the pandemic on Shinto. Ugoretz is the Japanese Religions Editor for the Database of Religious History, a founding editor of the GAMING+ Project, and the host of the award-winning YouTube channel Eat Pray Anime