Post-Pandemic Social Media as a Site of Prayer

contributed by Rebekah Schultz, 22 May 2025

In the wake of a global pandemic which forced isolation and alternative ways of communicating, social media has become a site for sharing art, liturgies, and prayers with and for one another. Artists and writers who began sharing their work during the COVID-19 pandemic reached an audience across the world and built platforms which still address the needs of their communities today. The communal desire for meaning, beauty, and sacred words heightened by the lack of access to physical worship spaces remains a desire for many who continue to receive and share prayers with others through social media.

This article takes three case studies of U.S. based Instagram accounts which gained popularity as they responded to the pandemic with words and images of hope, beauty, and care. Though @blackliturgies and @enfleshed both grew out of Christian contexts, their liturgies, prayers, and poems are designed for a wider audience not specific to any one religion. While the third account, @houseplantsoftheresistance, shares digital illustrations focused on social justice rather than religion, I argue that this art does not need to be explicitly religious in order to be read and received as prayer.

Based in a Christian context, this article considers prayer broadly as a response to the world around us and a voicing of the hopes, dreams, and liberation one desires for their community as demonstrated through words, images, or actions. After researching these accounts and how they are received by their audiences (through published interviews with the authors, the comments or sharing of posts, and the use of these liturgies in worship spaces), I will consider the ways that post-pandemic social media continues to serve as a method of sharing prayers with and for one another.

Black Liturgies

New York Times bestselling author Cole Arthur Riley created her Instagram account @blackliturgies in June 2020, after the murder of George Floyd in the United States. Riley started the practice of sharing her poems, prayers, and liturgies, as well as quotes from influential Black authors and activists, as a way to center Black voices in the wake of yet more police brutality and anti-Blackness. She describes @blackliturgies as “a space that integrates spiritual practice with Black emotion, Black literature, and the Black body.” With prayers to the God of Black people killed by police brutality in 2020: Ahmaud Arbery, Breonna Taylor, and George Floyd; liturgies for a pandemic, for the anxious, and for the chronically ill; breath prayers; and poems to little Black girls; the account quickly soared in popularity and has continued to rise to its current 566,000 followers. Now, thousands of churches, nonprofits, and individuals turn to Riley’s work as she continues to respond to social justice issues.

Her powerful use of words to process emotions and evoke response resonates with her viewers as she uses her poetic art to bring attention and awareness to various issues. Taking advantage of Instagram’s visual format, Riley is able to share her words with a rapidly expanding audience who, by sharing her posts on their stories or social feeds, spread her work further to their networks.

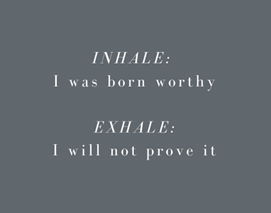

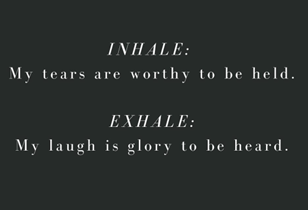

Figures 1 and 2. Cole Arthur Riley, @BlackLiturgies, digital images, Instagram.

https://www.instagram.com/blackliturgies/

Riley’s breath prayers ground a person in their body as an act of embodied liberation and connection with God and oneself. A breath prayer is two short phrases: one to read and repeat in your mind as you inhale and another as you exhale. Her breath prayer “Inhale: I was born worthy. Exhale: I will not prove it” (Figure 1) is a powerful reminder of Black worth and dignity in the face of injustice. Another, “Inhale: My tears are worthy to be held. Exhale: My laugh is glory to be heard” (Figure 2) holds space for lament and joy, honoring the mix of emotions within Black experience.

In these liturgies, prayers, and poems, Cole Arthur Riley has created a space of communal mourning and celebration, protest and prayer. Through social media she has impacted thousands of people and given them words for their struggles and wonder. Riley’s very practice of sharing her words is an act of prayer itself as she puts her hopes, desires, and prayers for her community into writing alongside honest doubt and, in posting these words on Instagram, brings them before God and the world. Prior to the pandemic, sharing of such prayers and liturgies which respond to social justice issues and call for change was not widespread. The isolation of COVID provided grounding for social media to become a site of individual and communal prayer, as words like Riley’s gained traction and connected people to one another and to the divine. As this and other digital platforms grow, it is clear that the pandemic created space for necessary outpourings of sacred words and calls for action that continue today.

Enfleshed

Enfleshed is a nonprofit organization that provides liturgical resources from an intersectional Queer and racial justice perspective. Their Instagram account @enfleshed gained popularity during the pandemic and has continued to grow since. While enfleshed has its roots in Christian liberation theology, many of their liturgies and poems are written without reference to any specific religion. In an interview, M Jade Kaiser, a co-founder and co-director of enfleshed, stated that “We’re trying to really do the ‘both, and,’ continuing to resource those on the edges of Christianity and also holding the liminal space of resourcing people unrelated to religion or formerly religious who are longing for sacred words.” Through this, enfleshed reaches a broad audience in addition to the approximately 700 churches that use their weekly liturgies in worship services.

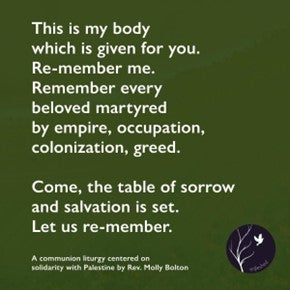

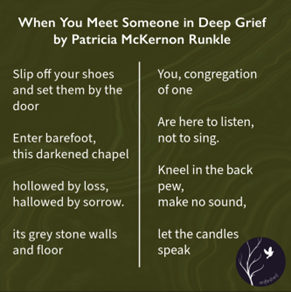

Enfleshed’s liturgies respond to contemporary events such as the COVID pandemic, Black Lives Matter protests, Pride celebrations, anti-trans violence, and the Israel-Palestine conflict. “A communion liturgy centered on solidarity with Palestine” (Figure 3) connects the death of Jesus to the deaths of Palestinians in Gaza today, calling us to remember God’s identification with the oppressed and to work for liberation, justice, and peace. Other liturgies provide responses to grief, laments for harm done, and the importance of interdependence. The liturgy “When You Meet Someone in Deep Grief” (Figure 4) uses religious imagery to describe the sacred loss of grief and how to be present with someone in it.

Figure 3. Molly Bolton, enfleshed, A communion liturgy centered on solidarity with Palestine, March 20, 2024, digital image, Instagram. https://www.instagram.com/p/C4vRcT3Rh_Y/

Figure 4. Patricia McKernon Runkle, enfleshed, When You Meet Someone in Deep Grief, September 30, 2024, digital image, Instagram. https://www.instagram.com/p/DAjFQ6kRN38/

As their liturgies invite “transformation—internal, material, and collective,” enfleshed embodies the intertwining of faith and liberative action they hope to see in the world. Their liturgies effectively address the concerns of their audience, finding sacredness in responding to contemporary events and advocacy. Using the visual format of Instagram, enfleshed structures their posts in appealing and reflective ways precisely to create space for the viewer to pause and reflect on the words of each prayer. Through this concrete practice, I believe that enfleshed prays with and for their community of those at the fringes. Though enfleshed was started in 2017, the pandemic spurred their rise in popularity and allowed them to grow significantly. Since then, enfleshed has continued to build the resources they offer and engage their audience on social media through their liturgies and by asking questions, inviting response, and hosting Instagram lives and Zoom conversations. Precisely because of the pandemic, enfleshed has been able to reach a larger audience and continues to use social media as their vital site of community formation and prayer.

Houseplants of the Resistance

The Instagram account @houseplantsoftheresistance began anonymously in August 2020, featuring digital art of houseplants alongside protest phrases. The creator of the account has stated that “The goal of this project has always been about three things: awareness, giving money back to the causes I'm featuring, and sharing my love of houseplants.” The artist uplifts various social justice causes through including phrases like The Future is Feminist, Amplify Black Voices, Climate Action Now, and No Human Is Illegal. Houseplants of the Resistance also has an Etsy shop where art prints and stickers are available for purchase and proceeds are donated. Each image is designed to support a different organization such as the American Civil Liberties Union, Black Lives Matter, the Trevor Project, etc.

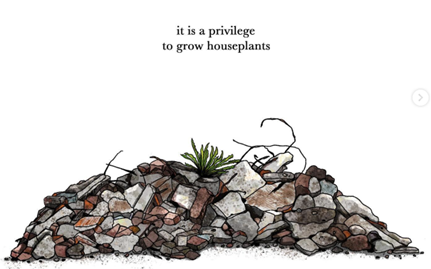

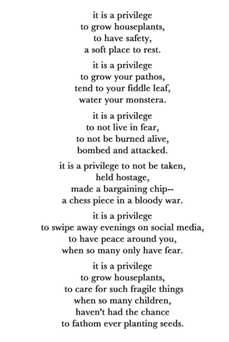

One powerful piece differs from the typical design of a healthy potted houseplant and protest phrase. A small leafy plant rises out of rubble (Figure 5). Broken bricks, stones, and wires lie in a crumbling heap together; above are the words: “it is a privilege to grow houseplants.” Posted on June 1, 2024, this art recognizes the violence of our world, particularly in reference to the Israel-Palestine conflict and the Russia-Ukraine war. The post includes a poem (Figure 6); a portion of which reads:

“it is a privilege

to grow houseplants,

to care for such fragile things

when so many children,

haven’t had the chance

to fathom ever planting seeds.”

As this image and poem name the violence of war and the privilege we have to even see this on social media, I argue that the art acts as a prayer for all those affected by war and also calls us, the viewers, to use our privilege to advocate for others.

Figure 5. Houseplants of the Resistance, Privilege, June 1, 2024, digital image, Instagram. https://www.instagram.com/p/C7rtvaxvKyz/

Figure 6. Houseplants of the Resistance, Privilege Poem, June 1, 2024, digital image, Instagram. https://www.instagram.com/p/C7rtvaxvKyz/

Through these illustrations, @houseplantsoftheresistance brings awareness to contemporary events and social justice causes, calling for change. This art is a prayer as it shares the artist’s own passions and emotions alongside what they hope and advocate for their community to look like. It is a communal prayer as it is shared on social media and spread from one person to another as they recognize their own dreams embodied in each piece. It is a prayer as it calls for response through social change and physical actions. It is a prayer as it causes us to slow down and reflect on our world and who we are in it. As the artwork sold generates funds to be donated to the organizations represented, each piece is a prayer putting actions behind its words.

This account is a prime example of the leftovers of pandemic social media. It did not exist before 2020 when COVID shut down the major infrastructures of our society. Yet, five years later, it remains a strong and vibrant influence on social media, sharing art and prayers with an audience that continues to grow.

Social Media as Sacred Space

In a pandemic in which churches closed their doors and worship services were held online, sacred spaces were no longer in-person but digitally. Though we’ve now returned to in-person events and worship as usual, social media has remained a sacred space where one can encounter the divine through liturgical words, communal prayers, and images of hope. In defiance of the fast-paced momentum of everyday life and the flood of information and images that are accessible on social media, the artwork of these accounts asks us to slow down, to pause and sit with these images. It invites the viewer to read the words of the poems, liturgies, letters, and protest phrases, and to consider the world they describe, creating space for prayer and meditation.

Moreover, this artwork is created in and for community. The art of @blackliturgies, @enfleshed, and @houseplantsoftheresistance recognizes the humanity of the viewer and calls them to see their own value as well as the dignity of others. Such artwork “stares back” at the mindless scroller on Instagram who shifts from one image to the next in the blink of an eye. It catches the viewer’s gaze and holds it, halting the constant scroll and beckoning the audience to consider the meaning of the image and its words. Such work invites the community into this collective viewing and imagining as an act of liberation and an act of prayer. Thus, as a method of sharing information, imaginings, and calls for change, social media has become a foundational site of community building and collective prayer. It has become a sacred space.

Conclusion

One positive outcome of the pandemic was a push toward alternative ways of communicating with one another and of being in community. Now two years out from the official end date of the pandemic (May 11, 2023), many religious organizations continue to livestream worship services and to share prayers on social media. As @blackliturgies, @enfleshed, and @houseplantsoftheresistance all work to bring beauty, justice, and hope into their communities, the art itself becomes a prayer that prompts practical action and change. Each post is a prayer for the world and for the community, a hope for change and a dreaming of what could be. As we rebuild out of the devastation of the pandemic, the sacred sharing of prayers, liturgies, and community on social media are the shoots of new life breaking through the rubble.

Disclaimer: The views and opinions expressed in this article are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the position of the blog editorial team or the Asia Research Institute.

South Asia | Southeast Asia | East Asia | Other Places | Hinduism | Buddhism | Islam | Christianity | Other Religions | Pandemic Leftovers | All Posts

Rebekah Schultz is a Ph.D. student in Religious Studies at the University of Virginia. She has a B.A. in both Theology and Studio Art and an M.T.S. from Duke Divinity School with a certificate in Theology and the Arts. Her research focuses on theology and aesthetics and she is particularly interested in art made during the COVID pandemic. Rebekah loves exploring art as worship, prayer, and sacrament, and she enjoys making art as well as researching and writing about it. Her woodblock prints have been commissioned by Duke University Chapel, published by Artists’ Literacies Institute, and presented at Boston College’s Accessing the Divine conference.