Re-sensorializing Chinese Religion in Singapore?

contributed by Ying Ruo Show, 04 June 2020

Digital Ethnography of Chinese Temples in Singapore amid the COVID-19 Pandemic (Part 2)

The spread of coronavirus in Singapore and the social distancing measures implemented to stop the spread of the virus disrupted the balanced interaction between Chinese temples and their devotees, both socially and economically. Given the constraint of space in Singapore, most religious sites, including Chinese temples, are granted only thirty-year leases. At the end of the lease they have to either pay to renew or purchase a new site from the government, relocate and then build a new temple. “Combined temples” or “joint temples” are a new creation in Singapore in recent years whereby a few temples pool their funds and collectively purchase a plot of land, where they can construct a building to house their deities.

As such, devotees’ donations to temples function not only to please the gods or to praise their efficacies, but also to support the temples for their long term survival. During the circuit breaker, such donations received by temples have decreased significantly as devotees are unable to visit. The same situation applies to smaller Hindu temples in Singapore as their donations dry up during this pandemic.

Technical challenges to set up online donation platforms impact many Chinese temples during this period. Livestreaming services through Facebook, Skype, Zoom and other portals pose great challenges to many administrators of small temples who tend to manage their temples on their own, and cannot afford a tech-savvy support team to help with temple affairs. They often belong to the older generation of Chinese who speak dialects in their daily conversations and have rudimentary English ability.

In addition, certain requirements have to be satisfied if temples decide to go online to livestream their activities during the pandemic. Temple personnel have to first obtain approval from the government (sometime limited time exemption is offered, e.g. for the Vesak Day celebrations). Only 5 people can be allowed to be in the temple premises at a time, and during livestreaming sessions, a maximum of 2 persons are allowed to be on screen, as part of the safe distancing measures.

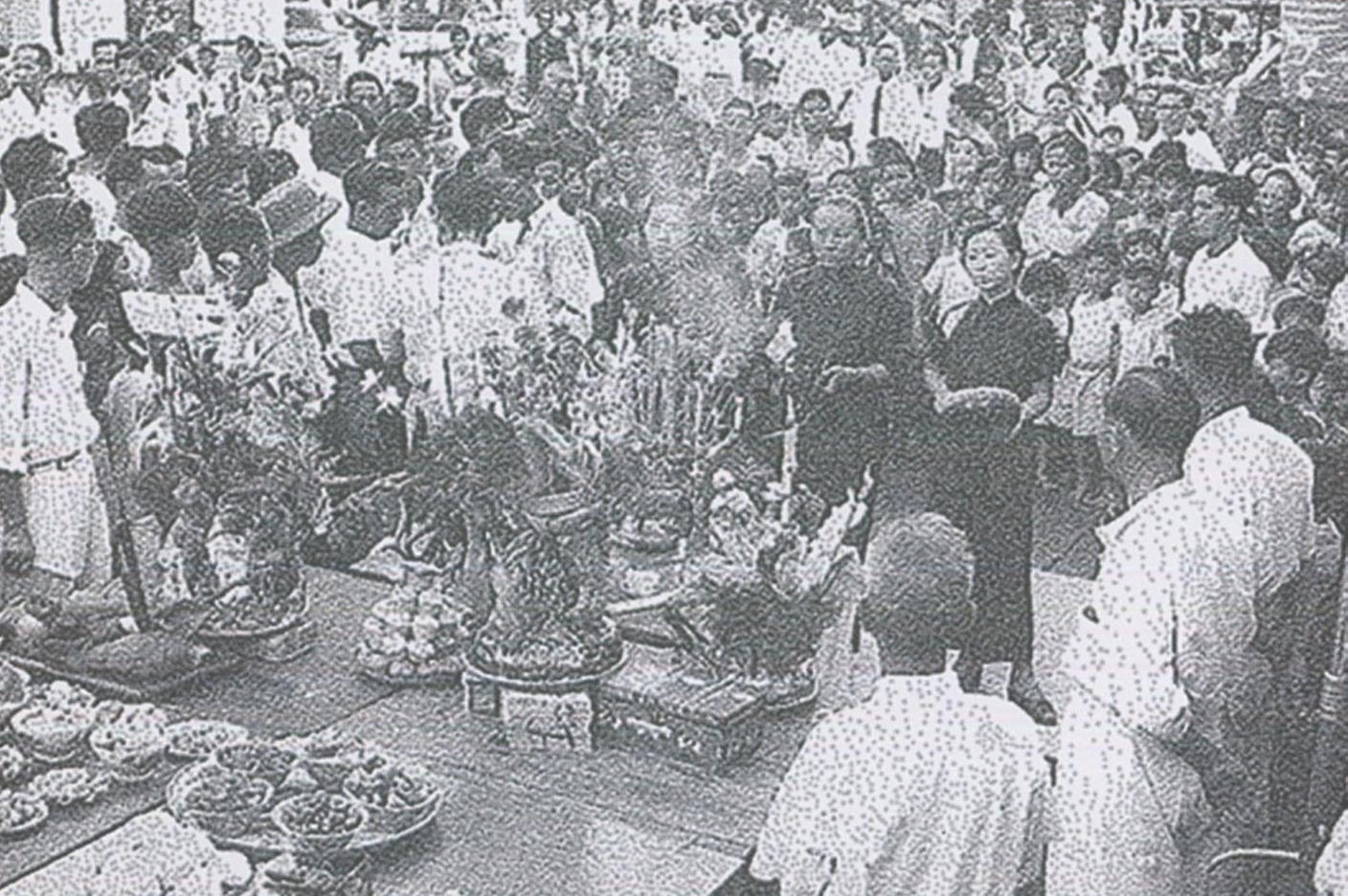

One can go as far to say that the desensorialisation and disembodiment of Chinese traditional culture has been an on-going process in postcolonial Singapore. Rituals are simplified to suit the busy urban lifestyle, and sights and sounds are constantly regulated in a constrained urban space.

Nonetheless, the coronavirus intrusion prompts us to look into the urgency of this matter. With several Chinese temples having their land leases expiring in a year or two, losing several months’ donations is not a small matter. While some established temples, such as the Kong Meng San and Fo Guang Shan, have easy access to technological resources in setting up their online offering platforms, smaller temples or family shrines struggle with limited funds and have no choice but to accept an abrupt temporary separation from their devotees.

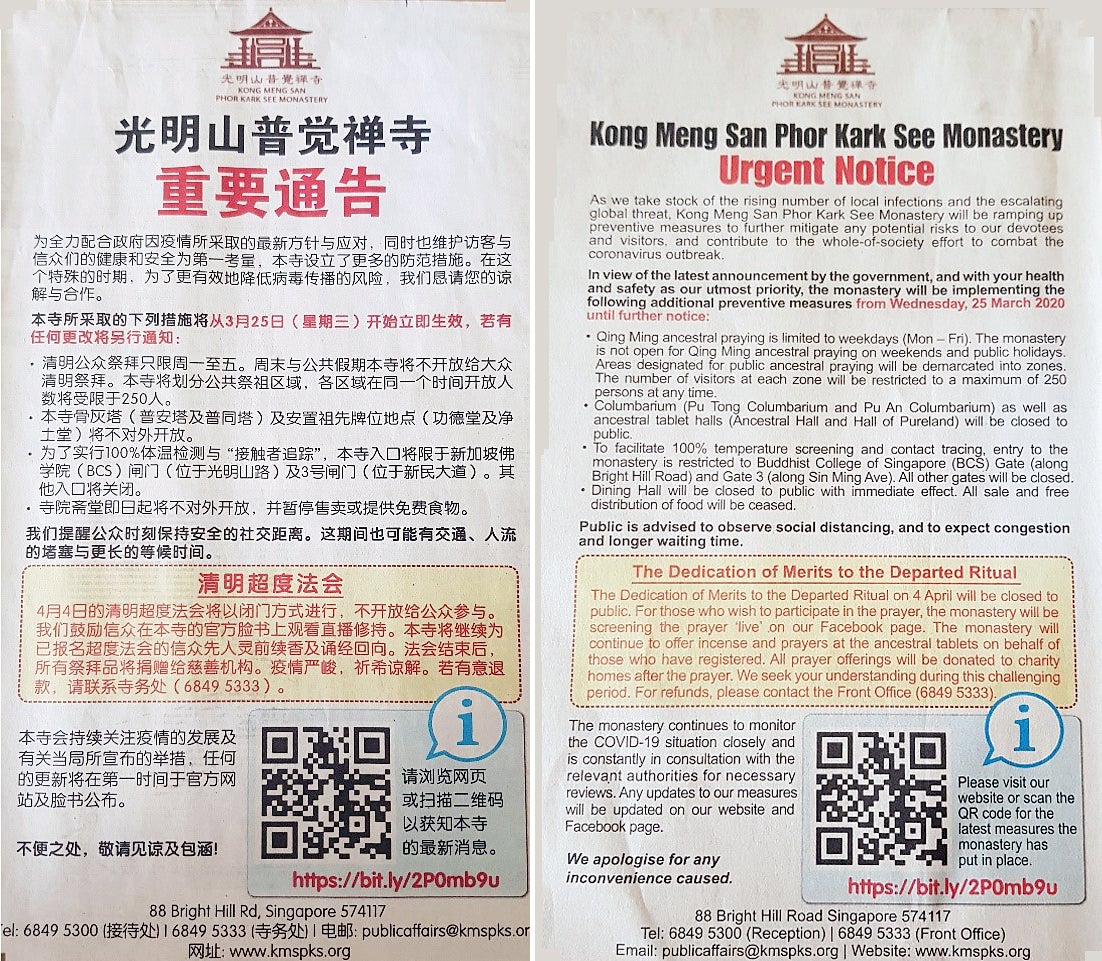

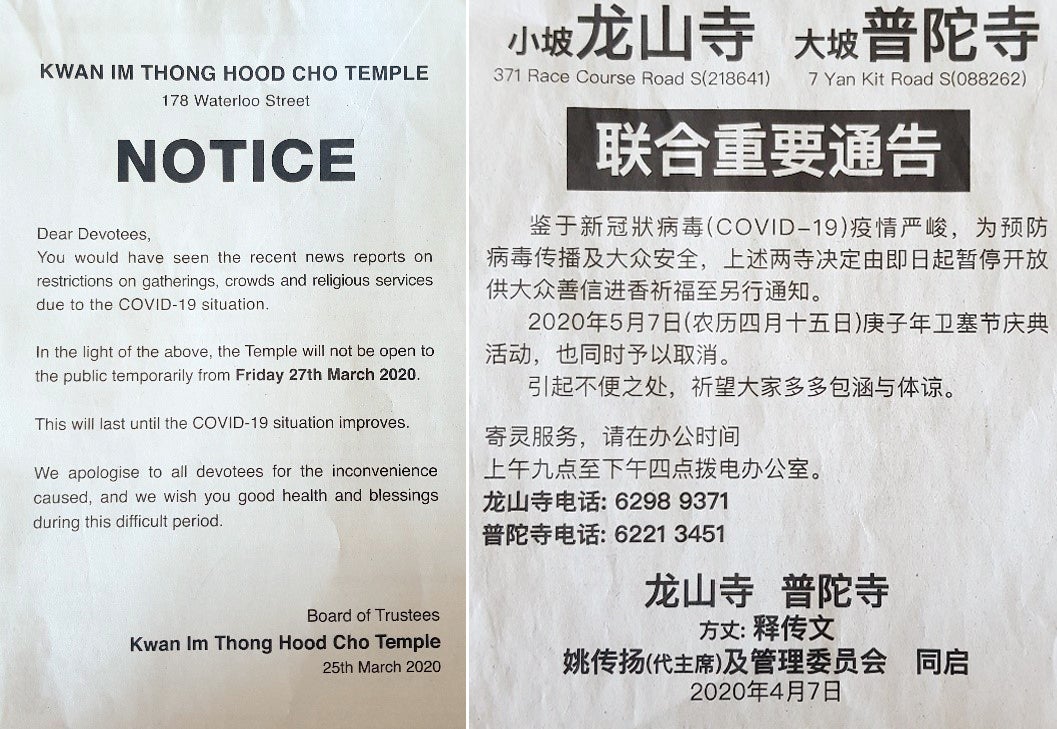

With the cancellation of ritual services and celebratory banquets where fund raising auctions are held, temples are unable to generate income in this period of social restriction. From another perspective, while established temples often have sufficient funds to publish newspaper announcements to inform their devotees about the temples’ situation during this period (sometimes they can even afford to release notices in both the Lianhe Zaobao 聯合早報 and the Straits Times), temples struggling financially in the middle the pandemic cannot afford to do so.

Fig. 1. Chinese notice of Kong Meng San Phor Kark See Monastery published in Lianhe Zaobao, 24 March 2020, 07

Fig. 2. English notice of Kong Meng San Phor Kark See Monastery published in Strait Times, 24 March 2020, A8

Fig. 3. English notice of Kwan Im Thong Hood Cho Temple published in Strait Times, 27 March 2020, B3

Fig. 4. Chinese notice of Leong San See and Poo Thor Jee published in Lianhe Zaobao, 07 April 2020, 07

To seemingly “resensorialise” the situation, one has to take a closer look not only at the uneven distribution of resources in the time of Covid-19 but also at the mutual-constitutive dynamic between religious experiences and people’s sense of community. What religious rituals and practices are performed in the urbanised world of modern Singapore, and what are their functions in the socio-cultural context? What are the differences in the characteristics of the embodied sensation of Chinese ritual activities in the history of early Singapore and today? What has changed, and what has remained significant? How is the human body involved and addressed virtually during the pandemic? What kinds of sensory engagements are bridged through virtual contacts?

Vegetarian nuns performing “Buddhist rites” in early Singapore

(Source: Shi Shansen ed., Bainian shiguang tekan, 1919-2010 百年時光特刊 (A Hundred Years of Flowing Time, 1919-2019: Special Commemoration Issue of the Founding of Shan Fook Tong Temple) (Singapore: Shan Fook Tong, 2019)

Other places-of-worship in Singapore have also been seeking ways to adapt to their new realities. A guide book for the holy month of Ramadan has been launched by the Islamic Religious Council of Singapore (Muis) for Muslims in Singapore, “detailing how they can perform special prayer and practice their faith while doing their part to prevent the spread of the coronavirus.” “Virtual churches” are being established throughout the island for the Christian community. Livestreaming of puja (prayer service) for the Tamil New Year or Puthandu, and other ritual activities have been made possible by Hindu Endowments Board.

These efforts have served to help bind the devotees with their religious spaces and their sense of ethnic community. As a valuable exercise in digital ethnography, we need to carefully study the sensory registers that are invoked during these live streaming and virtual sessions to know whether the new ways to operationalise religion during the pandemic are effective. In the middle of the pandemic, the desensorialisation discourse once again remind us of the close links of people’s mobility, their sense of community, and the religious world view at the micro level, albeit tightly regulated and mediated by the official discourse.

Ying Ruo Show received her PhD in Chinese Studies at the National University of Singapore in 2017. She is currently a Postdoctoral Fellow in the Asia Research Institute at the National University of Singapore. She was Visiting Fellow at the Nalanda-Sriwijaya Centre, ISEAS-Yusof Ishak Institute, and Center for Religious Studies, Ruhr University of Bochum. Her research interests include lay Buddhist narratives, gender and religion, and the history of the Chinese diaspora in Southeast Asia.

Disclaimer: The views and opinions expressed in this article are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the position of the blog editorial team or the Asia Research Institute.

South Asia | Southeast Asia | East Asia | Other Places | Hinduism | Buddhism | Islam | Christianity | Other Religions

Ying Ruo Show

Dr Show received her PhD in Chinese Studies at the National University of Singapore in 2017. She is currently a Postdoctoral Fellow in the Asia Research Institute at the National University of Singapore. She was Visiting Fellow at the Nalanda-Sriwijaya Centre, ISEAS-Yusof Ishak Institute, and Center for Religious Studies, Ruhr University of Bochum. Her research interests include lay Buddhist narratives, gender and religion, and the history of the Chinese diaspora in Southeast Asia.