“Burden us not with that which we have no ability to bear”: cultivating endurance through digital connection in Ramadan

contributed by Yasmeen Arif, 15 July 2020

“Ramadan 2020 will be a very different experience for Muslims all over the world”, acknowledged the Muslim Council of Britain in April 2020. The COVID-19 pandemic and attendant lockdown in the UK prohibited customary observations of Ramadan, forcing the speedy development of alternatives. Recognising that religious practices are shaped by their channels of reception, transmission and mediation (Engelke 2010), this post will trace one particular manifestation of religious discourse within my own kin network – the sharing of pictures, audio and video messages, with specific reflections on how Muslims should understand and respond to the pandemic.

Figure 1. Messages exchanged between my sisters and me at Sehri time, when we were preparing our pre-dawn meals in our separate homes. April 2020

Achieving digital connection during Ramadan

While the circulation of religious imagery and text, both during Ramadan and during the rest of the year, is nothing new (cf Schielke 2012, Rollier 2010), the messages transmitted this Ramadan felt especially poignant. Alongside the existential fear, illness and insecurity caused by the spread of the coronavirus, members of my family also grieved the social experience of Ramadan as a time of communal fasting, prayer and commensality. As households passed the month in isolation, messages circulating via WhatsApp, Telegram and SMS enacted ties of relationship that couldn’t be realised in person.

Figure 2: messages exchanged between my sisters and me before iftar, as we were preparing to break our fast separately. April 2020

Digital connection took many different forms. My sisters and I sent each other pictures of our meals as we prepared iftar separately, and chatted before dawn as we rose for Sehri. I talked regularly to one cousin as the sun dipped low in the sky, both speaking in hoarse voices as we waited for the fast to open. Another cousin told me that “On our sibling group, we shared sermons...and lectures from scholars we follow as well as snippets of ahadith, texts (even memes!) When we next saw each other, we’d weave in bits of what we shared into our discussions and it allowed us to feel that the time away from each other made sitting in each other’s company later on so much more meaningful.”

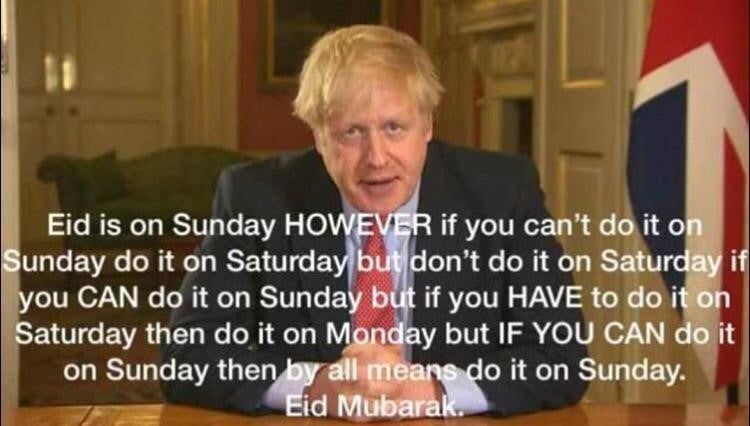

Figure 3. The approach of Eid 2020 coincided with the announcement of the first easing of lockdown conditions in the UK. The confusing and somewhat contradictory governmental guidance was satirised in messages like this one that circulated in a number of group chats, including that of my own family. May 2020

Many of the messages sent and received during Ramadan were ‘forwards’ of images, audio files and videos. Such messages have been theorised as symptomatic of a remarkable individualisation and democratisation of religious knowledge, enabled by the spread of mass technology and communication. Against the painstaking chains of legitimation that characterise the transmission of ahadith, Rollier notes that ‘the issue of authorship, traceability and authority seems absent from Islamic SMSs’ (2010: 419). While I found such forwarded messages rather impersonal, their untraceability rendered them ‘purer’ to a friend of mine. Receiving these messages made her feel that “It’s like they are being sent from Allah ta’ala, directly to me”, suggesting that digital communication might even facilitate connection with the Divine. It was these forwarded messages that I found especially thought-provoking as part of the digital mediation of Ramadan and the pandemic.

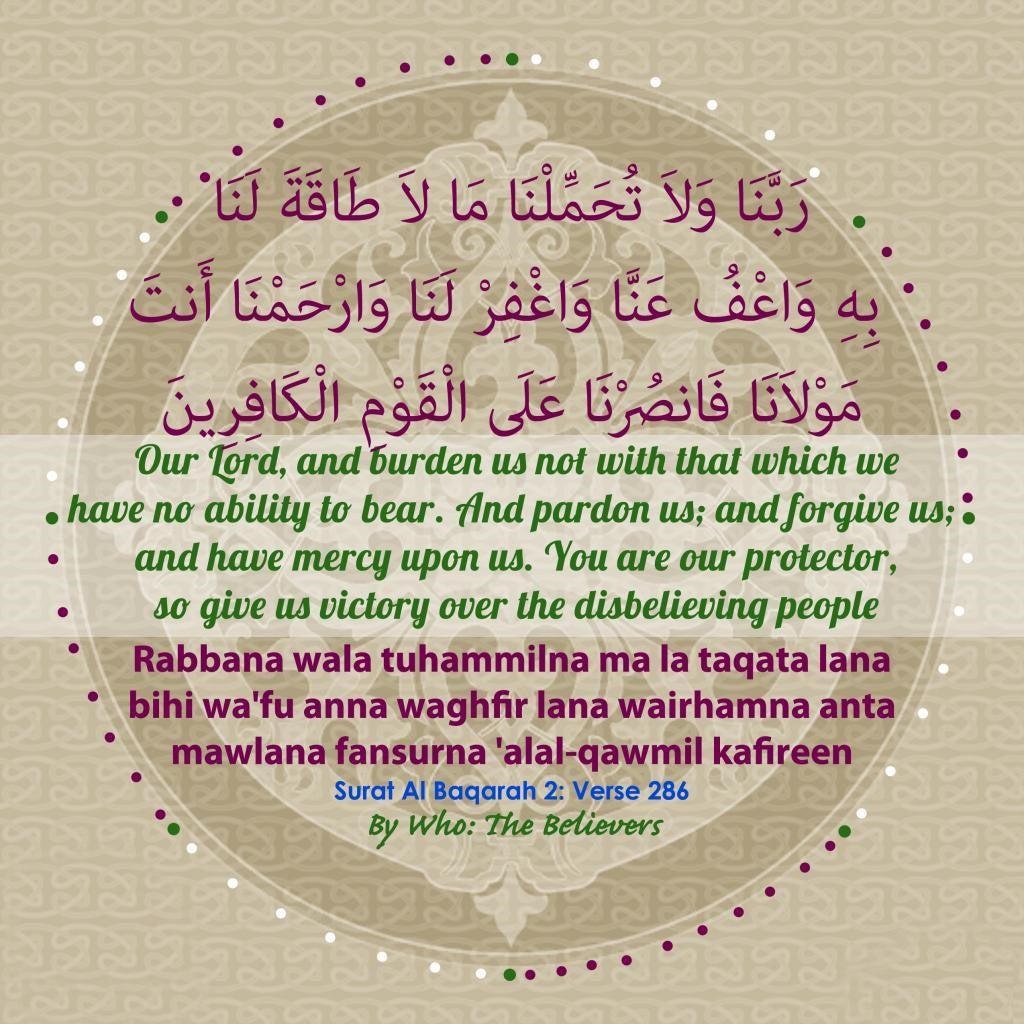

Figure 4. An image forwarded to me on WhatsApp by my cousin. May 2020

“Think of isolation as a blessing”

When reading some messages, I was struck by how timely they felt to the current moment. Many forwards were of Qur’anic ayaat (verses) that acknowledged Allah’s omnipotence and requested His compassion. “Burden us not with that which we have no ability to bear,” read one message, a passage from Surat al Baqarah; in the midst of a deadly pandemic and social isolation, this felt like a deeply necessary plea.

Figure 5. An image forwarded to me on WhatsApp by a cousin. This image had arrived on her phone from a family WhatsApp group. May 2020

Some messages encouraged recipients to utilise lockdown to develop relationships with one’s household, with one’s neighbourhood, and ultimately with God. “When you read the Qur’an, it is Allah speaking to you. When you make dua (pray), it is you speaking to Allah,” lectured a shaykh in one forwarded video. “As you read the Qur’an, convert every ayat into a dua.” Such messages reframed the experience of Ramadan during a pandemic as an opportunity rather than a crisis, a chance to develop one’s faith. “Think of isolation as a blessing”, encouraged one video. “It was in isolation in a cave that the Prophet, salAllahu alaiyhim wasalam (blessings be upon him and peace), received revelation.”

"Know with all certainty that Allah wants to know how you respond"

A theme across many of the messages was the importance of approaching the challenge of observing Ramadan during the pandemic with the required attitudes of patience, endurance and faith. “The barakat of jammah (the blessing of congregation) is no longer available to us in Ramadan 2020...yet as sad as this feels, we can’t let this get us down. We have to minimise our losses...by replicating this jammah in our home…” advised a video produced by the Australian OnePath Network. “Allah is watching; know with all certainty that Allah wants to know how you will respond.”

Virtues of patience and forbearance were positioned as key to the meaningful experience of the pandemic. One message invoked role models of fortitude in the prophets, offering behavioural exemplars to the recipients of the message, and creating an imagined community of shared emotional experience across space and time:

“Allah tests those whom He loves the most!

When you are hurt by people who share the same blood as you,... just remember Prophet Yusuf (pbuh), who was betrayed by his own brothers.

...If you’re stuck with a problem where there’s no way out...remember Prophet Yunus (pbuh), stuck in the belly of a whale.

… If you’re ill your body cries with pain...Remember Prophet Ayub (pbuh) who was more ill than you.

When you can’t see the logic around you...Think of Prophet Noah (pbuh) who built an Ark without questioning...

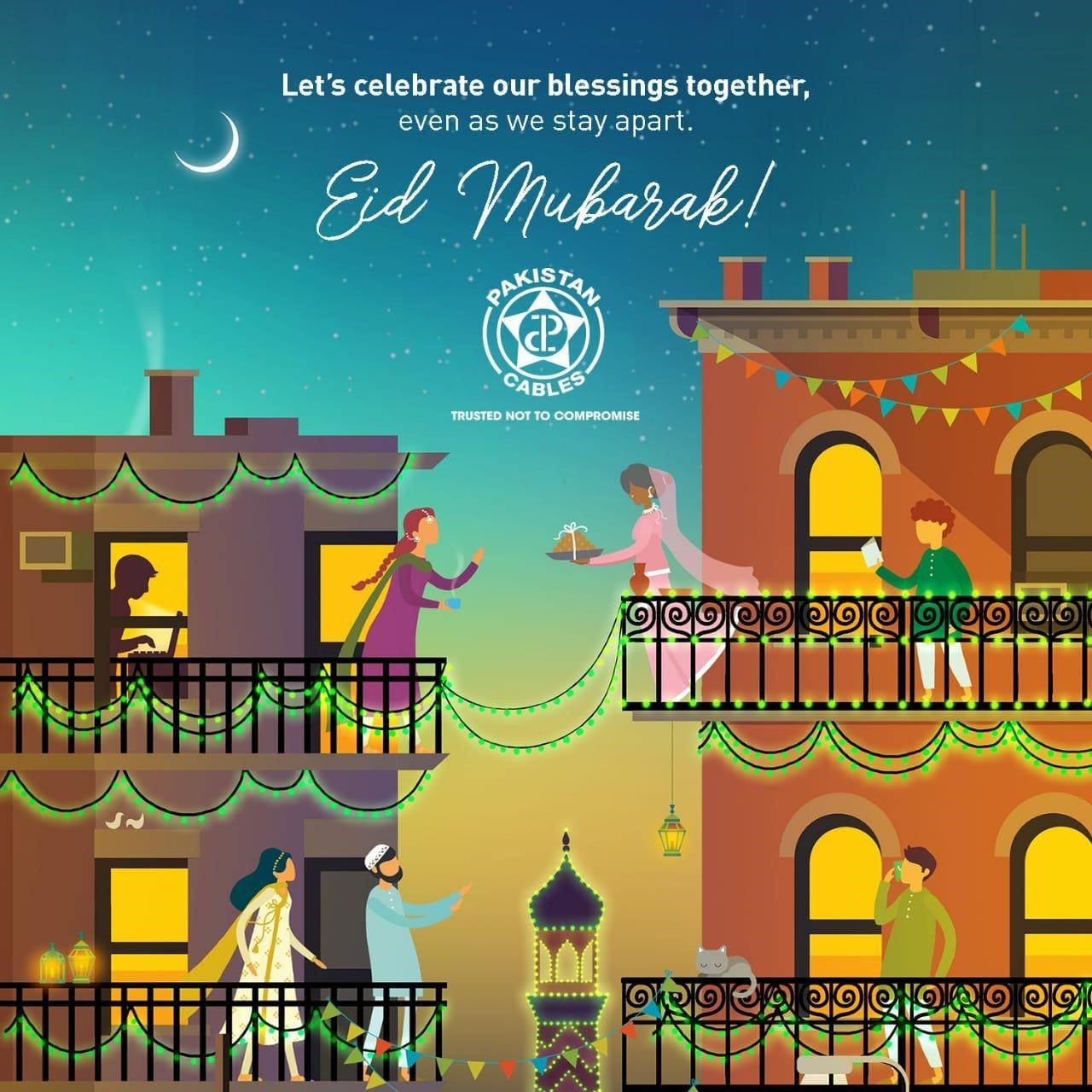

Figure 6. An Eid greeting image that I received from a family group. The message – ‘Let’s celebrate our blessings together, even as we stay apart’ - seemed to strike a chord with many recipients, since this message arrived on my phone several times from different senders. I, too, felt moved by this image, and forwarded it several times. May 2020

Conclusion: when is patience not a virtue?

Meanings attached to the transmission of such messages are likely to vary widely. Rollier notes that Pakistani youths forward messages to express affection, disseminate knowledge and encourage piety, while Schielke suggests that Egyptian forwarders of Facebook messages are motivated by capitalist notions of accruing religious profit (Rollier 2010: 420; Schielke 2012: 139). As difficult as it is to divine motivations for transmission, it is even more difficult to trace how these messages, received in social isolation, are interpreted and understood. Only by pausing the chain of transmission, discussing them with my family and reflecting upon my own, auto-ethnographic response to the messages, could I analytically approach the content of these transmissions.

As I read these messages, I was conscious of conflicting emotional reactions. Some messages made me feel deeply ‘seen’, as if the fear and anxiety I had been living with for some weeks had been recognised and responded to with reassurance. But at the same time, I found some messages problematic in the assumptions they made about Muslim lives. The widely-circulating acknowledgment that Muslims would struggle to achieve a satisfying experience of Ramadan without being able to visit the masjid seemed to posit a male subject whose access to mosques, unlike that of many women and other marginalised groups, had never been contested. Similarly, the injunction to find solace in the family home seemed like idealised heteronormativity, blind to the gendered inequalities of labour and care exacerbated by lockdown.

I also struggled to approach the pandemic and its attendant consequences with the patience extolled in the messages. By May 8th, about halfway through Ramadan, there were already more than 37,000 COVID-19-related deaths in the UK, and growing recognition that such a high mortality rate could have been avoided if the UK government had acted differently. A disproportionate number of the deaths had occurred in Black and minority ethnic communities, with a report published in June identifying systemic racism as a key factor; Black and Brown people were also over-represented among the ‘key workers’ who were applauded from doorsteps every Thursday evening without any corresponding increase in salary or job security. Patience, to me, felt like the most inappropriate response to the pandemic; I felt angry, incapable of the endurance to fast and pray with fortitude. As we moved through the month of Ramadan, another hadith kept coming to my mind:

“If you see an injustice, change it with your hand;

If you cannot do that, speak against it with your tongue;

If you cannot do that, hate it with your heart;

And that is the least of faith.” Hadith 34.

Figure 7. My second-to-youngest sister, the only one of my siblings living at home during Ramadan, carefully painted her own mendhi and photographed it against the summer sky before posting the images on her Instagram account. Sisters usually do each other’s mendhi the night before Eid, on Chant raat (moon night), but this year, we four sisters were all living separately. When I saw these pictures on the day of Eid, they felt surprisingly festive, and I complimented her design when we spoke over FaceTime later that day. May 2020

References:

Engelke, M. (2010). Religion and the media turn: A review essay. American Ethnologist, 37(2), 371-379.

Rollier, P. (2010). Texting Islam: Text messages and religiosity among young Pakistanis. Contemporary South Asia: South Asian Media in the Noughties, 18(4), 413-426.

Schielke, J., & Debevec, L. (2012). Ordinary lives and grand schemes [electronic resource] : An anthropology of everyday religion (EASA series ; v. 18). New York: Berghahn Books.

Yasmeen Arif is a D.Phil candidate in Anthropology at the University of Oxford. Before the pandemic she was carrying out fieldwork in Lahore, Pakistan, on gender, environmentalism and urban change. She is indebted to her family and friends who contributed to this essay, and wants especially to thank Nadia, Tasneem, Ai-sha, Syara, Sana, Nabeelah and Achas, who read multiple drafts, offered comments and reflections, and agreed to their words and images being quoted.

Disclaimer: The views and opinions expressed in this article are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the position of the blog editorial team or the Asia Research Institute.

South Asia | Southeast Asia | East Asia | Other Places | Hinduism | Buddhism | Islam | Christianity | Other Religions