Sites of Worship during the Pandemic – A Pedestrian Photo-essay from the Heartlands

contributed by Chand Somaiah, 31 July 2020

In this photo-essay I curate and collage a visual narrative based on my experiences walking around religious sites in my new-old neighbourhood of Toa Payoh, a prototype Housing Development Board (HDB) town located in central Singapore.

By ‘walking through social research’ (Bates & Rhys-Taylor 2017) and using pedestrian phone-photography, I initially set out to observe eight local sites of worship, from the outside, amidst the current pandemic context in which many of these spaces remain closed. Unexpectedly, however, I chanced upon some other religious sites which, until now, I had not been aware of and which I have included here.

What unfolds is a reimagining of urban, public, performative modes of religion. More ‘mediatization’ (Couldry 2008) through online (social) media occurs by present necessity. I ponder how religion is accessed and consumed as an individual, household and community during the current pandemic context.

I contemplate a forced migration of shared, embodied experiences embedded within brick-and-mortar sacred space into ‘cybergrace’ (Cobb 1998) and attempt a rudimentary visual mapping of this continuum, where these online sites exist.

Defensive and hostile ‘architecture’ of cordon tape and padlocks around sites of spiritual salve, transcendence and inclusion can create cognitive dissonance, a counter-intuitive affront. Bolted gates on beloved and significant landmarks are affectively jarring, and unlikely to be forgotten soon. Perhaps, however, these barricades can paradoxically become graphic reminders of civic responsibility – cementing community trust via sacrifice in the interest of public health during the ‘circuit-breaker’, phased re-openings and beyond.

I worry about the thinning out, even altogether evaporation of vital community services these important neighbourhood institutions provide, apart from spiritual labour. I fear an even further privatizing of socio-material support for the needy, peeling back another layer inwards.

Perceptibly, I consider the idea of the entrance to religious space – “The threshold that separates the two spaces also indicates the distance between two modes of being, the profane and the religious. The threshold is the limit, the boundary, the frontier that distinguishes and opposes two worlds – and at the same time the paradoxical place where those worlds communicate, where passage from the profane to the sacred world becomes possible” (Eliade 1959: 25).

(Source of Image on Left: Statnews)

I pass by this banner outside Toa Payoh Methodist Church in the early days before the circuit-breaker and again during. ‘This too shall pass’ - a timely reminder. A note-to-self. After checking the translation with colleagues, I learn for the first time that worship services are offered in Mandarin, Hokkien and Tamil here.

(Above: Screenshot from TPMC’s website)

I feel happy knowing the grounds of the Tree Shrine (Ci Ern Ge) are still being tended. The sanctum below the sacred Banyan tree houses Guan Yin as the resident main deity. The candles are lit. Other deities include Datuk Kong and Tua Pek Kong (beokeng.com).

“We must remember that we are sitting on a branch of Nature. If we cut the branch upon which we are sitting, we are bound to fall” (Satish Kumar 2020:42 in Resurgence & Ecologist 321).

I cannot find an official website for the Tree Spirit. Perhaps there can be no substitute for communion with a rooted, living, breathing ancestor.

In the morning sun the bougainvillea blooms cascade down the boundary wall of Church of the Risen Christ. A long-standing institution in Toa Payoh, the Roman Catholic Church has been offering community services to school children in the neighbourhood however I am unsure of the arrangements now.

(Above: Screenshot from Church of the Risen Christ’s official website) I am surprised to see virtual rosary recitations conducted in 5 languages: English, Mandarin, Tamil, Tagalog and Bahasa Indonesia.

A monk walks the temple grounds. A notice reads: ‘Lian Shan Shuang Lin Monastery (Siong Lim Temple, Twin Groves of the Lotus Mountain Temple). Announcement. From 25 March 2020, the Monastery and its adjacent Cheng Huang temples (City God Temple) will be temporarily closed until further notice. We thank you for your understanding and cooperation.’

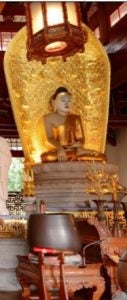

I glimpse the 7-storey Dragon Light pagoda from the walls to Singapore’s oldest Buddhist monastery. A statue of the Healing Buddha is enshrined in the Mahavira Hall (TP Heritage Trail 2014: 49). From the monastery’s website, I learn that the Bhaṣajyaguru Tathāgata (Medicine Buddha) holds ‘the power to heal and the ability to avert evil and prolong life’. I wonder if any special prayers, ceremonies and dedications are directed to Him during this time… (Left: Screenshot of Bhaṣajyaguru Tathāgata from the monastery’s website)

I glimpse the 7-storey Dragon Light pagoda from the walls to Singapore’s oldest Buddhist monastery. A statue of the Healing Buddha is enshrined in the Mahavira Hall (TP Heritage Trail 2014: 49). From the monastery’s website, I learn that the Bhaṣajyaguru Tathāgata (Medicine Buddha) holds ‘the power to heal and the ability to avert evil and prolong life’. I wonder if any special prayers, ceremonies and dedications are directed to Him during this time… (Left: Screenshot of Bhaṣajyaguru Tathāgata from the monastery’s website)

An unexpected, unmapped and unsigned private shrine… Gold characters emblazon the red banner with ‘Guanyin Fozu’ (Guanyin Buddha), an intimate addressal of the folk Chinese rendition of Guanyin as a ‘Fo’ (Buddha) gated within the altar. I have not encountered a male version of Guanyin before. On the left of this shrine stands a Maitreya Buddha and on the right, a Guan Di/ Guan Yu (Chinese God of War). A smaller open Earth Deity shrine stands sentinel nearby to the larger one, locked.

Pre-pandemic, I thought of this sculpture as the Protectress of the Polyclinic which She faces, now with the awnings up, temperature screening stations and marked queue lines branching across the courtyard and snaking up to the main road. Kaliamma as a protectress against illness, guarding against disease, must be all the busier. The presence of the Toa Payoh Polyclinic next door to Sri Vairavimada Kaliamman Temple is a sobering reminder of how we collectively are at the mercy of the times, oftentimes requiring more than essential biomedical assistance and all-important health institutions in place.

A notice informs devotees that ‘Only private worship, for a maximum of 5 members from the same household, will be allowed at any one time’. Information about SafeEntry is provided. ‘Prasadam will be packed for devotees to take away, if they have ordered one’.

(Above: Screenshots from the official temple website and Youtube channel)

I admire the beautiful floral latticework on the façade of Masjid Muhajirin. The locked gates create more geometric interlacing. While possessing a capacity for 2,800 congregants, the mosque’s official Facebook page visually presents social distancing procedures currently in place. An online booking form for Friday prayers is available. The mosque stands as a significant landmark built from collective community action – ‘The MBF [Mosque Building Fund] began collecting donations through the CPF [Central Provident Fund] in May 1975. Less than two years later, in April 1977, Toa Payoh residents witnessed the inauguration of their new mosque, Masjid Mujahirin’ (Jamil 2019). The mosque shares its premises with the Singapore Islamic Hub, Islamic Religious Council of Singapore (MUIS) and Madrasah Irsyad Zuhri Al-Islamiah. The mosque’s origins are in the Muslim Benevolent Society (Roots.sg), providing key community services.

Trawling through some websites, I learn about the main deity of Seu Teck Seng Tong Temple. Here, I paste an image of Grandmaster Song Da Feng in the middle photograph from the temple website, onto a blank notice board. One of the ‘Five-Word Golden Rules’ created by Him in order to make accessible the philosophical teachings of Buddhism includes a rule on ‘Illness’. Considering the susceptibility of the mortal human body to infection, the skills and services of physicians is invaluable, now so more than ever. I am awed and humbled by the medical charity work conducted by this temple.

Half-shuttered shrines, entries, exits bandaged with cordon-tape…A sign reads, ‘COVID-19 CB, NO ENTRY BY LAW’. The Wu He Miao (Five United Temples) was created to house five different temples founded during Toa Payoh’s kampung days. Deities of different dialect groups (Hokkien, Cantonese, Hainanese and Teochew) reside here (NHB 2014: 46). The grounds with its garden and outdoor seating areas, looks like it is an inclusive, common space under ordinary circumstances. Stackable, plastic chairs face downwards, tilted forward, still, absent presence. Everything seems emptied till I come to the front. Inside the red gates, two caretakers light candles and chat easily, caring for the deities unforsaken.

I am surprised to first chance upon this Taoist temple online via a blogpost. I then seek it out, in-between some HDB flats in Lorong 6. The main deity of the Poh Chung Tian Chor Sian Tong Temple is San Zhong Wang (transl. Three Patriotic King), ‘referring to the three patriotic officials Wen Tian Xiang, Lu Xiu Fu and Zhang Shi Jie, who lived during Southern Song Dynasty. They fearlessly fought the invading Yuan (Mongolian) army to protect their homeland, but unfortunately perished during that war. The people of Tong'an erected a temple in Hong Tang Zheng, Tong'an to honour their contributions, known as San Zhong Gong’. Other deities of the temple include Lord Qiu (Qiu Fu Wang Ye), Pu An Fo Zu (Qing Shui Zu Shi), Hong Fu Yuan Shuai, Guan Di (God of War), Five battalion Commanders (Wu Ying Shen Jiang), Da Bo Gong (Tua Pek Kong), Dark Tiger God (Hei Hu Jiang Jun) and Sen Luo Dian Da Er Ye Bo (Tua Li Ya Pek). This explains the pair of stone horse sculptures and the tiger relief. Although it is the 14th of July when I walk past, a notice on the main gate reads ‘In view of Covid-19 aligned with the government additional restriction and the safety of the public. Please be informed that we will close from 7th April to 3rd May 2020 as advised by the Government. The committee had decided to suspend all ritual & consultancy service until further notice…’ The phrase ‘until further notice’ encapsulates the suspension of time that hangs heavy in the air.

Tua Pek Kong, an Earth Deity, is being worshiped by the young and old, both masked and in quiet solitude. It is 8am on a weekday and the younger man (with a backpack) seems to be on his way to his workplace. The notice board next to the altar states ‘Please remove all food after offering. (For good health and good wealth) Thank you for your cooperation’. Due to the comparatively smaller scale of such spaces, no cordon tape or visual reminders for social distancing seem required. Protocol for prayer and piety seems to remain unchanged. I witness powerfully serene, purposeful, silent (intergenerational) rhythms and rituals of worship in a now much quieter neighbourhood wet market.

I must return to this altar perched on a shrub to figure out if a Ganesha or a Guan Yin stands draped in jasmine. The open parameters mean I can take a closer look on another morning. A quiet spot across the News Centre. A radical invitation for blossoming contemplation – from ego to eco.

“Historically pandemics have forced humans to break with the past and imagine their world anew. This one is no different. It is a portal, a gateway between one world and the next” (Arundathi Roy). The thresholds along so many facets of contemporary urban life are in some instances solidifying and in others evaporating unevenly. The origin of the word itself is ‘related to thresh (in a Germanic sense ‘tread’)’. Where do we go from here?

Acknowledgements: Thank you Dr Show Ying Ruo for helping me with translations and for opening my eyes to the many deities I was meeting for the first time.

Chand Somaiah is a Research Fellow with the Asian Migration cluster at the Asia Research Institute. Some of her research is available here.

Disclaimer: The views and opinions expressed in this article are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the position of the blog editorial team or the Asia Research Institute.

South Asia | Southeast Asia | East Asia | Other Places | Hinduism | Buddhism | Islam | Christianity | Other Religions