Inverted Sociality: Muslim Indonesia Celebrating Idul Fitri without Mudik

contributed by Finsensius Yuli Purnama, 7 August 2020

Fig. 1. Example of a picture expressing Idul Fitri greetings from the author's personal social media and messaging apps, May 2020

Mudik Culture as Part of Idul Fitri Celebration

Idul Fitri 1 Shawwal 1441 Hijri has just passed. In contrast to previous years, this year left a very deep impression for Muslims in Indonesia. The Covid-19 pandemic has led to new ways of celebrating holidays. Muslim Indonesia’s tradition of going home or “kampong halaman” (called mudik) and hospitality (called unjung-unjung) that is usually carried out had to be postponed. The Id prayers (solat Id), and takbiran and the series of the usual parade had to be abolished. Social distancing policies which have subsequently been revised to include elements of physical distancing, independent quarantine implemented with working, studying, and worshiping at home in Indonesia, as well as the PSBB or Large-Scale Social Restrictions policies have changed the new order of life and are regarded by President Jokowi on May 15th, 2020 as new normals, or new reasonableness.

One of the biggest changes in Indonesia is the increasingly limited physical closeness. Thus, the pandemic has raised the problem of proxemic distance. The theory of proxemic distance, developed by anthropologist Edward T. Hall (1966), explains the connection between how deep a relationship is by the measure of physical distance between two people communicating and their level of closeness. Hall made a measure that became a parameter of the closeness of two people who are communicating. He divided it into several categories, namely: intimate zones, personal zones, and social zones. However, in the middle of the pandemic, a personal closeness in the intimate zone or personal zone could not be achieved by Indonesian Muslim migrant workers due to Covid-19.

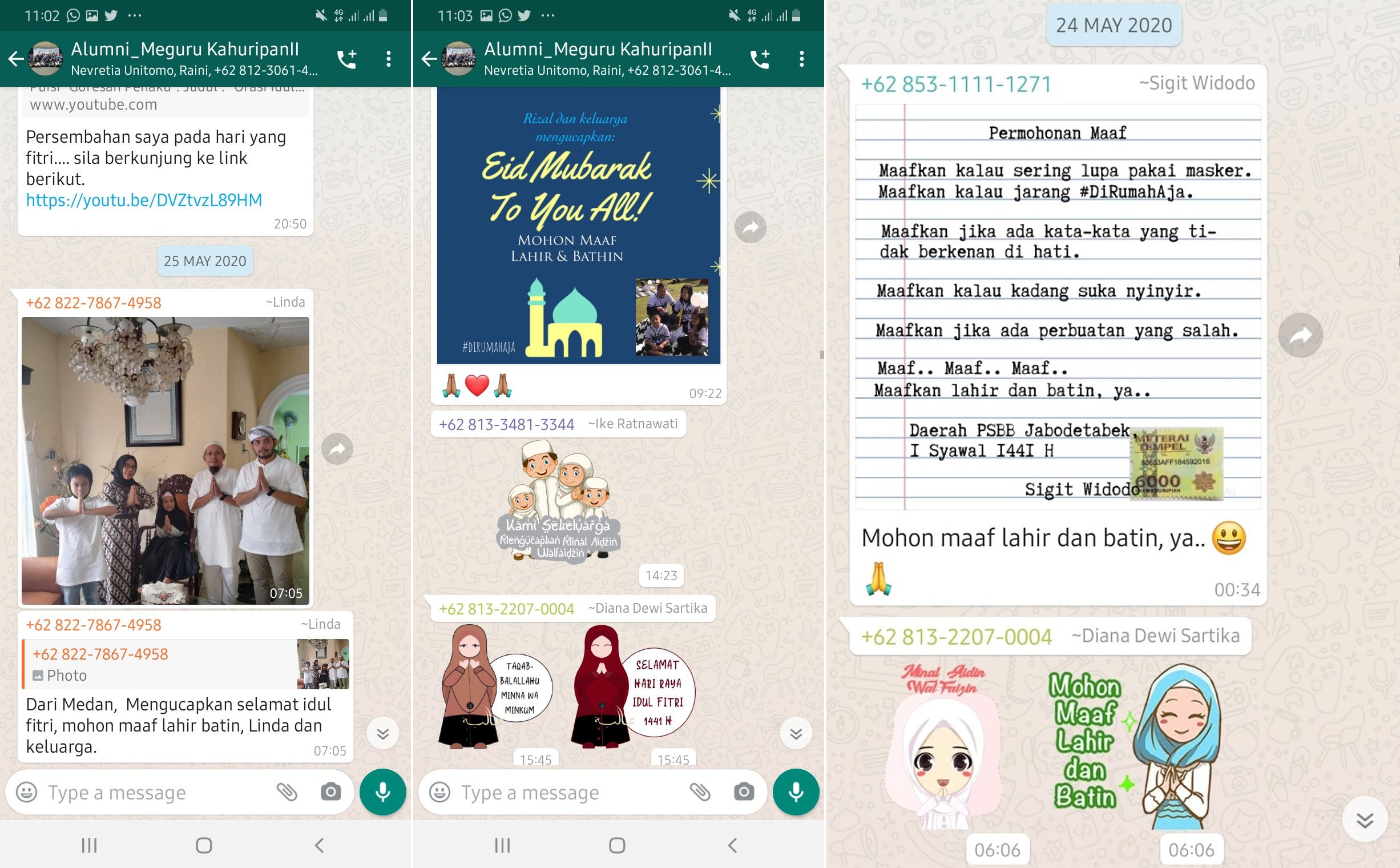

Various attempts have been made to overcome distance problems. One of them is by using video call applications, social media, and various applications to send messages and communicate with relatives or friends. This can be witnessed through the recent social media postings of screenshots of many online events with families and office mates in institutions such as universities, private companies, and state-owned enterprises (SOEs). People celebrated Idul Fitri by making some creative videos to express their greetings and the solitude of this ‘Selamat Hari Raya’ to families and friends. Many sent stickers digitally to one another to celebrate or ask for forgiveness via group-sharing applications such as WhatsApp and LINE. Evidently, technology helps people to meet virtually and involves limited visual code without any physical contact at all. This new adapted way of continuing relationships is what Budi Hardiman, an Indonesian philosopher, called inverted sociality.

Fig. 2-6 (above). Idul Fitri greetings and stickers from the author's personal social media and messaging apps, May 2020

The Adoption of Inverted Sociality

Physical distancing and limited touching are an important call in breaking the chain of Covid-19 spreading. The atmosphere is reflected by a Slovenian philosopher, Savoj Žižek, in the early part of his book through his popular quote of Noli Me Tangere, or "Don't touch me!" In his book ‘Pan(dem)ic!: Covid-19 Shakes the World,’ Žižek conveys the great ideals of the formation of global solidarity. Launched on March 25th, 2020, Žižek interpreted Noli Me Tangere as an invitation to human beings to build human values of love, and sharing of hope, no longer built on the notion of "contact", but on "vision".

The same awareness that has pushed the usage of the term ‘social distancing’ to ‘physical distancing’ was carried out by both WHO and the Indonesian government at the end of March as a form of affirmation that physical distance does not always mean psychological distance. People can interact with each other socially while maintaining the mandatory physical distance by communicating through social media or other messaging applications.

This is the era in which a new form of sociality is gradually developing. A relationship is no longer measured by proxemic distance. Closeness is no longer seen from how close physically people are communicating, but deeper than that, as closeness is judged by the intensity or the intent of one's actions. This is what is called an inverted sociality. The term inverted sociality is adopted from Edmund Husserl’s concept of sociality (Sozialität). Husserl understood sociality as “the intersubjective joining together of a subject” (Szanto and Moran 2016:108). In normal sociality, relationships and intimacy rely on physical encounters or tactility. People can go to a crowded place such as a music concert, and it gives a high sensation of closeness.

However, inverted sociality arises from an awareness where absence of proximity, or distance from others, is part of compassion and caring. The migrant workers (perantau) who decided not to go home to meet their families and neighbors in kampong or mudik have shown their concern in a very deep way. They did not mudik since they were aware of maintaining good norms of personal health and preventing the transmission of the Coronavirus. They pressured their ego not to meet physically for something bigger, that is, the health of others.

Thus, social distance is no longer a form of egoism, but a form of altruism. It is an awareness in the form of keeping a physical distance for the health of others and ultimately ourselves as part of the community. In the uncertainty of when this pandemic will end, it is important to develop a new way of relating that is most likely to be done while people still have to comply with physical distancing measures. This Idul Fitri celebration has reflected a picture of how people, in this case Muslims in Indonesia, have interacted in new ways and maintained social distancing to break the chain of Covid-19 transmission. Keeping a distance has a deep meaning during this pandemic. It is an expression of love, and of love in a new form.

References

Hall, Edward T. 1966. The Hidden Dimension. Anchor Books.

Szanto, Thomas and Moran, Dermot. 2016. Phenomenology of Sociality: Discovering the ‘We’. New York: Routledge.

Žižek, Slavoj. 2020. Pan(dem)ic!: Covid-19 Shakes the World. New York: OR books LLC.

Disclaimer: The views and opinions expressed in this article are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the position of the blog editorial team or the Asia Research Institute.

South Asia | Southeast Asia | East Asia | Other Places | Hinduism | Buddhism | Islam | Christianity | Other Religions

Finsensius Yuli Purnama currently is an ARI - Asian Graduate Student Fellow 2020. Currently he is a doctorate student at Gadjah Mada University, and also a lecturer at Widya Mandala Catholic University, Surabaya. Moreover, he has been a volunteer in MAFINDO (Indonesian Facebook Flagger) and as a social media researcher at Drone Emprit Academic. IG: Fins Purnama, Twitter: @Finspurnama, Fb: Fins Purnama, Linkedin: Finsensius Yuli Purnama