The Pandemic and Shifting Practices of Islamic Charity

contributed by Amelia Fauzia, 28 August 2020

The Shifting Practices of Islamic Charity during a Pandemic

The Covid-19 pandemic has led to a shift in the practices of Muslim communities and Islamic charitable organizations in Indonesia. The pandemic not only has forced them to improve their fundraising methods but has also encouraged a jurisprudential review in charitable management and distribution to follow a more effective, safe and beneficial strategy in mitigating the spread of Covid-19. The shift moves towards more rational and substantial practices which put greater emphasis on the broader interest of society and humanity.

Indonesian Muslim charitable organizations have responded by intensifying their use of digital technology especially for fundraising (see Covid-19 and the blessings of online zakat) and distribution programs. Some organizations have quickly realized that they need to provide assistance for anyone affected by the pandemic regardless of religion and not merely their own Islamic congregations.

Fig.1. Lazismu, an Islamic Charitable Organization, spraying disinfectant at the Evangelical Indonesia Church in Ngawi, East Java, March 2020. Picture: courtesy of Lazismu

Revisiting practices, encouraging innovation

The pandemic has provided charitable organizations an opportunity to review their practices and programs, including their Islamic jurisprudential foundations. The need for urgent action to prevent the loss of human lives as well as to prevent further deterioration of the state of the economy has become a significant reason for adopting practices that are regarded as controversial and are unpopular amongst some congregants. For example, using zakat and sedekah (alms) money for programs that involve non-Muslim beneficiaries, while common for international Islamic charities, has proven to be a challenge in the Indonesian context. If it were not for the pandemic, organizing the spraying of disinfectants within public spaces and houses of worship, including churches and Buddhist temples, would have received criticism.

One organization that is prominent in adopting these broader-based charity activities is Lazismu, a zakat and charitable body under Muhammadiyah, the second largest Islamic organization in Indonesia. Within the last few years, Lazismu’s religious board has outlined that the distribution of its zakat and sedekah is non-discriminatory and inclusive to non Muslims, as there is no regulation in the Qur’an that limits it to Muslims. During the pandemic, Lazismu’s non-discriminatory policy is even more visible and public. Executive Director of Lazismu, Mr Edy Suryanto, mentioned that Lazismu’s Covid-19 prevention programs included spraying disinfectants in mosques, churches and temples as places that have the potential of spreading the coronavirus. He explained that the activities have been executed in a number of provinces, especially in Central Java, East Java and Eastern region of Indonesia. Lazismu also provided a large number of hazmat suits for hospitals that treat anyone regardless of religious affiliation.

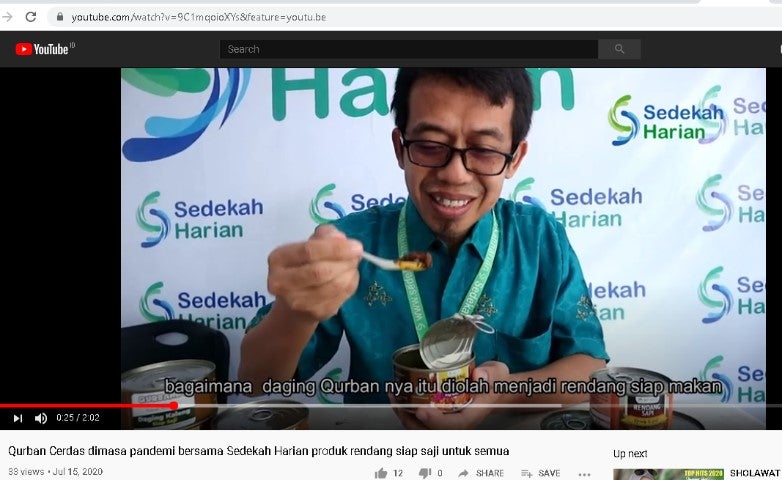

Fig. 2. Social Media Flyer with statistics of Lazismu’s Covid 19 Aid up until May 2020

Another example of a new innovation is the broadening of the zakat fitrah distribution limit. Usually, the distribution of zakat fitrah must be done before the Eid prayer in the morning. However, given that the majority of fitrah payments are done the night before Eid al-Fitr, it is very unlikely that the money could be distributed effectively to the poor before the 7am prayer. How would they manage to distribute millions or even billions of rupiah within such a short period to the poor while also adhering to social distancing measures? As Lazismu receives 70 percent of fitrah payment at night of Eid, it improvised by adopting a legal innovation, by which zakat fitrah could be distributed within a six-month period.

The last example is a review and innovation in the qurban practice known as udhiyya (Arabic for sacrifice by slaughtering animals). Criticism against this practice has long been expressed as it has often been considered as a waste of charity due to its lack of long-term benefit for the poor. Some large organizations such as Dompet Dhuafa, Rumah Zakat and Lazismu have been trying to find an alternative way by creating programs that can empower cattle and goat farmers, as well as preserving the meat of the slaughtered animals in canned food packaging so that it can last for a longer period. During the pandemic, more organizations have stepped in to start directing the conventional qurban into slaughterhouses and packaging the meat into ready-to-eat meals.

Fig. 3. Video promotion of canning the qurban meat, screenshot from https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=9C1mqoioXYs&feature=youtu.be

A charity organization called Sedekah Harian started a program called Smart Qurban (Qurban Cerdas). It promotes a ‘smart’ way to do qurban during a pandemic, which includes avoiding crowds, hygienically packaging the meat, allowing consumption up to two years, providing a ready-to-eat dish with Indonesian rendang taste, and organizing it to serve double benefits - as part of food security program. During an interview, its director, Mr Abdul Azis, explained that his organizations have had a conventional qurban program for years, but due to the pandemic, they provide a new option of canned food.

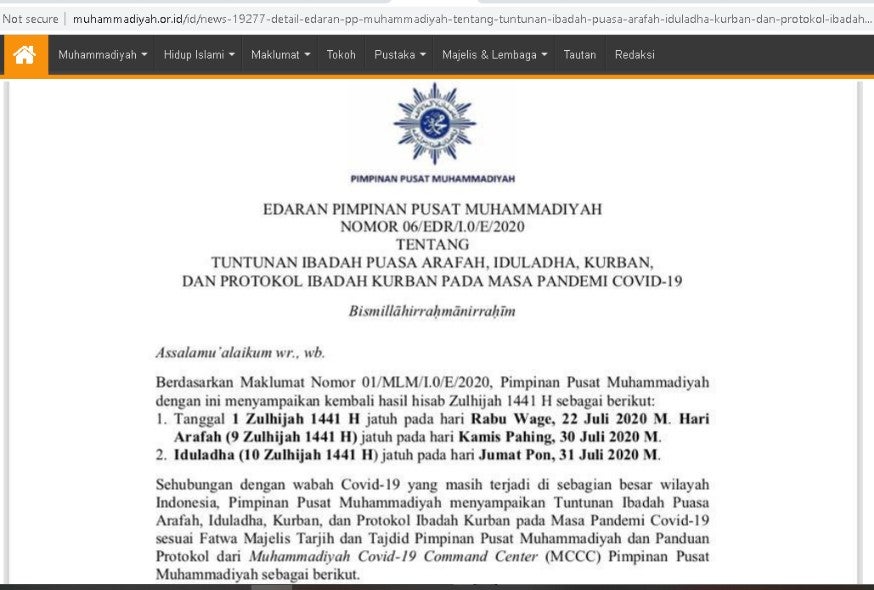

Fig. 4. Advertisement of canned qurban meat. Retrieved from Lazismu’s website on August 24, 2020. http://www.lazismujatim.org/?p=2940

The Public Interest

The above examples show how the Covid-19 pandemic has provided opportunities to promote ideas in transforming religious charities. Lazismu and Muhammadiyah organizations were brave in reviewing and transforming the practice of qurban. Muhammadiyah issued a circular (no 06/EDR/I.0/E/2020, dated 24 June 2020) on celebrating Idul Adha and conducting qurban, based on the study of Muhammadiyah’s Fatwa and Religious Reformation Council (Majlis Tarjih & Tajdid). Bringing awareness to more healthy and effective ways to conduct qurban, it suggests that “giving something which is more beneficial for the public good is a priority” (p.1, C.4). Although it does not prohibit conventional qurban practices, Lazismu has encouraged a shift towards canned meat -- “RendangMu” -- and increased education to prioritize giving cash donations for Covid-19 programs rather than for qurban. Its circular further says “the law of Qurban is sunnah muakadah [voluntary act of worship] for any Muslim who has the ability to do it... The Covid-19 pandemic has caused social and economic problems and increased the number of poor people. Therefore, we suggest that Muslims who have the ability to perform should prioritize giving donations in money rather than giving sacrifice by slaughtering animals” (point C.1 and C.2).

Fig. 5. Muhammadiyah’s circular on Idul Adha posted on the official website (http://www.muhammadiyah.or.id/id/news-19277-detail-edaran-pp-muhammadiyah-tentang-tuntunan-ibadah-puasa-arafah-iduladha-kurban-dan-protokol-ibadah-kurban-pada-masa-pandemi-covid19.html)

Therefore, we see how Muhammadiyah and Lazismu’s message took advantage of the pandemic’s momentum by not only endorsing reform towards effective giving, but also educating their constituents on religious jurisprudence. The Lazismu move is a warm welcome, but still there is disagreement and controversy. Commenting on that, the director of Lazismu smiled and said that “we are used to dealing with controversy”.

Disclaimer: The views and opinions expressed in this article are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the position of the blog editorial team or the Asia Research Institute.

South Asia | Southeast Asia | East Asia | Other Places | Hinduism | Buddhism | Islam | Christianity | Other Religions

Amelia Fauzia is Professor and Head of Magister Program in Islamic History and Civilization, Faculty of Arts and Humanities, Syarif Hidayatullah State Islamic University, Jakarta. She is also a Senior Visiting Fellow at School of Humanities and Social Sciences, University of New South Wales (UNSW) at Canberra. She could be contacted at ameliafauzia@uinjkt.ac.id.