Do the Gods Have COVID-19 Too?: Protecting Idols, Cherishing Deities

contributed by Indira Arumugam, 3 September 2020

Fig 1: Diagnosing Deities for Virus, UP. Credit: Unknown, Source: WhatsApp

“Do the gods also have the Coronavirus? Doctors diagnose in person”, reads the headline of a Tamil newspaper article about the Jagannath temple in Uttar Pradesh (UP), India. Under the orders of the monk-cum-chief-minister of the state, doctors are seen holding a stethoscope to listen to the internal sounds of a statue, and to search for the heartbeat of stone.

This act of medically examining essentially inanimate and insensate material and simultaneously an omnipotent and presumably invulnerable deity provokes questions about the interplay between the material and the metaphoric in the constitution of the sacred.

Focusing on how the stone, plaster and metal idols of deities in Hindu temples are handled with respect to the safety precautions made imperative by a viral pandemic, I explore the dynamics of matter, energy, intentions and actions that go into sculpting substance into sacrality. In doing so, I show how anthropomorphic poetics underlie the worship of deities in/through/ as stone and metal idols and confounds the boundaries between objects, humans and the divine.

Protecting the Deities’ Statues

Icons of deities wearing surgical masks started appearing in the news, even before the Covid-19 pandemic, when New Delhi was affected by particularly dangerous levels of air pollution at the end of 2019.

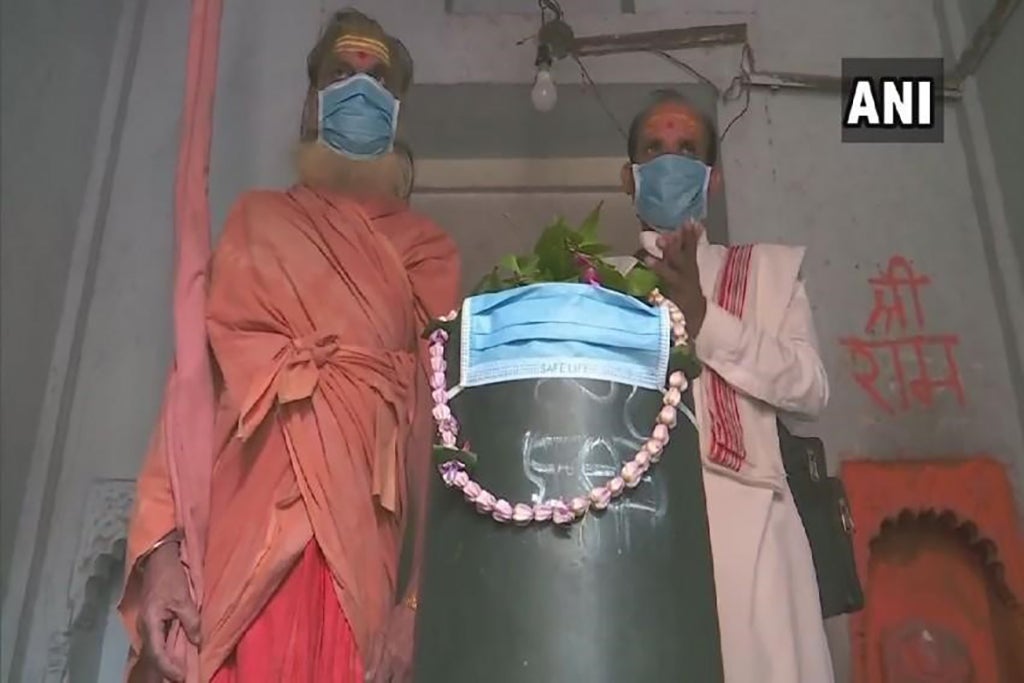

Fig 2: Facemask on Shiv-ling to Protect against Toxic Air, Varanasi, UP, India, Nov, 2019. Credit: ANI

Fig 3 : Deities Wearing Masks Against Air Pollution, Varanasi, UP, Nov 2019. Credit: IANS

When asked why they had put masks on the icons, the priest at the above temple explained,

“How can we allow the pollution to affect the gods.... we are wearing masks to protect ourselves... we should also think about the gods.

Our deities are believed to be in human forms. We provide them with all the earthly comforts. In summer, we rub sandalwood ointment on idols for coolness. They are given blankets and sweaters in winter. When we worship them in human form then they must be getting affected by pollution as well”

As such, in February and March 2020 when COVID-19 became pervasive in India, masks were put on the gods to protect them from this dangerous miasma as well.

Fig 4: Mask Wearing Deities, Precautions against COVID-19, Sitamarhi, Bihar, Mar 2020. Credit: Unknown, Source: TNN

Fig 5i: Shivling Wearing Mask Against COVID-19, Varanasi, UP, Mar 2020. Credit: ANI

Fig 5ii: Shivling Wearing Mask Against COVID-19, Varanasi, UP, Mar 2020. Credit: New Indian Express

‘Idol Worship’

There are two main ways in which idols have been thought of in Hinduism. Firstly, the icon is a metaphor. The idol is not the ultimate end; it is a manifestation of an essence. It refers to another and ultimate reality. Leveraging the purchase and resonance of the deities in Hindu society, mask-wearing idols are symbolic resources used to educate the public about the pandemic and reiterate the importance of public health initiatives. A priest explained this as a symbolic gesture: “Coronavirus has spread across the country. We have put a mask on Lord Vishwanath to raise awareness about coronavirus”. Mask-wearing idols are physical representations highlighting the existential threat of the disease, as well as the practical rituals adopted by people to grapple with this seemingly ineffable peril.

Secondly, and also relatedly, the icon is a vehicle. The idol is not merely just an object of worship, but a means through which the numinous inhere to a specific time and place. It is a vessel for divine energies although the divine itself is not contained by it.

While Hindus believe that anything and everything may potentially be worthy of worship, objects have to be made sacred through intentions, incantations, rituals, worship and care. As soon as it is invested with and as long as it holds these divine energies, the vehicle too, is sacralised.

The Image is Material

At the same time, the icon is material too. In reference to COVID-19, the icons themselves were cleaned, sprayed and disinfected.

Fig 6: Disinfecting Icons Before Opening Up for Worship, Bengaluru, Karnataka, June 2020. Credit: PTI

Fig 7: Sanitizing Shivlings, Prayagraj, Uttar Pradesh, June, 2020. Credit: AP

Fig 7, 8: Priest Sanitizing Icons, Prayagraj, Uttar Pradesh, June 2020. Credit: AP

Along with masking deities, priests in Varanasi are also “urging people not to touch the idols to prevent the spread of the virus. If people touch the idol, the virus will spread and more people will get infected”. Thus the icon, like any other material, is also understood as a potential vector for disease.

The Image is Alive

In theological frameworks, the deity cannot be equated with its image. And yet this image is much more than simply an object. The idol is not just treated as though it is sacred but as if it were the deity itself. It is not treated merely as a metaphor or a medium but as though it were alive. As such, sacred idols trouble the boundary between organic and inorganic, human and divine, potency and intimacy, and material and metaphor.

Presuming them to be living deities is why the icons are covered with woollen clothing to keep them warm in winter, slathered with sandalwood paste and provided with air-conditioning to keep them cool in summer and face masks to protect them from air pollution. This is also why they are made to wear surgical masks and subjected to medical examinations to protect them against COVID-19.

Idols are the divine in not just material but also ‘human’ form. The gods/icons experience the pleasures that embodiment makes possible. Simultaneously, they are also subject to its vulnerabilities including heat, cold and illness. The care that priests lavish on the icons underlines an intimacy amidst the wonder and terror the icons also inspire, and through which Hindus engage with their deities.

Describing how the idols of Hindu deities are sprayed and sanitized as materials but also simultaneously cared for and protected like humans, I demonstrate how they are deemed a source of infection but yet simultaneously perceived to be vulnerable to the virus. At the same time, they contain immense and almighty cosmic energies that cannot be delimited to, and by their confines. Though they may appear inorganic, idols frequently confound the divide between that which is alive and that which is too inanimate to exhibit liveliness.

While the COVID-19 situation has accerbated the phenomenon, it must be noted that even regular worship services in temples involve the deities/ icons being woken up, bathed, dressed, decorated, fed, sang to, entertained, married to each other, left alone to make love and put to sleep. It is this anthropomorphic poetics that presumes icons not just to be alive with the deities but also lively with experiences, pleasures and desires. Indeed, they are assumed to be open even to the vulnerabilities that plague humans.

This expansive imaginary – an assemblage of materiality, humanity and sacrality – is what prompts people to extend an ethics of care to idols through worship. While made from the most inert of substances, as they unite with humans, stone and metal idols do not just become sacred. In the process, they have also become storied, sensate and perhaps even a little sentient.

Indira Arumugam is an Assistant Professor at the Department of Sociology, National University of Singapore. An anthropologist, working in Tamil Nadu, India and among the Tamil diaspora in Singapore, her research interests include ritual theories, political theologies and material religion. She has published extensively on the gift, animal sacrifice, kinship and pleasure.

Disclaimer: The views and opinions expressed in this article are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the position of the blog editorial team or the Asia Research Institute.

South Asia | Southeast Asia | East Asia | Other Places | Hinduism | Buddhism | Islam | Christianity | Other Religions