Prayers, Protocols and Pandemics, Part 1: Do My Ancestors Need Masks? The Impact of Coronavirus on the Seventh Lunar Month Festivities in Singapore

contributed by Esmond Soh, 10 Septmeber 2020

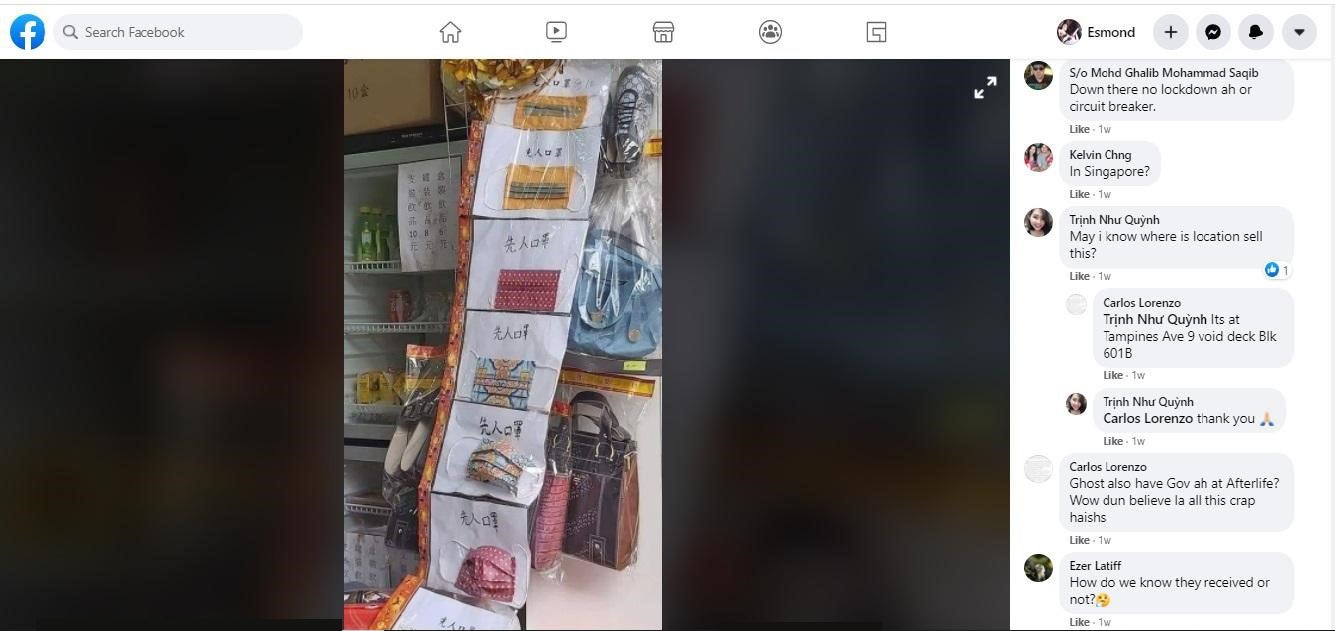

Figure 1. Source: Victor Yue, “[7th Month Festival] The ancestors still received their favourite food and goody bags!,” 29 August 2020, in “7th Month Festival Singapore,” Photograph courtesy of Mr. Victor Yue

Joss paper, as well as paper effigies of goods associated with this world (Figure 1), are indispensable offerings at any observation of the seventh lunar month in Sinophone societies, and Singapore is no exception to the rule. Just before the seventh lunar month, a friend texted me a photograph of a shop that specialised in the sale of prayer paraphernalia (Figure 2A). Such shops typically escape the radar, but this particular shop stood out for its sale of papier-mâché surgical masks. Given that Singapore had implemented a law requiring individuals to wear a face mask whenever they are outdoors since April 2020, this photograph caused quite a stir. Was there a pandemic of similar proportions in the netherworld? Would the deceased know how to use them? How many should we purchase for the dearly-departed? Was there a supernatural Green Lane that connected the netherworld with Singapore? In this post, I explore how conceptions of the spirit-scape of Chinese popular religion have shaped, and have in turn been shaped by the measures implemented in the second phase of Singapore’s re-opening since the April-June Circuit Breaker (CB).

Figure 2. Source: Chris Goh, “Ghost month coming soon, anyone need mask can pm me,” COMPLAINT SINGAPORE, Facebook photo, August 16, 2020

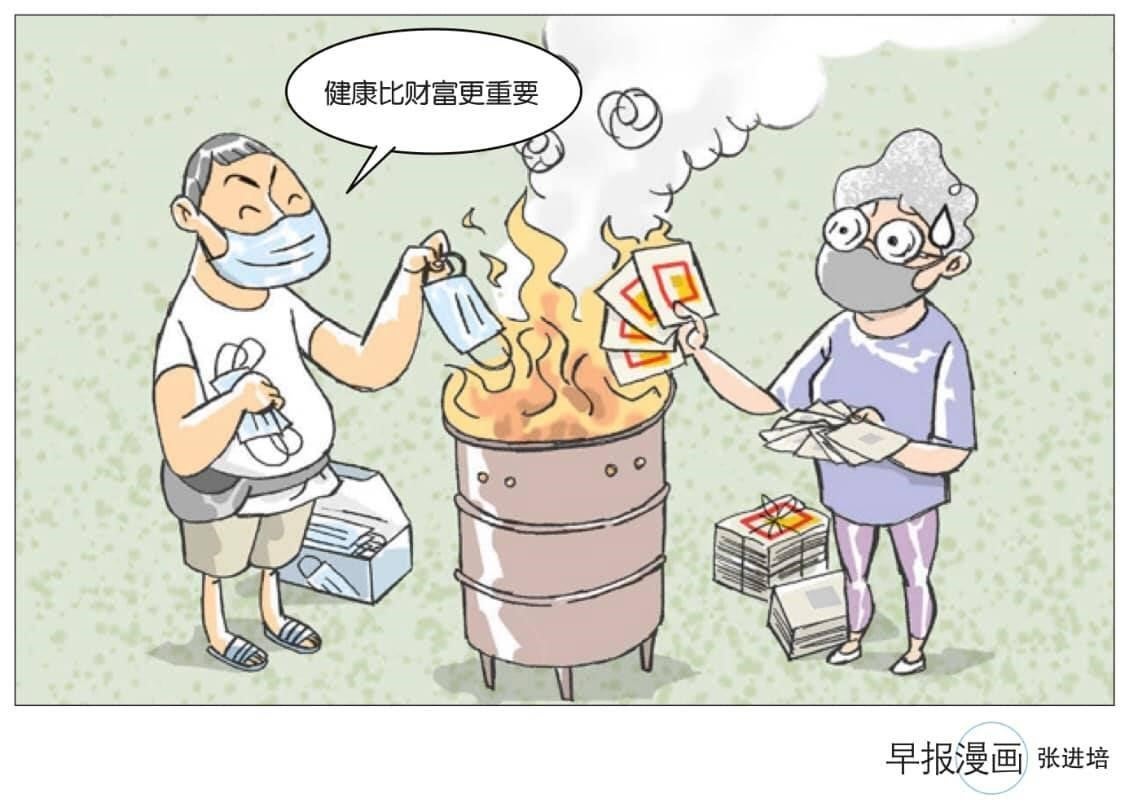

The provenance of this photograph was eventually traced to a store in Hong Kong, although a discussant suggested that one such shop in Tampines specialised in the sale of the said-accessory (see figure 2B, “Carlos Lorenzo”). More recently, the Chinese press published a similar cartoon, where a devotee chose to incinerate face masks rather than joss papers because “staying healthy is more important than being wealthy” (Figure 3).

Images like these reflect how divisions between the otherworld and this-world are fluid and porous in some Chinese religious belief systems. Students of Chinese religion continue to debate Wolf’s arbitrary division of the Chinese spirit-scape into gods (officials), ghosts (strangers) and ancestors (family) (and more recently, gangsters). In practice, the divisions between the three feed into one another, where ghosts can potentially ascend to the position of gods, and whereby strangers to one family serve as the ancestors of another. Weller, in his study of the seventh month celebrations in Taiwan made this point clear: while ghosts are supposedly ‘outsiders’ based on Wolf’s schema, they are also hosted by the community over the month. Depressingly, the reverse was also true, where people could also be juxtaposed into the position of ghosts. Rural Taiwanese celebrants in Weller’s study, for example, were consistently exposed to the plight of senior citizens in their midst after they were abandoned by their children (who absconded to the city in search of better opportunities).

Figure 3. Source: Jinpei Zhang, Lianhe Zaobao, 26 August 2020, Wednesday. Speech bubble reads “Staying healthy is more important than being wealthy.” Special thanks to Lynn Wong Yuqing for bringing this cartoon to my attention

Figure 4. Source: Hancong He, Lianhe Zaobao, 29 August 2020, Saturday. The grandmother spirit complains that “my (her) children and grandchildren didn’t burn any (masks)” for her to use, whereas the guard on the left insists that “you must have a mask in both the netherworld and the human world.” Special thanks to Lynn Wong Yuqing for bringing this cartoon to my attention

While I caution against overreading into the intentions of its buyers and sellers, a papier-mâché surgical mask, when presented to deceased ancestors, can serve as an expression of one’s love, concern and filial devotion to the recipient given the overlap between the worlds. Whether the otherworld is experiencing a similar pandemic, I do not know, but spirit-scapes, particularly those associated with the “nameless but active religion” practiced by many Chinese (including myself) are malleable and responsive to this-worldly conditions and needs.

Intriguingly, the surgical mask was meant to be burned for one’s ancestors (see a similar sentiment expressed in Figure 4), and did not feature as a run-of-the-mill offering for wandering spirits who need to be placated, rather than worshipped. Paper offerings which typically serve to restore “social distance” (pun intended) between the living and the appeased dead after they are incinerated are not created equal: more elaborate and costlier effigies (iPads, cars and surgical masks) serve to entrench the ties that bind this-worldly descendants with their otherworldly ancestors (Figures 5 and 6), whereas more generic offerings – addressed to none – serve as bribes to the nameless and unknown “good brothers” (an euphemism for ‘wandering ghosts’).

Figure 5. Source: The author, “Joss paper offerings in a shop, Woodlands, Singapore,” 30 August 2020

Figure 6. Source: The author, “Writing the deceased recipient’s particulars on joss paper offerings,” 30 August 2020. My father (in a light shirt with green sleeves) instructs the shopkeeper on the spelling of my great- and grandparents’ names on the yellow slips of ‘goody bags’ filled with joss papers and ingots

Figure 7. Source: MediaCock Singapore, “Remember to wear mask ... arbo SG$300,” Facebook photo, August 18, 2020. One of the ten kings of Hell is featured in the first panel of this meme. Also note the queue of spirits who are waiting to leave the netherworld in a manner similar to the clearing of immigration customs

Figure 8. Source: SemiSerious, “The ‘tourists’ are back!” Facebook photo, 19 August 2020. The overhanging title reads “Singapore.” Ox head and horse face are two jailors in the Chinese netherworld. Note the comment by “Say Beng Teoh” on the humour of the portrayed situation

While jokes and memes have been made to ‘visualise’ the impact of COVID-19 upon the netherworld’s operations during the seventh lunar month, sources like these not only serve as a means of entertainment. Rather, they also provide an insight into how Singaporeans think and situate themselves within the gamut of measures implemented to curb the spread of COVID-19 in the community. Conceptions of the Chinese netherworld as a sprawling bureaucracy with kings, courts and enforcers (Figures 7 and 8) – as discussed elsewhere and repeated through various incarnations, including dramas set in Singapore – had found ready parallels with the measures employed to check the contagion in Singapore.

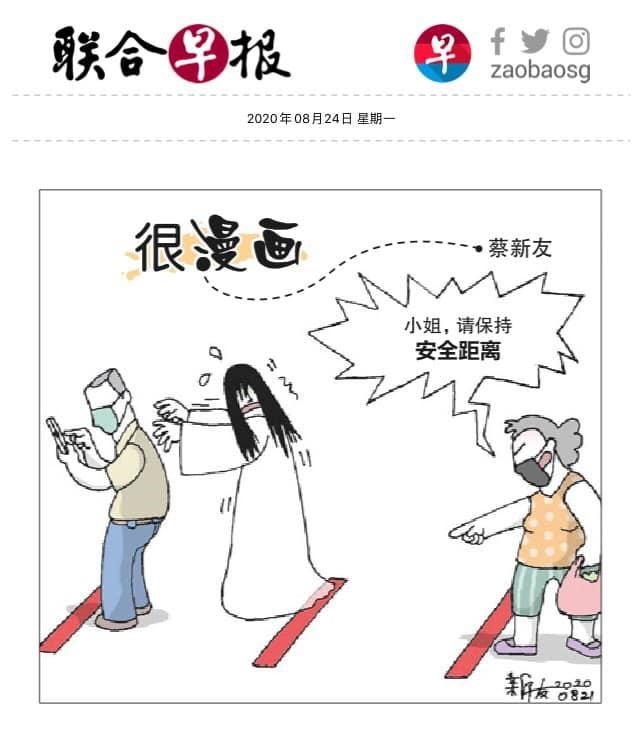

Figures of authority recognisable to many Singaporeans in a post-COVID-19 world, such as Safe Distancing Ambassadors (SDAs) and staff dedicated to checking one’s temperature, have their duties juxtaposed (and occasionally inverted) vis-à-vis otherworldly environments and its denizens (Figures 4, 7, 8 and 10). Kings of hell insist that their subjects wear masks before they can be released for their ‘holiday’ on earth, lest the latter be slapped with a punitive $300 fine (Figure 7), a feature reflective of a similar rule in Singapore. Humorous interpretations like these – while not literal and meant as tongue-in-cheek commentaries – have certainly struck a chord among Singaporeans, given the prevalence of regulation and enforcement that has penetrated into almost every aspect of life.

Figure 9. Source: Xinyou Cai, Lianhe Zaobao, 24 August 2020, Monday. Speech bubble reads: “Miss, please maintain safe distancing.” Special thanks to Lynn Wong Yuqing for bringing this cartoon to my attention

Figure 10. Source: Taili Li, Lianhe Zaobao, 20 August 2020, Thursday. Sign reads “Before entering (the premises), please take your temperature.” Note the parallels between the temperature taker in this cartoon with the position of ox face in Figure 4. Special thanks to Lynn Wong Yuqing for bringing this cartoon to my attention.

Regardless of their setting – either in this-worldly Singapore or the netherworld – memes and cartoons that revolve around this theme all agree on one point: there is a ‘ghost’ whose movement was restricted by one regulation or another, and there is an authorised personality in place to enforce these measures. Just as organisations and businesses can refuse entry for patrons who do not wear masks properly or provide details for contact-tracing, wandering spirits are not allowed to holiday in Singapore without having their temperatures checked and details scanned (Figure 8). Cartoons poke fun at how the “good brothers” are not spared from the disciplinary power associated with such precautionary measures (Figures 9 and 10), but the implicit absurdity of these cartoons, I believe, also provides a safety valve to refract – rather than reflect – incumbent fatigue and anxieties associated with the pandemic’s prolonged uncertainty and sway over daily life. Humour – and how even ghosts have to be subjected to the same banal processes many Singaporeans are familiar with – thus provides a round-about way to express sentiments of uncertainty and exhaustion.

This compressed discussion on how the nexus between spirit-scapes, the seventh month festivities and popular culture in Singapore have been affected by the post-CB measures since June 2020, to be sure, cannot do justice to a complicated and variegated phenomenon. However, as I have pointed out, spirit-scapes – and popular conceptions of the spirit-world – have started to assimilate certain aspects of living in Singapore during such trying times. In other cases, representations of the spirit-scape can serve as a means of expressing how tired Singaporeans are with the extended siege against COVID-19. These are interesting areas that should be probed to better unpack the outlook of Singaporeans during this time, but even that, I am afraid, will have to wait until phase three. Only time will tell.

Disclaimer: The views and opinions expressed in this article are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the position of the blog editorial team or the Asia Research Institute.

South Asia | Southeast Asia | East Asia | Other Places | Hinduism | Buddhism | Islam | Christianity | Other Religions

Soh Chuah Meng Esmond is a History graduate student enrolled in the Master of Arts program at the Nanyang Technological University, School of Humanities (SoH), Singapore. His research interests include the history of religion, diasporic Chinese religion and the history of the overseas Chinese in Southeast Asia.