Shaping and Reshaping Traditional Culture in Bangladesh: The Folklore of Corona Times

contributed by Saymon Zakaria, translated from Bengali by Carola E. Lorea, 1 October 2020

In the pathways of history, the people of Bangladesh have gone through natural disasters, political turmoil, and man-made catastrophes. In response, they have fought, resisted and survived using their resourcefulness. Traditional cultures in Bangladesh have always been used as a way to increase spiritual and mental strength, as well as nourish the resourcefulness needed to face problems in everyday life.

The movement to establish Bengali – the mother language – as the national language from 1948 to 1952 and the war for Independence in 1971 stay as potent testimonies of this fact. During those time periods, traditional folk songs were mobilised; folk singers composed new songs and performed them to feed peoples’ courage and inspire them to join the struggle. Almost every year, when swollen rivers break into floods on the chest of this land, traditional songs provide mental force and resilience to all people in difficulty. As an oral vehicle of the people’s messages, traditional folklore and folk songs have fuelled the fight of the common people by providing confidence in the midst of floods and natural disasters that are part of daily existence in Bangladesh. These songs contain the very instructions that teach people to survive. There will always be folk singers and folk composers who come forward with their new songs to keep on spreading this message of resilience.

The time of the Corona pandemic was no exception to this rule.

With the Corona pandemic came the directive to maintain social distancing norms. To implement that, the government called for a lockdown. A massive danger came to challenge the impoverished people living a hand-to-mouth existence, who were reluctant to follow the prescribed medical regulations. Lacking education, for common people in this country expressions like “lockdown” and “social distance” are far from intelligible. Equally unintelligible are the convoluted Bengali equivalents for the phrases – “swasthobidhi mene colun” [follow health regulations] and “samajik durotva rokkha korun” [maintain social distance]. In these circumstances, several folk poets and folk artists of Bangladesh took the initiative to spread a message of social awareness from their own homes, composing new songs and recording their performance for social media platforms like Facebook and YouTube. Instead of simply composing poems and reciting verses about disease prevention and safety, some have also started to sell face masks, hand sanitizers and gloves at the crossroads to secure a small source of income. This article aims to look at some of the transformations brought about by the folk artists of Bangladesh and their creativity.

The first case of coronavirus aka COVID-19 infection in Bangladesh dates back to March 2020. On April 5th, Sonkor Day, a young folk singer and performer of Folk Ramayana (Ramamangala) from the district of Kishoreganj, wrote to me. He had composed the lyrics and melody of a new song to spread social awareness about the virus and sent it to me via Messenger, together with the kind request to share the song through the Facebook page of the Bhabanagara Foundation. We asked why he wouldn’t just share the song through his own Facebook page. Sonkor Day then replied that his Facebook profile is not very popular, and wouldn’t be reached by many people. But if the song is shared via Bhabanagara then it will reach the entire country and make more people aware. The artist’s interest, as we can understand from this request, is really to maximise the reach of exposure to the greatest number of listeners in order to spread awareness about safety and prevention from spreading the coronavirus.

Before discussing Sonkor Day’s endeavour, a few more words about his background are needed. Sonkor Day resides in Kishoreganj, in Mymensingh division. He is a disciple of the well-known Ramamangala artist of that region, Gopal Modak. Together with his guru, they perform in temples and private functions all over the area, singing the stories inspired by Hinduism. At present, Sonkor Day has his own troupe of musicians to perform Ramamangala independently. During the corona pandemic, however, the folk singer Sonkor Day decided to play a different role. He started to compose lyrics and melodies of new songs in order to bring awareness to the poorly informed people of this country. These are some lines from his song:

Stay away from each other please, do not come close together

Do not allow the disease to spread by touching hands

If you have a cold or cough please go to see a doctor

Don’t sit idly at home spreading rumours.

Following [Prime Minister] Sheikh Hasina’s request help stopping Corona

Allah is there above, there is no reason to fear.

Do not allow the disease to spread by touching hands

No need to go to the tea stall and sit to chit-chat

Listen oh Bengali people, listen to Sheikh Hasina’s offering:

Nobody will be left starving in our golden Bangladesh.

Use Bengali soap to wash your hands properly

Don’t ever eat with your unwashed hands, my brother!

The readers are warmly invited to listen to the full recording of the song at this link.

In his words, the artist refers to not only the cultural habits of the Bangladeshi people, but also hints at the current gossip around coronavirus. Stating the initiatives of the government, he infuses courage in people’s hearts. It is important to note that Sonkor Day is a follower of Hinduism but in his song, in the couplet referring to the honourable prime minister Sheikh Hasina, he says: “Allah is there above, there is no reason to fear”. Referring to the ongoing rumours, he alludes to the fact that since the very start of the Corona pandemic certain groups of people in Bangladesh have been responsible for spreading misinformation. A few Islamic fundamentalists and their followers in Bangladesh have started circulating these rumours as soon as the pandemic started. Among others, one in particular, Mufti Kazi Ibrahim, in the beginning of March in a public sermon (mahfil) as well as during Friday prayers at the mosque, narrated the visionary dream of a Bangladeshi national residing in Italy, Mamun Maruf, who interviewed the virus. The virus revealed to him when and where it will arrive on Earth. These rumours were used to publicise the views of Islamic fundamentalists, who used their coronavirus narratives to display hatred towards other religious communities and other forms of Islam as deviant by referring to the Covid outbreak in Iran. Mufti Kazi Ibrahim mentioned that there will be no coronavirus here in Bangladesh (“ekhane Corona asbe na”) because people laudably follow the religious norms of Islam. In addition, he also mentioned that those who do not follow Islam will not be spared by the virus. His sermon was circulated widely through social media and swiftly became ‘viral’.

Fig. 1. Screenshot of Mufti Kazi Ibrahim’s sermon posted on youtube

Fig. 2. Another sermon by Mufti Kazi Ibrahim on Youtube

Right after Mufti Ibrahim’s rumours, on the 8th of March, the first case of a patient infected with the Coronavirus was identified in Bangladesh. Since then the virus spread rapidly and finally, on the 26th of March the government formally announced a lockdown. For the general public, this meant that they became prisoners in their own homes. On the other hand, for the ‘cultural workers’ the lockdown signifies a tremendous threat, especially for those whose performance of traditional cultural genres represents their only source of livelihood. Folk artists in Bangladesh, despite being important creators and contributors to traditional culture, are not registered in an official list [as it is the case in the neighbouring state of West Bengal, India, TN] and hence they are not systematically helped by specific schemes for aid and social welfare, whether formal or informal.

Many of these artists continued to be productive during the lockdown. Among the artists whose creativity was not diminished by working from home, is Arif Dewan. Arif Dewan resides in the Keraniganj area of the larger Dhaka division. He definitely did not spend his quarantined time at home by being lazy. In fact, he composed 375 new songs. Apart from composing the lyrics and putting them into music, he has also performed some of the songs and shared them via Facebook and YouTube. Among these new songs, some are specifically about the coronavirus outbreak. They touch on these three themes in particular:

- He described the ways in which practitioners struggled with the impossibility of gathering (sadhusanga) for spiritual as well as music-making sessions with their teachers and peers. See for example the verses: Lokdaune achi bondi ghore bose kandi / sadhusonge kobe hobe milon / bhab bine bhaber manush bace na kokhon. (“I am imprisoned by this lockdown, I sit at home and cry / when will we meet again in the assembly of sadhus? / without that feeling of ecstasy the ecstatic men cannot survive for long”).

- He strongly condemned groups of dishonest people who plundered the resources that the government deployed as aid and relief during Covid times. See the verses: Khudarto manush jara kore ahot / bibek-hin manush ora nei manushotvo / onahari manushgulo kore ahajari / mukher khabar kere niya e kon rajniti kori / oder nei adorsho nei niti / dekhe nijer swartho. (“Humans whose actions hurt those who are hungry / inconsiderate people, these are not humans at all / they mock those who are starving / digging food out of their mouths / which kind of political action is this? They have no values or morals / they act out of selfishness only”)

- He describes the Coronavirus pandemic as part of the larger divine game of creation, destruction, and preservation. See the verses: Noirajyo durniti anite shrinkhol / tumi jaha koro probhu sokoli mongol / prokriti biponno manush manobotashunnyo / kore dhonsho koro purno, obicar nirmul koro jwalo dabanol (“Bringing discipline in a time of injustice and anarchy / whatever you do my Lord is always auspicious / Nature is endangered and humans are devoid of humanity / through destruction you bring fulfilment Lord / eradicate injustice, and burn like wildfire”)

Arif Dewan painted through his songs a social portrait of the coronavirus pandemic in Bangladesh which will be an important resource as a historical record for the future. Some of his songs can be found here or here.

Fig. 3. A picture of the composer Arif Dewan. Photo taken by Saymon Zakaria, 21 August 2020

Among the folk poets of Bangladesh many have composed long narrative poems in the traditional form of punthi centred around the Coronavirus pandemic. For example, a well-known Sufi practitioner and punthi poet of Manikganj district, Saidur Rahman Boyati, has composed an entire epic poem named Virus-nama punthi which narrates in a historical fashion previous pandemics and the reasons of their outbreak. The poem goes on to narrate in traditional metric patterns and verses (poyar, tripodi, choupodi) the rationale behind the attack of the coronavirus on Earth, and the ways to counteract the virus by nurturing purity in mind, body and social relationships.

Fig. 4.Saidur Rahman Boyati, during a performance of traditional Sufi music at Hasli in Manikgaj district. Photo by Saymon Zakaria, 3rd March 2008.

Apart from Saidur Rahman Boyati, a younger punthi composer named Punthi Mobarok in Jamalpur district has composed in a similar vein a complete punthi poem entitled Coronar Akromon [“The Attack of Corona”]. In his poem, he described in detail when and where the virus started to spread on the planet, giving an account of the situation in Bangladesh from the first appearance of Covid until the most recent developments.

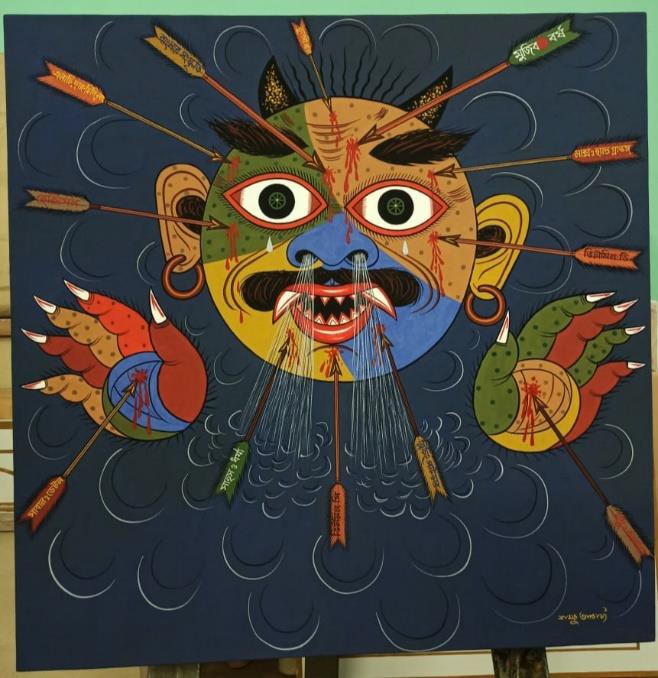

Folk artists who produce painted scrolls, called patacitra in Bangladesh also responded with innovations to the challenges imposed by the Corona pandemic. Shambhu Acharya is a famous painter from Munshiganj district (Bikrampur), and is well-known for his painted scrolls of Gazi characters (Gajir pat). In his recent creation, “The slaying of the Corona Demon” (Coronasurer bodh), the virus-demon has long sharp teeth and claws, a thick moustache and wide frightening eyes, donning a pair of horns and a pair of round earrings.

Fig. 5.“The slaying of the Corona demon” (Coronasurer bodh), a painting by Shambhu Acharya. Courtesy of Abhishek Acharya, sent to the author on the 21th of August 2020

The artist used traditional features of Hindu demonic characters to paint the face and the limbs of the demon Corona, pierced by twelve arrows. Each of the twelve arrows bears the name of a potent antidote or ingredient to defeat the virus. The painting is aimed towards spreading social awareness. Among the weapons that strike the demon-disease one can read: Dettol soap; Vitamin C; cardamom and cinnamon; sacred basil leaves; face mask and hand gloves; but also ‘Bengali culture’, courage, and righteousness. Besides these remedies, one of the arrows bears the name Mujib-borsho, the 100th birth anniversary of the father of the nation, Sheikh Mujibur Rahman, which falls precisely this year. The observance of this patriotic celebration is one of the arrows which defeats the corona-demon. The folk artist revealed that he depicted the coronavirus according to the folk songs that the painted scrolls artists composed to go together with the unfolding of their narrative images.

In sum, the Coronavirus pandemic, like catastrophes that have occured beforehand, triggered complex responses and transformation within the field of traditional cultural production. Artists have used their respective genres to reach the public but have innovated their contents to describe and interpret the coronavirus and the challenging social circumstances faced by Bangladeshis during the pandemic. Further documentation and analysis of these novel forms of cultural production is needed in order to understand the long term impact of Coronavirus on Bangladeshi traditional folk culture.

Disclaimer: The views and opinions expressed in this article are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the position of the blog editorial team or the Asia Research Institute.

South Asia | Southeast Asia | East Asia | Other Places | Hinduism | Buddhism | Islam | Christianity | Other Religions

Saymon Zakaria is a writer, researcher, and Assistant Director of the Bangla Academy, Dhaka, Bangladesh. He is internationally recognized for his ethnographic field-surveys that relate to Intangible Cultural Heritage. Among his books see Pronomohi Bongomata: Indigenous Cultural Forms of Bangladesh. He has delivered academic lectures on language, literature, and culture at several universities in the world. He was the recipient of Bangla Academy Literary Award 2019.