A Virus in the House of God: COVID-19 and Catholic Mass

contributed by Beverly Anne Devakishen, 8 October 2020

On 19 June 2020, Phase Two of Singapore’s circuit breaker began. COVID-19 restrictions were eased, and religious gatherings up to 50 people were allowed. The Roman Catholic Archdiocese of Singapore announced that Catholics could go to one weekend mass a month, starting from July.

It was National Day, 9 August, when my family and I were finally able to attend mass for the first time since February. My father confessed that his excitement had kept him up all night. I was unsure what to expect. I wanted to feel refreshed and relieved by the familiar feeling of attending mass. From the first moment I stepped onto the church grounds — when we were immediately ushered into a queue so volunteers could verify our identities — to the end of mass, — when we were told to leave by a certain door, six people at a time, were warned not to linger on the ground floor — I still longed for that feeling, that sense of familiarity and comfort. There was no normalcy restored, no semblance of a pre-COVID routine present.

Getting to attend mass again was a blessing and a privilege that made me happy. It was not, however, as reassuring as I had imagined it would be. COVID-19 had seeped into a sacred space, and it was unsettling to witness.

A short overview of Mass in Church

In the 1960s, the Second Vatican Council dismantled various barriers between the clergy and the people, transforming mass into the participatory and accessible service Catholics know today. This version of mass was built upon the traditional services that were performed in Latin. Many of the rituals performed, songs sung and prayers recited during mass were rooted in biblical practices first introduced by Jesus and his disciples. It was therefore essential that this service was carried out in what Catholic theologians call a sacred space or place.

In the Code of Canon Law, which is an official compilation of ecclesiastical laws for Catholics, it is stated that:

In a sacred place only those things are to be permitted which serve to

exercise or promote worship, piety and religion. Anything out of harmony with

the holiness of the place is forbidden.

Individual churches have imposed rules and guidelines over how a sacred space should be used and occupied. Some implement a formal dress code while others do not allow the use of cellphones inside. Eating and drinking are generally not allowed. These rules, coupled with liturgical rules of mass, help form the intangible boundaries of the sacred space.

COVID-19’s Visible presence

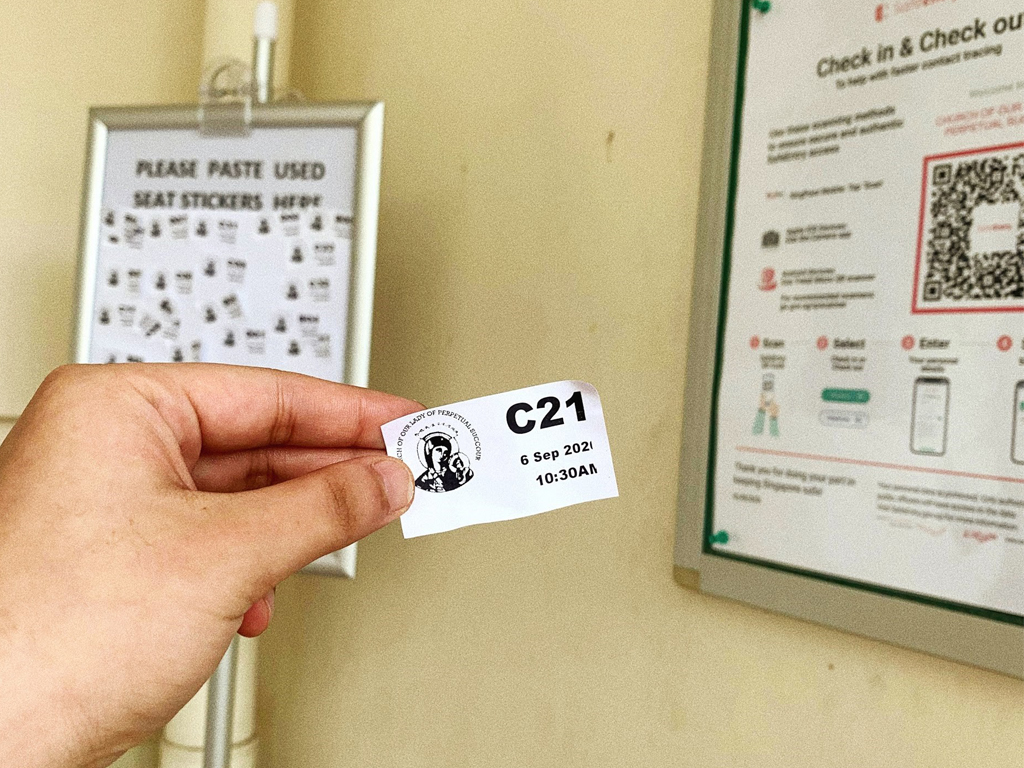

Physical signifiers of COVID-19 are visible from the moment a mass-goer steps onto the church grounds. Large sections of the church are closed off and the church is eerily quiet. One is immediately ushered into a queue and goes through several steps to verify that they had booked the correct mass online before coming. The parishioner receives a sticker with their seat number on it.

Fig.1. This is the sticker each parishioner is required to paste on their clothes. It shows your set number and the date and time of the mass that you are attending

While previously, mass-goers would sit together with friends, family and strangers alike; but now only two people per pew were allowed, each seated at opposite ends. There are squares on the bench that dictate where one is able to sit. Only once one is settled onto these strictly demarcated seats — temperature taken, mask on — can one begin to attend mass.

Fig.2. The green signs on the benches show you where you are allowed to sit. If you sit anywhere else on the pew, church volunteers will tell you to move back to the designated seat, even if you are sitting relatively close to the green sign and not directly on it

Adhering to measures to curb the spread of COVID-19 has become a precondition for attending mass. While previously, soft boundaries around the sacred space of mass in church were based upon what was deemed respectful in God’s presence, the rules of behaviour within this space have shifted radically to accommodate the conditions of the pandemic. Conforming to these newly instated rules is non-optional for those who wish to attend mass.

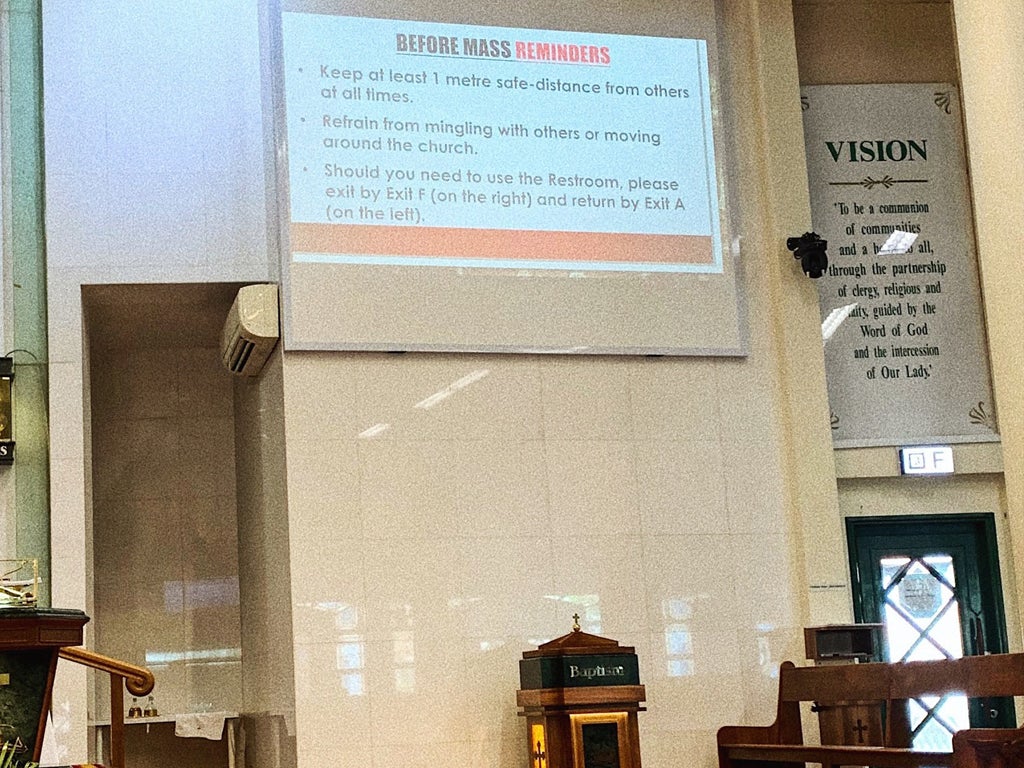

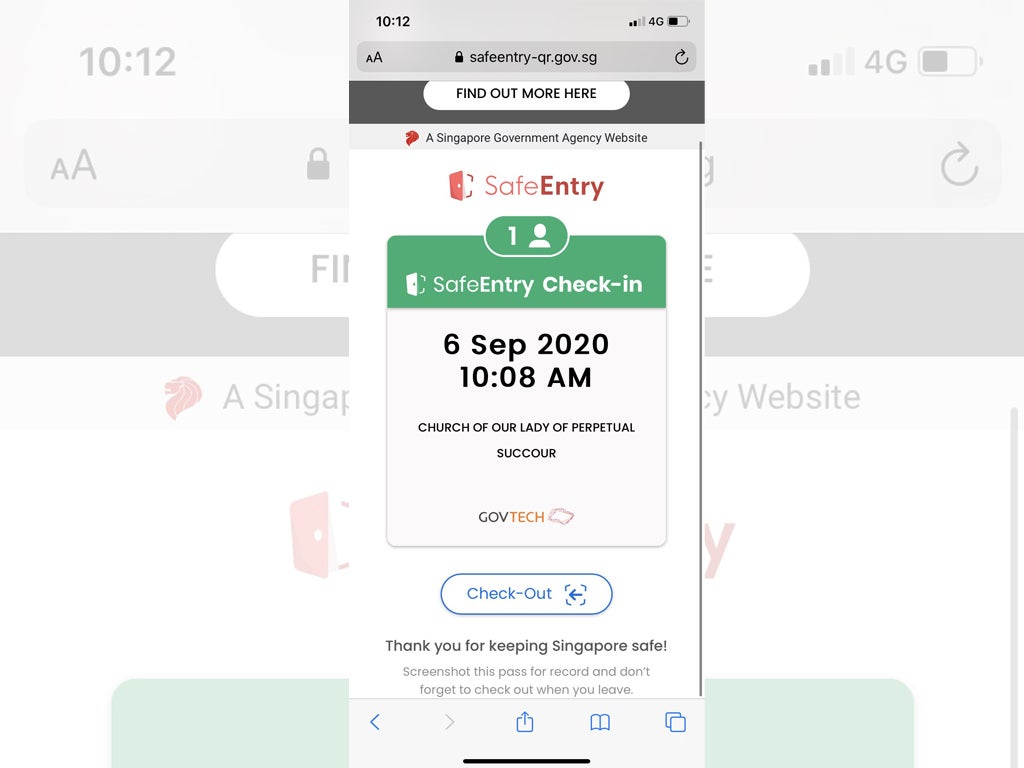

On the large screen, a PowerPoint presentation about COVID-19 restrictions flashes. Rules that were imposed on mass-goers were almost wholly determined by the Singapore government; for instance, in line with government guidelines, the church was obligated to prohibit singing during mass. On one slide, mass-goers are informed that the seat numbers and identities of those who sat in those seats would be submitted to the Ministry of Culture, Community and Youth (MCCY). SafeEntry data is also submitted to the government. This subtle and mild intrusion of the state into a sacred space is not surprising, as religious organisations have had to adhere to the Singapore government’s COVID-19 measures within their respective places of worship.

Since the late 1980s, religious organisations in Singapore have been held accountable to the state through legislation such as the Maintenance of Religious Harmony Act. The presence of state-sanctioned COVID-19 measures such as SafeEntry and the aforementioned instance of MCCY’s data collection serve as another reminder that the Catholic Church, for all its connection to a higher power, must still remain answerable to the Singapore government, and by association, to the wider Singaporean public.

Replacing old customs with medical safety

The PowerPoint presentation on COVID-19 restrictions, paired with an instructional video and an announcement, informs parishioners that singing is not allowed during mass anymore. Mingling with fellow mass-goers is also prohibited. While Communion was sometimes administered straight onto the tongue of the parishioner, new rules state that now it may only be received by hand.

Fig.3. This is one of the slides that mass-goers see before the service starts. An announcement containing these instructions is also made

Being in close physical proximity to other people and singing are two examples of bodily experiences that were an inherent, unquestioned part of attending mass. The prohibition of these familiar actions creates an immediate disconnect from the version of mass Catholics in Singapore have grown accustomed to before the pandemic happened.

There are also new actions that parishioners now have to perform during mass because of COVID-19. Aside from the requirement that everyone wear a mask, parishioners are required to sanitise their hands before receiving Communion. Sanitisers are placed along every alternate aisle, whereas church volunteers ensure that parishioners adhere to the santising rule: standing near the pews, they keep an eye on mass-goers and direct them towards the sanitisers before Communion is given by the communion minister or priest. Parishioners then have to step to the side, and facing the altar at the front of the church, pull their mask down to eat the Eurcharist before returning to their seats.

Parishioners have accepted these new measures and altered their Eucharistic routine. Masks and sanitisers have become a part of the bodily experience of going to receive Holy Communion. The physical space of the church, filled with stickers on pews and sanitisers, has changed alongside the community it houses.

COVID-19 and the Catholic faith

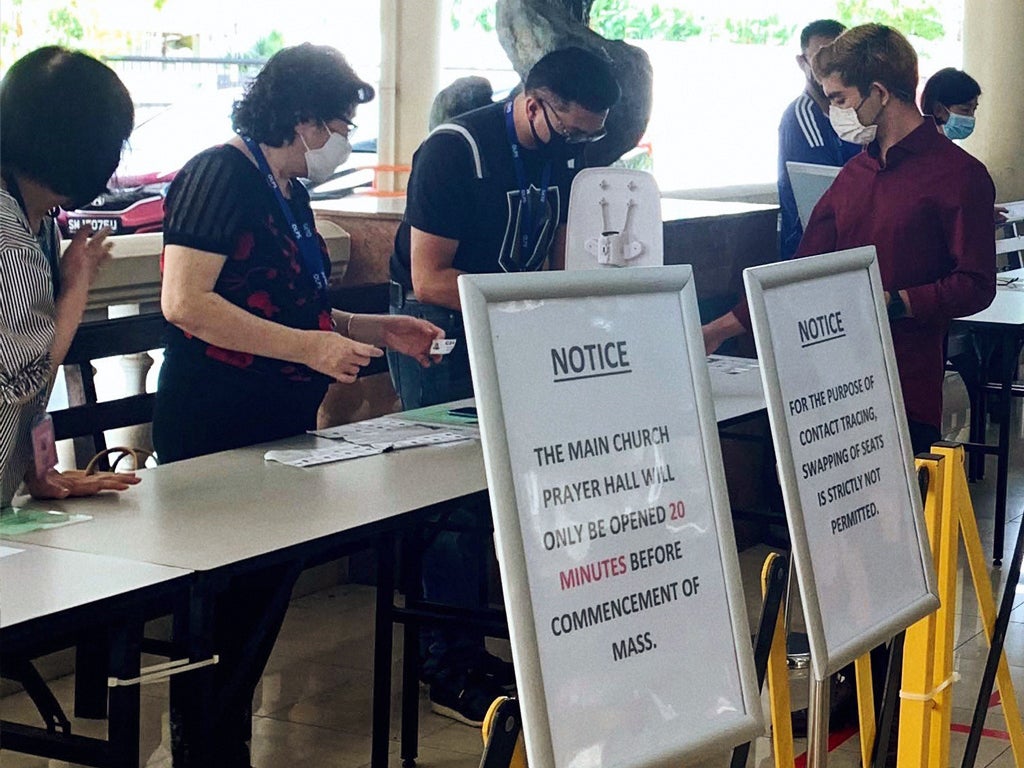

Fig.4. This is where parishioners are required to go when they first step foot on church grounds. Volunteers check your IC, your SafeEntry registration to confirm that you had made a booking for the correct mass, and then give you your seat number. A temperature check is also done on all parishioners

These COVID-19 measures are put in place to keep parishioners safe from the COVID-19 virus. The sacred space has been transformed, and the experience of attending mass has been altered. These changes are an acknowledgment that there is an external circumstance that cannot be negated through the power of prayer or worship. Science and religion collide in this space — fearing sickness and in some cases, death, Catholics sanitise their hands before receiving the Body of Christ, who, in the Bible, is resurrected from the dead.

The presence of COVID-19 within this sacred space, where an omnipotent, all-powerful God is worshipped, reveals the nuances and complexities within the modern Catholic faith. In the Bible, when Jesus was alive, people would come to him for healing. Curing them of various illnesses, Jesus would utter phrases such as ‘your faith has healed you,’ or, ‘your faith has made you well.’

Today, there is no steadfast belief that faith alone will guard one’s body from physical ailments. In its place is a quiet acceptance that ungodly phenomena will inevitably exist on earth alongside all things holy and godly. No healing miracles or the flouting of the laws of science are required to sustain the faith of a Catholic; in fact, we cannot afford to believe in this anti-scientific view of religion, especially during a pandemic.

Fig. 5. A SafeEntry screenshot from when I attended mass at Our Lady of Perpetual Succour

As I exited the church, longing for a pre-COVID-19 era, I discovered another feeling, buried deep down inside — hope. The Catholic Church is known to be inflexible and traditional. Yet somehow, I had seen the church and the mass transform before my eyes.

Witnessing the church changing to adapt to the pandemic gave me hope that, perhaps, the Catholic Church might be capable of changing alongside the rest of the world. COVID-19 was accommodated out of necessity and survival, and maybe in the future, change that happens out of love and care might be possible within the Catholic faith.

Beverly Anne Devakishen is currently working at the Department of Communications and New Media at NUS as a research assistant, and graduated with a Masters Degree from the Department of Southeast Asian Studies. She is also involved in starting up Eastsider Helpers, a mutual aid initiative in the East side of Singapore. You can find their Instagram @EastsideHelpers.

Disclaimer: The views and opinions expressed in this article are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the position of the blog editorial team or the Asia Research Institute.