Gods Have Eyes: Praying Online in Singapore

contributed by Alvin Lim, 29 May 2020

Going to church in the early 2000s, I was used to PowerPoint slides that were projected on a big screen, magnifying long scriptural passages and song lyrics—Arial font, size 14 to 16—for the congregation to read. In fact, I had the experience of reading aloud from the bible, on the pulpit, and behind me were those verses. By the time churches began to embrace live broadcasting and online streaming of their services, the still images of biblical words remain as a mode of presentation.

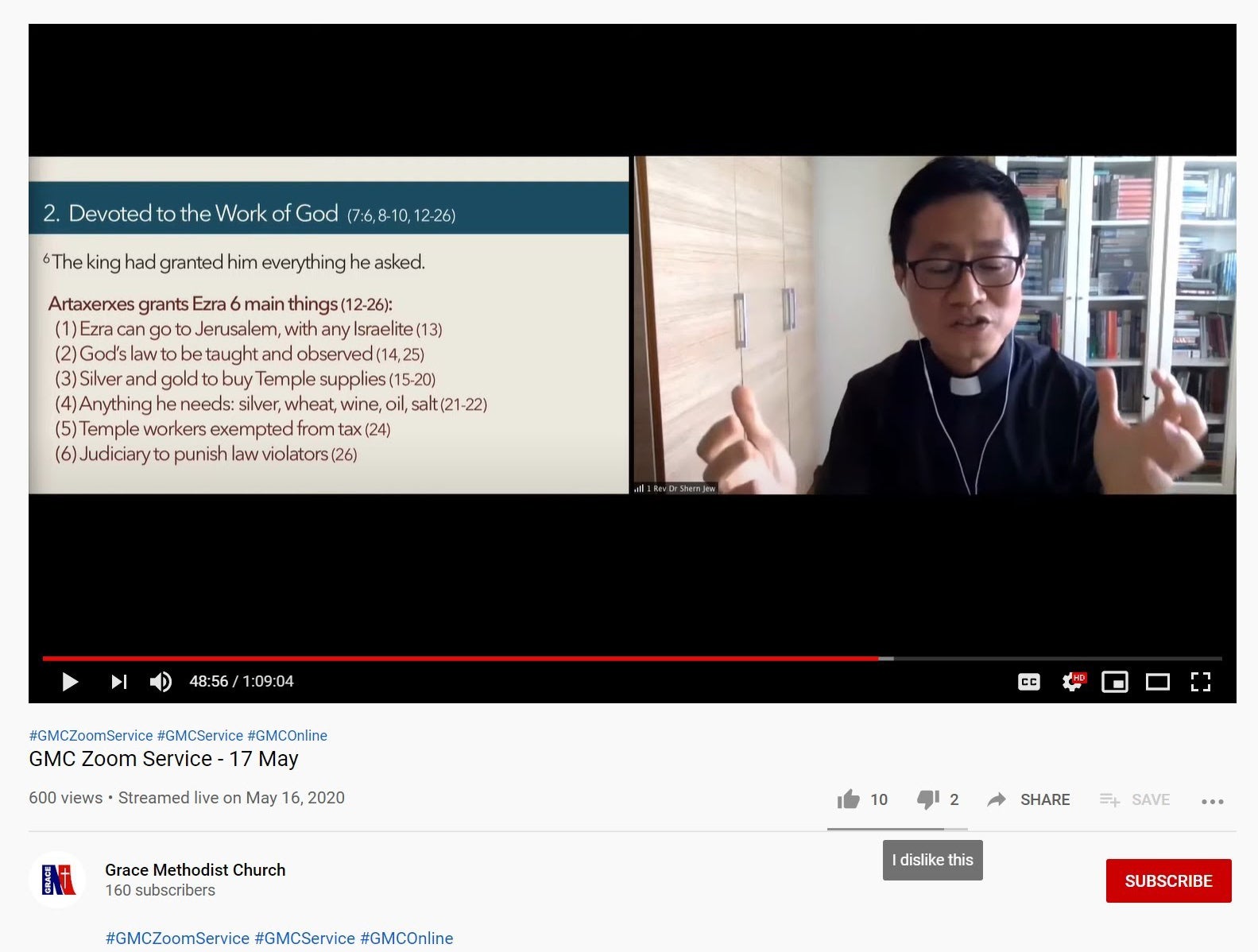

The Covid-19 pandemic has since compelled religious gatherings to move to online platforms. Some of these religious groups produced technologically advanced HTML5 websites to host and display their videos. While others turned to Zoom to host their church services. The easy-to-read slides persist, their cameras remain still throughout, and faces of church pastors and worship leaders are caught in a grid of sorts.

Screenshot of the recording of Grace Methodist Church’s “Zoom Service” on 17 May 2020, available on YouTube. Credit: https://youtu.be/efbI0kupTpc?t=1204

The Gaze of the Still Camera

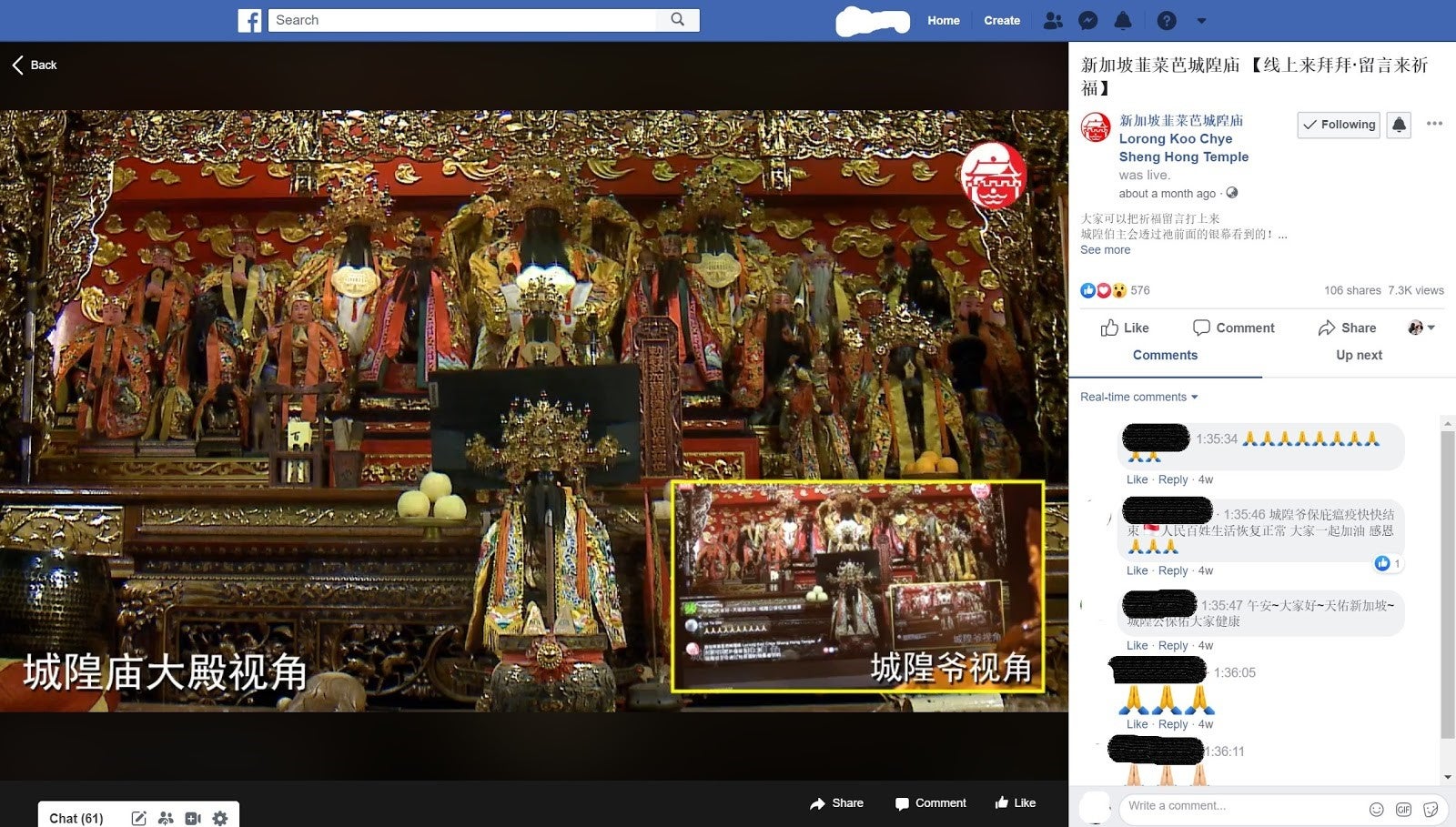

On 7 April 2020, Lorong Koo Chye Sheng Hong Temple (新加坡韮菜芭城隍庙) introduced the “Praying Online” initiative in response to safe distancing measures and the implementation of the ‘Circuit Breaker’ in Singapore. For two hours a day (10:30am to 12:30pm), devotees can go on their Facebook page to view the main altar of the temple and pray to the tutelary deity, Cheng Huang Gong (城隍公). Devotees leave online messages and emoticons (

Screenshot of Sheng Hong Temple’s Facebook video of Cheng Huang Gong and devotees’ prayers online, 21 April 2020. Credit: https://www.facebook.com/LKCSHENGHONGTEMPLE/videos/1131827440502825/

Who Is Looking At Whom?

Christian and Taoist online religious gatherings in Singapore seem to engage the ocular sense in a simplified way compared to their former offline practices. There are fewer things to view. The background is often someone’s room or private space; it can also be a virtual backdrop that creates an illusion of another place.

The use of the online platform and the mode of presentation mean that viewers look directly at the screen; the worship team, pastor or spirit intermediary look straight at the camera. They all perform for and with the screens. Instagram also shows that church congregations continue to engage with the screens by singing along during the worship segments.

Screenshot of Instagram posts that show the congregation of New Creation Church attending their service from the comfort of their homes. Credit: https://www.instagram.com/explore/tags/newcreationchurch/?hl=en

In the case of Sheng Hong Temple’s online Facebook live video, the deity—via the effigy—is believed to ‘see’ directly into the screen. Similar to ‘seeing’ offerings by devotees of oranges and flowers placed in front of the altar, deities can view them as acts of devotion without the need for them to physically be in attendance.

The live streaming creates the effect that the message will be read, in spite of the slight delay in the relay, and the act of devotion can substitute for the embodied practice of going to the temple. From a visual point-of-view, activities and gestures are kept to a minimal level such that there is still a simple engagement with the deity. That suffices.

In the Christian context, a different kind of religious expression takes place. During Christian services streamed online, pastors ask viewers to close their eyes to pray, while looking at the camera themselves, and to feel the presence of God. This perhaps echoes Roland Barthes’s notion that “in order to see a photograph well, it is best to look away or close your eyes” (53).

The Embodied Practice of Praying Online

In the face of social distancing measures, the use of the still camera and live streaming technology may very well be the most effective way to replicate the experience of going to church or to the temple. As much as they look ‘simple’, there is something profound in the proliferation of gods through a still image and the use of slides (the new trend is to use Google Slides). They are simple aesthetic choices but they can fill devotees with a nostalgia for the church hall, the temple altar, the human touch. If anything, the screens, with the camera looking directly at the focal point of devotion and worship, can help the viewer to ‘look away’ in order to see or experience god.

Screenshot of the recording of Grace Methodist Church’s “Zoom Service” on 17 May 2020, available on YouTube. Associate Pastor Rev Dr Ian Jew Yun Shern used the split screen function and slides as he gave his sermon online. Credit: https://youtu.be/efbI0kupTpc?t=1775

While they ‘look away’, the camera does the looking; the screen does the showing. The slides unveil the divine inspiration. In that sense, gods have eyes in the form of technology to see acts of devotion, even in digital forms.

At least, that seems to be implied by this presence of the camera and devotees are motivated to repeat similar acts of devotion in the comfort of their homes. They harness technology to return to the essential components of their public worship: the gesture of praying.

God Can Hear

While I have largely described the new modes of online worship by privileging the sight perception, the gesture of prayer can still be an intimate act. By closing one’s eyes, the subjective experience becomes an aural one, as one listens to the sound of the pastor as well as one’s own voice (inner or spoken aloud) praying in tandem with the pastor. A continual loop of Sheng Hong temple’s theme song also frames the encounter with the deity on Facebook live.

Sounds, then, directly percolate through the headphones to the ears of prayers. There is a sense that the voices and the sounds are being directly felt by the listener. That contributes to the intimate experience, or at least to a semblance of being in the presence of one’s god.

It is nearly three months since the closure of religious spaces in light of Singapore’s Circuit Breaker measures. But the still cameras, screens, headsets and speakers, and Whatsapp messages, remind the devotees that there is still a congregation to return to, a life of worship and devotion that must continue.

Alvin Eng Hui Lim is a performance, religion and theatre researcher. He is Assistant Professor in the Department of English Language and Literature at the National University of Singapore. His first monograph, titled Digital Spirits in Religion and Media: Possession and Performance (2018) studies how lived religious practices in contemporary Singapore perform in combination with digital technology.

Twitter: @dasparadies (https://twitter.com/dasparadies)

Disclaimer: The views and opinions expressed in this article are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the position of the blog editorial team or the Asia Research Institute.

South Asia | Southeast Asia | East Asia | Other Places | Hinduism | Buddhism | Islam | Christianity | Other Religions