The Sonic and the Somatic: Matua Healing Practices during COVID-19

contributed by Dishani Roy, Raka Banerjee, Carola Lorea, Fatema Aarshe, Md. Khaled Bin Oli Bhuiyan & Mukul Pandey, 22 January 2021

The disturbing times of COVID-19 have impacted the relatively unknown Matua religion and its devotees, especially their healing practices. As a religious and social movement suffering social wounds such as untouchability and displacement, the Matuas have historically deployed strategies of healing, not only in the medical sense of the term, but also within the framework of social upliftment, primarily in countering their caste-class oppression. Matua beliefs interrogate the assumed polarities of ‘body’ and ‘spirit’, ‘individual’ and ‘community, ‘science’ and ‘religion’, reflected in their ritual practices.

To understand how Matua devotees responded to the challenges brought about by the COVID-19 pandemic, our team of six researchers, with the supervision of Dr. Carola Lorea, conducted phone interviews and online ethnography with Matua participants based in West Bengal, Bangladesh and the Andaman Islands. This project is part of the larger study “Religion Going Viral: Pandemic Transformations of Religious Lives and Ritual Performances in Asia” conducted at the Asia Research Institute, National University of Singapore. While it is no easy task to explicate the many elements that make up Matua religious practices during the pandemic, this article will focus on the sonic and the somatic aspects of Matua ritual, as they are prominent characteristics of this distinct knowledge system.

The Matua community emerged in the nineteenth century in the marshy southern area of East Bengal (now Bangladesh). Matua faith derived from popular Vaishnava devotionalism, but it developed as a separate caste-based religious movement with the purpose of uplifting the Namashudra people (a lower-caste community) both spiritually and socially. Advocating for a materially-grounded philosophy focusing on worldly duties and responsibilites, founding saints Harichand Thakur and his son Guruchand Thakur condemned caste discrimination perpetrated by the high castes by emphasizing the dignity of labour and also the importance of unity and education. However, the Partition of undivided Bengal in 1947 disrupted the territorial unity of the Matua community, which is now scattered in several areas of the subcontinent. A large portion of the community migrated to India as refugees, where they are still struggling for citizenship rights. At present, leaders of the community believe that there are about fifty million Matua followers in India and Bangladesh.

Given the outbreak of the pandemic, all Matua rituals and festivities have been adjusted to adhere to governmental medical protocols. Matua leaders limited the use of social space for devotees, who would otherwise have participated in ritual congregations (hari sabhas, their devotional gatherings; kirtans, which are recitations of harililamrita - their sacred text which is a biography of Harichand Thakur - and many more events) in large numbers. The period between December to March would have normally been full of vigour, from planning local festivals (the 3-day mahotsab) to preparing for the major Matua pilgrimage and ritual gathering, named baruni mela. Instead, all this is now marred by the uncertainty of the pandemic. The annual pilgrimage to the guru’s homeland(s) was cancelled this year, together with many regional mahotsabs. But despite the cancellation of these mass gatherings, the Matuas seem to have reworked their foundational beliefs and devised newer strategies to combat physical isolation and yet still ensure communal unity.

Sonic Healing: Aural-Oral mediations online

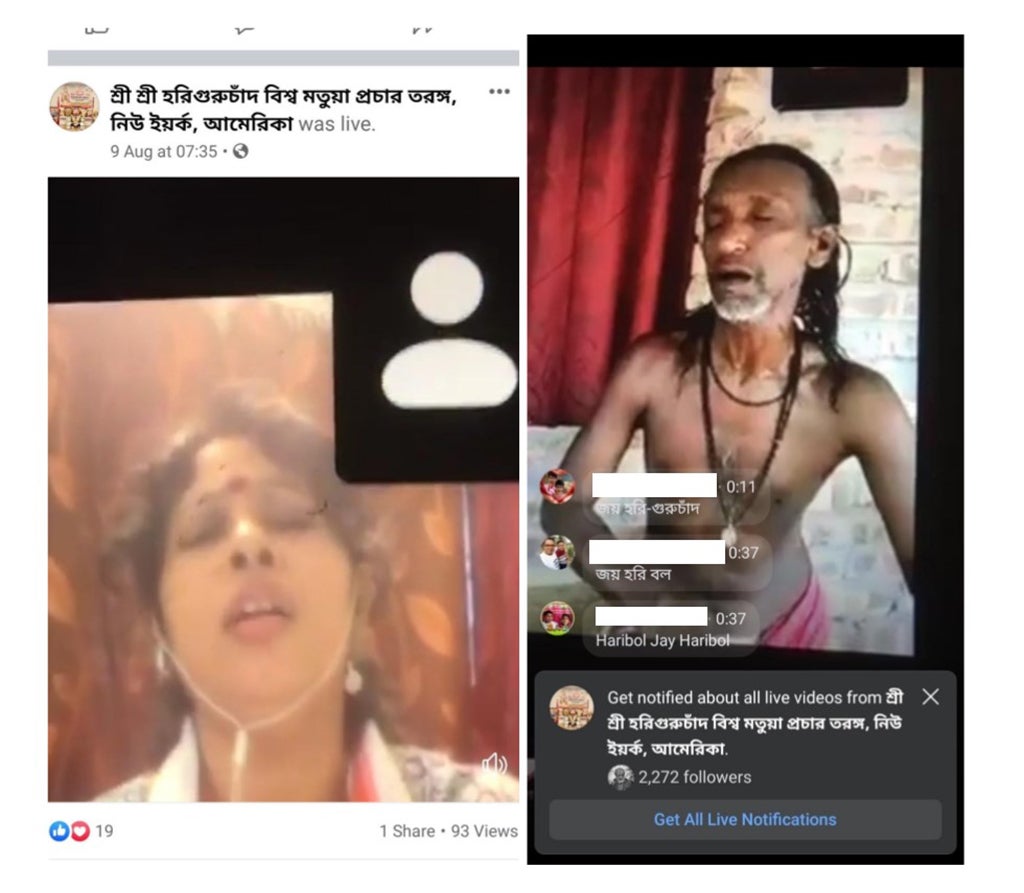

As a community, the Matuas believe in the sonic potential of devotional togetherness in the form of kirtan (singing in praise of the Lord) sessions and collective chanting of haribol (uttering Hari, the Lord’s name) in ritual gatherings. Since the beginning of the lockdown, Matua leaders and Gosains (spiritual healers) have recommended that followers sing kirtan and perform mataam (a ritual dance that is said to impart spiritual and physical strength) - believed to help build stronger immune systems - to keep the virus at bay. However, the pandemic-induced lockdown and health guidelines prohibiting large-scale assemblies have oftentimes resulted in shifting of congregations like harishabhas to online spaces, augmented with occasional small gatherings. The online activities, which have increased since March 2020, incorporate not only religious and political discussions by devotees but are also instrumental in conducting group prayers and arranging kirtan sessions. Participants of these new Matua assemblies and talk-shows over Zoom are present both as co-speakers/singers or simply, as audience members, typing in ‘Joy Horibol’ [hail to the name of Hari] in the comment sections and via chat. The need to reproduce connection and togetherness in cyberscape is demonstrated by the fact that a number of new Matua Facebook pages and groups arose, including a global platform for Matua migrants settled in 35 different countries. What was earlier a bodily experience of praying together has now been readily taken up by online platforms like Zoom ‘rooms’, uniting people across space and time by igniting devotional consciousness but yet, at the same time, isolating them from their conventional modes of collective devotion. YouTube channels like this one have come up during the pandemic, with its aim to ‘propagate and teach the true scriptural devotion of all religions and to free the society from superstition.’

Fig. 1. (left) Screenshot of a female Matua devotee singing devotional ‘kirtan’ at a Facebook live event hosted by the account ‘Sri Sri Hariguruchand Bishwa Matua prachar Taranga, New York, America’, an international Matua organisation based in the USA, dated 9th August 2020. (right) A male devotee singing ‘kirtan’ at another Facebook live hosted by the same account and fellow devotees can be seen commenting by typing ‘haribol’ on the live chat

Figure 2. Female Matua devotee singing ‘harisangit’ from her home, hosted by the Facebook page ‘SriHari- Guruchand Matua Mancha’ and ‘Matua Barta’

Usually, Matua gatherings are highly sensory experiences of haptic and sonic communion, where collective crying, hugging, and touching each other’s feet are fundamental ritual gestures. But after the pandemic-induced shift to online platforms, in these disembodied versions of praying, the bodily manifestations of affective effervescence like hugging and crying with each other are absent. Therefore, the Matuas resort to the kind of ‘healing’ achieved through spiritual awakening in participating in online sessions, as opposed to physical spaces reverberating along the rhythms of various instruments, singing voices, and dancing bodies. Some Gosains too have felt a compelling urge to impart diksha (initiation) over phone calls, while preaching organizations (prochar shongho) have created new Youtube channels to upload Matua sacred music (Harisangit) so that followers do not feel detached from themselves and their community at large. Moreover, uploading videos from past gatherings has enabled devotees to find comfort in nostalgic returns to pre-pandemic times. Watching these videos, including Facebook live-streaming of domestic ritual singing, and participating in such modes of ‘doing religion online’ opens a space for sonic purification of the devotee’s spirit, which in turn produces a healing effect on the devotee and the community.

Therefore, we see a trajectory of COVID-induced responses that spans over various arenas but are united by the common thread of devotion. Even in the political sphere, we see live broadcasts of rallies and processions for citizenship rights in various parts of West Bengal, India, which try to mobilize Matua followers and assert Matua unity for political rights.

Figure 3. Minister of Parliament (MP) Shantanu Thakur, who is a direct descendant of the saintly dynasty, presiding over a political event (Bagula Chalo, 19th November, 2020) for claiming citizenship rights for Matua people, published in his personal Facebook account

Figure 4. (left) Screenshot of MP Shantanu Thakur speaking at the same event, photographed and shared by the Facebook page ‘Matua Barta’. (right) A poster for a political rally (Shilinda Chalo, 22nd November, 2020) supporting the extension of equal citizenship rights to Matua ‘refugees’, shared by Shantanu Thakur on his Facebook profile

Online activity, as it seems, begins from individual participation and necessarily arrives at communal integration. The situatedness of Matua devotees in their homes is made public through web-cameras and their engagements on social media. These digital platforms help the community members to heal from diseases either of the spirit, the society, or simply, of the body.

Somatic Healing: Scientific cures and devotional remedies

The imposed restrictions on collective celebration, coupled with actual anxieties regarding the coronavirus, had an impact on the corporeal self of Matua devotees. The Matua prescriptions in managing infection range from using local herbs to observing ritual healing practices through highly energetic dancing and listening to rousing devotional music. What is uniquely common to both, as it is for most Matua practices, is a language that explains these phenomena with the vocabulary of scientific rationality. Interlocutors in Bangladesh, West Bengal and the Andaman Islands, are keen to balance the ‘scientific’ with the ‘religious’ – for instance, using face-masks except during mataam or harinaam sessions; suggesting plant-based remedies for illnesses; performing vows (manot rakha) for the speedy recovery of sick persons and sanitizing their hands regularly. Gosains are summoned for guidance in healing - a need especially heightened during the pandemic - and they advise devotees by prescribing a plethora of remedies: reciting particular sections of the sacred scripture Harililamrita printed in 1916; consuming a pinch of holy soil of Thakurbari (where the founding gurus or their descendants have lived) mixed with water; drinking the water consecrated in the ritual pitcher (ghat) or water from the sacred pond of Thakurbari where devotees bathe on the occasion of the annual Baruni Mela; and making a monetary contribution to Thakurbari in the name of Harichand Thakur. The Gosains affect the individual devotee’s body by prescribing dietary changes and intake of medicinal plants, like eating fermented rice (panta bhaat) with green chillies, chewing on tulsi leaves to keep the respiratory system strong, or drinking the juice of kalmegh leaves to treat fever. These measures, however, work in conjunction with healing prayers and singing of salvific songs. For instance, interlocutors pointed out that the chanting of Harililamrito passages had helped Matuas get rid of epidemics in the past like cholera, and this should be used to prevent the spread of COVID-19 as well - evidenced here where a child recites the cholera passage from Harililamrita to protect the Matua community from the Coronavirus.

Furthermore, interlocutors across the subcontinent who were interviewed for the project, consider COVID-19 as an urban disease. According to their understanding, rural Matuas are hard-working people with stronger immune systems than their urban counterparts and moreover, their devotion in Harichand and Guruchand Thakur is believed to protect them from the disease. It should also be pointed out that the unavailability of the prescribed herbs and concoctions in the urban areas, coupled with the diminished significance of traditional knowledge systems in the face of biomedicine, act in furthering perceptions of the ‘rural-urban’ divide in faith and protection from disease.

One of the key elements of Matua practice is ‘matam’, a ritual dance bringing to enlightenment. This is essentially performed in congregations, as a collective of devotees (even if just a few family members) and is considered an excellent form of physical exercise or dynamic yoga that helps them stay fit. A female Gosain, presumably in her fifties from Jessore, Bangladesh, repeatedly asserted the physical benefits of ‘matam’: “Matam kirtan is like physical exercise. If they do this, they will sweat all over their body. Because it is such a strenuous activity that helps build better immunity, corona won't be able to infect them." It is believed that whoever chants the name of Hari and performs matam will not be infected by COVID-19 because it acts as a cleansing ‘physical labour’, hence strengthening the immune system and making the mind calm and absorbed in ecstasy. In these 'prescriptions' by preachers and community leaders to increase the regularity of matam sessions, we encounter abundant medical jargon to legitimize this practice, more so in the face of this pandemic. For example, years before the COVID-19 pandemic, one of Dr. Carola Lorea’s informants in Ramdia (Bangladesh) mentioned that the sound of the large drums played during Matua kirtan sessions is able to kill the germs and defeat diseases through its loud vibrations and healing frequencies. Therefore, spiritual and bodily training towards self-realization (sadhona) simultaneously works to cleanse and purify the body, mind and soul. Building immunity, self-preservation, and communal health through these ritual practices are equally important during the pandemic.

Given so, not performing matam together as a result of following protocols against mass gathering in close proximity is considered to adversely affect devotees. For instance, Subrata Thakur, who is a powerful Matua community leader and local politician in Bangladesh and a direct descendant of the founding saints, contracted the coronavirus back in June. Some interlocutors believed that he had contracted the virus because the members of his saintly dynasty – the descendants of Harichand Thakur – do not perform matam, while others assumed that because of his political role as sub-district chairman he has been exposed to white-collar people from the cities, where the virus is believed to proliferate. The community responded in ambiguous ways when Subrata Thakur refrained from allowing the annual festival Baruni Mela (late March) to take place at the holy place – which is also his ancestral residence – following administrative orders to prevent gatherings. The sudden cancellation of Baruni Mela, which is the second largest religious gathering in Bangladesh, no doubt raised controversy. While on one hand several members of the community believed that obeying the protocols was part of their civic responsibility, some read it as an imposition on their religious and spiritual expression. Some devotees insisted on conducting the annual pilgrimage at any cost, circumventing police surveillance by taking longer foot routes across the fields. In their perspective, it is unfathomable that one might catch a disease in the place where one should annually go and take a ritual bath to stay free from diseases. Thus, we see how the Matuas negotiate their knowledge system to fluidly accommodate the need of the hour.

Praying and healing together

In conclusion, this article has chronicled the multifarious ways in which the Matua community has responded to the COVID-19 pandemic both spiritually and corporeally. Sonic and somatic healing practices, which are integral to Matua faith, have become magnified during the pandemic. These rituals are devotional in nature but are described with scientific logic. For a community that believes in the intersectional dimensions of corporeal, spiritual and social healing, the COVID-19 pandemic has only affirmed their pragmatic devotional practices, both online and offline. United by faith, individuals’ rituals, whether singing and dancing in small groups or live streaming from their homes, amalgamate to usher communal healing and collective well-being.

Disclaimer: The views and opinions expressed in this article are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the position of the blog editorial team or the Asia Research Institute.

South Asia | Southeast Asia | East Asia | Other Places | Hinduism | Buddhism | Islam | Christianity | Other Religions

Dishani Roy has recently graduated with a BA degree in Sociology from Presidency University, Kolkata, India. Her research interests include religion, caste and untouchability in South Asia, with a specific focus on what implications they have on the spirit, body and the society at large.

Raka Banerjee is a PhD research scholar at the Tata Institute of Social Sciences, Mumbai, India. Her research interests include gender, migration and oral history with a specific regional focus on South Asia.

Carola E. Lorea is a scholar interested in oral traditions and popular religions in South Asia. She is currently a Research Fellow at ARI, NUS. She received research fellowships from IIAS, Gonda Foundation (Leiden) and SAI (Heidelberg) to study travelling archives of songs in the borderlands of India and Bangladesh. She authored several articles and books, translated the works of Bengali poets and novelists, and serves as volunteer interpreter for Bangladeshi refugees and migrant workers.

Fatema Aarshe is a B.S.S student in Department of Anthropology, Jahangirnagar University, Dhaka, Bangladesh. Her research interests include working with social, political and cultural interactions as a way to understand diverse human life.

Md. Khaled Bin Oli Bhuiyan received his bachelor’s and master’s degree in Anthropology from Jahangirnagar University, Dhaka, Bangladesh. He is particularly interested in the interplay of colonial hegemony and biomedical discourse in the construction of body, and trying to develop analytical skills and knowledge to understand health, society, and culture.

Mukul Pandey is a graduate student in Sociology at Presidency University, Kolkata, India. His research interests are in the area of agrarian studies, development and rural economy.

Other Interesting Topics

Religious Response To The Pandemic Among Bengali Hindus In West Bengal: A Survey

In this survey I look into the everyday religious performances of people belonging to various Bengali Hindu communities during the current global COVID-19 pandemic. In this situation where the world seeks healing on a large scale, I seek to infer the religious responses

Coronavirus, Cults, and Contagion in South Korea

The skin plays a fundamental role in social relations, as captured by the Korean term “skinship.” Our skin helps to define us as individuals, but it is also a threshold (Eliade 1957). It is simultaneously a boundary of our bodies and a medium for communion with anyone—or anything—outside of them (Montagu 1971)

Impact of COVID-19 on the Life of Urban Buddhists in Thailand

COVID-19 is no doubt a huge global health crisis. According to WHO, Thailand was the second country after China to have registered a COVID-19 case. Buddhist monks and local temples play a central role in towns and villages across Thailand. Monks engage with the community on a daily basis, while temples