The Cap Go Meh that Never Happened (2)

contributed by Emily Hertzman, 7 April 2021

Figure 1: Temporary Gate Entering Singkawang for Chinese New Year and Cap Go Meh 2021

On February 21, 2021, the final meeting between the Singkawang city government and the religious councils was planned regarding the holding of Cap Go Meh this year marked by the global COVID-19 pandemic. That meeting was postponed to February 22, because the mayor had to go to Jakarta to receive an award from the Setara Institute for being the second most tolerant city in Indonesia. Singkawang is down from first place, a title it held last year, and the suspected reason for this drop is a case by a local Muslim group who accused a Chinese Indonesian citizen of religious blasphemy.

The meeting was attended by the mayor of Singkawang, as well as representatives from the police, the army, the Chinese Cultural Customary Council (MABT), the Indonesian Confucian Council (MAKIN), the Three Teachings Community (KBUT), the Indonesian Daoist Council (MTI), the Indonesian Buddhist Three Teachings Council (MAGABUTRI), and the Three Teachings Places of Worship Association (PTITD). Absent were the Assembly of Three Teachings Clergy Indonesia (MARTRISIA) and the Dayak Customary Law Council (DAD). At the meeting, a Collective Agreement was signed by the aforementioned parties during a press conference in which its contents were announced as follows:

- On February 26, 2021, the day of Cap Go Meh, the Festival will not be held in the city of Singkawang as it is normally held.

- There will not be convoys of spirit-mediums, dragons and lion dance troupes or the like - including no sedan chairs, instruments or entourages that might attract a crowd.

- Religious rituals are still permitted to be carried out by spirit-mediums and religious specialists, especially on February 25, 2021, the 14th of the 1st lunar month of the Chinese year 2572, but only at each respective altar, small temple, or Buddhist temple and in accordance with the COVID-19 health protocol.

- Rituals held on Cap Go Meh, Feb 26th, 2021 by ritual specialists can only happen at each respective altar, small temple, or Buddhist temple; in compliance with the COVID-19 health protocol and must end by 11:30 am.

- Members of the public are encouraged to pray in their homes and local areas only.

The Collective Agreement constitutes a compromised solution to the issue of the legality of regulating Cap Go Meh given its ambiguous and multi-dimensional nature as a public ritual and cultural performance. Emerging just prior to Cap Go Meh and during the two days of the event, was the tricky issue of sounds during the ritual. From the perspective of outsiders, the soundscapes that surround the ritual activities of individual spirit-mediums, as well as Chinese temple ritual practices, might seem like merely decorative, festive or entertaining elements. However, as many spirit-mediums and expert practitioners will explain, the music and sounds are NOT simply for entertainment, but are an essential form of sacred communication that helps to call the gods into presence. Prohibiting the use of drums, cymbals, bells, and gongs was an affront to many spirit-mediums, including two leaders of well-known spirit-medium associations, who complained vocally on Facebook about this prohibition. In response to this contestation, representatives of the police sought information about these dissenting individuals from one of the representative groups which manages spirit-mediums, adding to an already anxious atmosphere in the lead up to this event - a further layer of fear and uncertainty regarding how ritual activities would take place and be policed.

Figure 2. Chinese New Year and Cap Go Meh decoration, Singkawang, 2021

On February 25, 2021 (the 14th of the 1st lunar month of 2572), which is the main day spirit-mediums perform the ritual cleansing of the city streets, one group of spirit-mediums, led by one of the dissenting voices, conducted rituals using sound and music. Although no large crowds formed, the police were promptly informed and proceeded to give warnings. In the evening, the Cap Go Meh Committee set up a three-tiered altar at the Central Temple to honor the Jade Emperor (Hakka. Nyuk Fong Song Ti). The area was cordoned off, had a hand washing station, temperature inspection and bottles of hand-sanitizer. Worshippers were directed to queue up in order to enter and exit the temple in a circular direction.

Figure 3. Temporary three—tiered outdoor altar at Central Singkawang Thai Pak Kung and hand washing station at Fab Zhu Kung temple

The following day, February 26, 2021, after months of anticipation, the streets of the city were calm and quiet, with no signs of the usual enormous spirit-medium procession. A few individual spirit mediums roamed freely around the city on foot and without any entourage, with a handful of them ringing bells in minor violation of the mutual agreement. On the outskirts of the city, on Jalan KS Tubun, in Roban, and on Jalan Dwi Tunggal, there were incidences of spirit-medium “attractions” involving music, sound and performances of self-mortification. Although noisy, these ritual acts did not attract a crowd and hence were tolerated by the police.

This year Cap Go Meh fell on a Friday, the most holy day of the week for Muslims. In Indonesia, as a Muslim Majority country, there is an unwritten rule that other religious activity should not disturb Jumatan, or the Friday mid-day prayers. This is particularly the case locally in Singkawang, where great effort is always taken to ensure that no loud sounds or disturbances are made on Fridays, including the cancellation of previous year’s spirit-medium procession when they fall on a Friday. This year was no different. Although the ritual activities were small and took place at individual altars and temples only, it was still mandated that everything cease at exactly 11:30 am in order to respect Islam and the city’s Muslim worshippers.

The year 2021 also produced a dilemma for me, as an ethnographer who has been documenting Cap Go Meh in Singkawang for a decade. I had to balance, on the one hand, the desire to go and witness and document the event, but on the other hand, the desire to not inadvertently contribute to crowding or put myself and others at risk. Ultimately, I chose to go out for my usual afternoon walk, but with no particular destination in mind, deciding that if I witnessed anything, I would record it, but I would not attempt to visit places that could be crowded. Here are some images from my walk that day:

Figure 4. Spirit-mediums’ sedan chairs (Hakka. to khiao) in front of house temples

Figure 5. Spirit-Mediums on the street

Figure 6. Temporary outdoor altars

Figure 7. Ghost writing to activate talisman at a house temple

Overall, I felt surprised, a little bit sad but relieved to find that very little activity was taking place - showing a strong adherence to the Collective Agreement. As I wove through the small side streets moving from the center of the city to the outskirts of town, I was struck by the quietness and the sense that this was just any other day. It was a stark contrast from all other years, in which Cap Go Meh has had some of the tightest, hottest, loudest, smokiest, and most intense incidences of crowding (Indo. keramainan; kerumunan) around ritual possessions. On my way home at dusk, I rounded a corner near a friend’s temple and saw a small group of people scattered around the grounds in anticipation of spirit-medium visits. There was one medium in trance who began to perform acts of spiritual strength by dragging blades across his flesh, while dancing. Motorcycles began to stop and people began to gawk. A crowd started forming in a circle around him, and many onlookers began to make video recordings, including myself. Seeing how quickly the crowd formed I was reminded of the importance of being there and present to witness something that is one of the backbones of anthropological methods, which is as significant to the locals as well. This witnessing is a major past-time and entertainment especially for the local Chinese population, and acts as a powerful legitimation of the presence of the gods in local communities and produces the sacred geography of the city.

Video: Spirit medium in trance (credits to author)

Cap Go Meh is usually the most intense, dense and potent annual ritual in which the prescensing of the Chinese and hybrid-ethnicity deities takes place; it is no surprise that the scale of the event has the ability to draw a huge crowd. I could feel, in this year’s Cap Go Meh, that such a process never happened. Instead, I witnessed the absence of that monumental moment of sacred activation of space and community in relationships with the gods. As I watched people pass by the temple and slowing their footsteps down to watch, I wondered if others also felt this absence. In my informal chats with locals it was clear that they also felt the same way, with most hoping for a return to the old ways of celebrating next year.

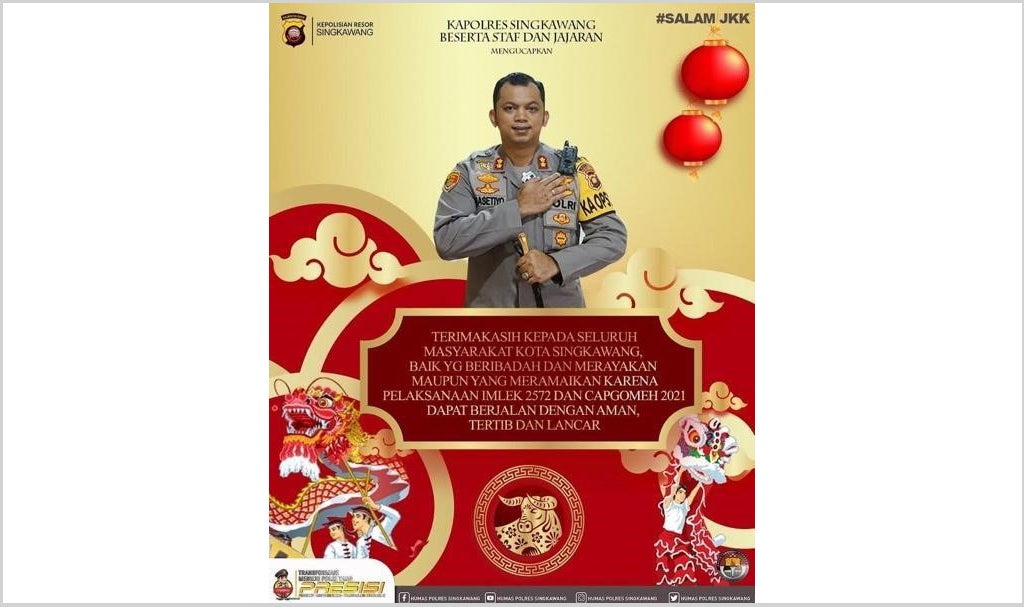

Figure 8. Thank you poster from the police to the citizens of Singkawang

The following day, Lo Mau Sui Kheu Pak Kung Temple held a ritual to officially open a newly built temple, place and activate the gods’ statues on the new altar. The atmosphere was calm, the ritual ran smoothly and complied with health protocol. That same day, the Singkawang Police Chief made a statement expressing gratitude from his police and staff to the worshippers and the Singkawang community for the success of carrying out the 2021 Cap Go Meh ritual in accordance with the Collective Agreement. This official statement, as well as a poster that was circulated on social media provided closure to the event, and had the effect of softening the tensions that had mounted surrounding the polemic of regulating and policing Cap Go Meh as either a religious ritual or a cultural tradition. We can read the success of this “Cap Go Meh that never happened” as another feather on the cap of the second most tolerant city in Indonesia.

Disclaimer: The views and opinions expressed in this article are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the position of the blog editorial team or the Asia Research Institute.

South Asia | Southeast Asia | East Asia | Other Places | Hinduism | Buddhism | Islam | Christianity | Other Religions

Emily Hertzman is a sociocultural anthropologist whose research focuses on Chinese Indonesian mobilities and identities. She received a B.A and M.A. from the University of British Columbia and a Ph.D. from the University of Toronto (2017). She will be joining the Asia Research Institute in the Religion and Globalization cluster at the National University of Singapore as a Research Fellow in 2021.