The Transformation of Temple Operations in (post-) COVID-19 China

contributed by Chen Ningning, 6 May 2021

Cover image: City God Temple (chenghuangmiao, 城隍庙) in the city of Lufeng, Guangdong Province. Taken by the author

This blog post documents preliminary research findings on the reconfiguration of temple operations in (post-) COVID-19 China, which is part of a collaborative research project titled ‘Religion going viral: Pandemic transformations of religious lives and ritual performances in Asia’.

To conduct research on religion and COVID-19 in China, I have selected Teochew regions in Guangdong Province, southern China for fieldwork. Specifically, two townships (Donghai Township and Hexi Township) in a county-level city of Lufeng, and three villages (Xia Village, Heping Village and Qianyan Village) in Shantou municipality are included. Most residents in these rural townships and villages participate in local communal religion and worship a variety of temple gods, many of which are of local origin. On occasions such as the first and fifteenth day of each lunar month, the birthdays of temple deities, the first days of Chinese New Year, and the Hungry Ghost Festival, people visit temples and perform rituals: providing offerings, lighting incense and candles, burning incense paper, and praying for the good health and prosperity of their loved ones. These acts are followed by the practice of dropping divination blocks at the temples to get divine predictions on their health, wealth, work and marriage situations.

The COVID-19 pandemic has profoundly reshaped the landscape of local communal religion in Teochew areas. This is visibly evidenced by the transformation of temple operations.

Generally, the opening hours of local temples during the pandemic is decided by both the government and temple committees. On the one hand, given that religious gatherings have the potential to cause widespread viral transmission, the local government is responsible for formulating relevant policies and regulations with respect to religion in order to bring the local COVID situation under control. On the other hand, village temples in Teochew regions are locally funded, organized and managed. In most cases, local village committees have cooperated with the local government and followed their guidance. Yet, they also have a certain autonomy to decide to what extent local temples are opened up for ritual performance, especially when there have been no new cases for a while.

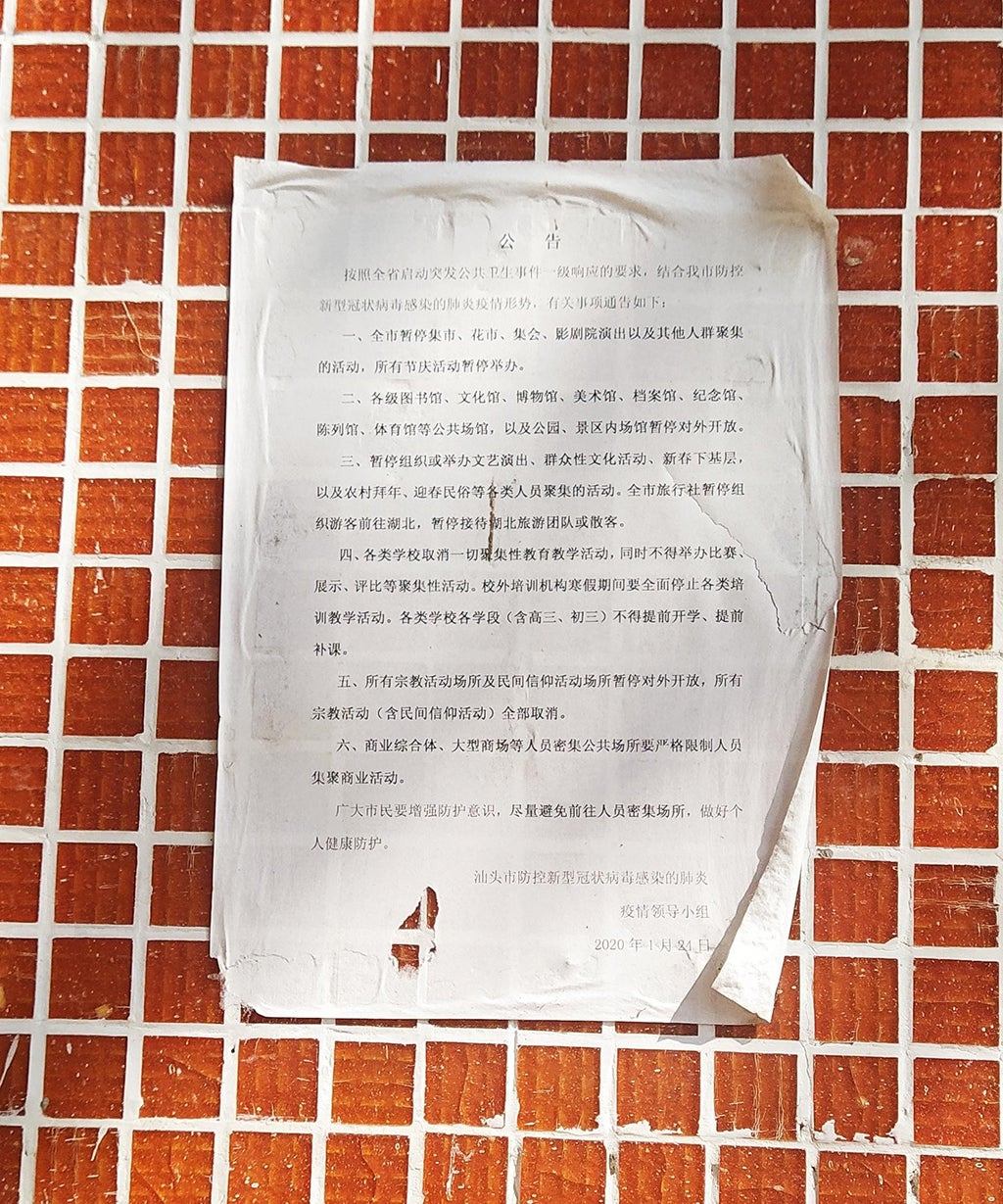

During the COVID-19 outbreak which began in late January 2020, the governments in Lufeng and Shantou ordered all local temples to suspend their activities and operations (see Figure 1). They also established patrols to monitor the area around temples, which made it almost impossible for locals to conduct on-site temple rituals.

Figure. 1. The state notice about the suspension of temple and other socio-cultural activities during the COVID-19 outbreak

When it came to the post-COVID period, the conditions regarding temple operation in these regions can be divided into the following phases. The first was roughly from May to July, 2020. During this period, many socio-economic activities resumed. Yet, religious activities were not classified as essential, so local temples were still awaiting further government directives regarding reopening. Some local temple committees and caretakers sympathized with local believers in not being able to perform temple rituals for such a long time. As such, upon requests from the local devotees, they secretly opened up the temples’ side doors in the early morning—usually between 6am and 8am, before patrols came. This was made possible because the local government had loosened their control and only sent patrols to monitor the area around temples during the official hours.

The second phase was generally characterized from late July, 2020 to mid-Jan, 2021. The local government permitted the re-opening of all kinds of village temples, and also the resumption of ritual performance therein. Yet, large-scale ritual events such as the Gods’ procession were not allowed to be organized.

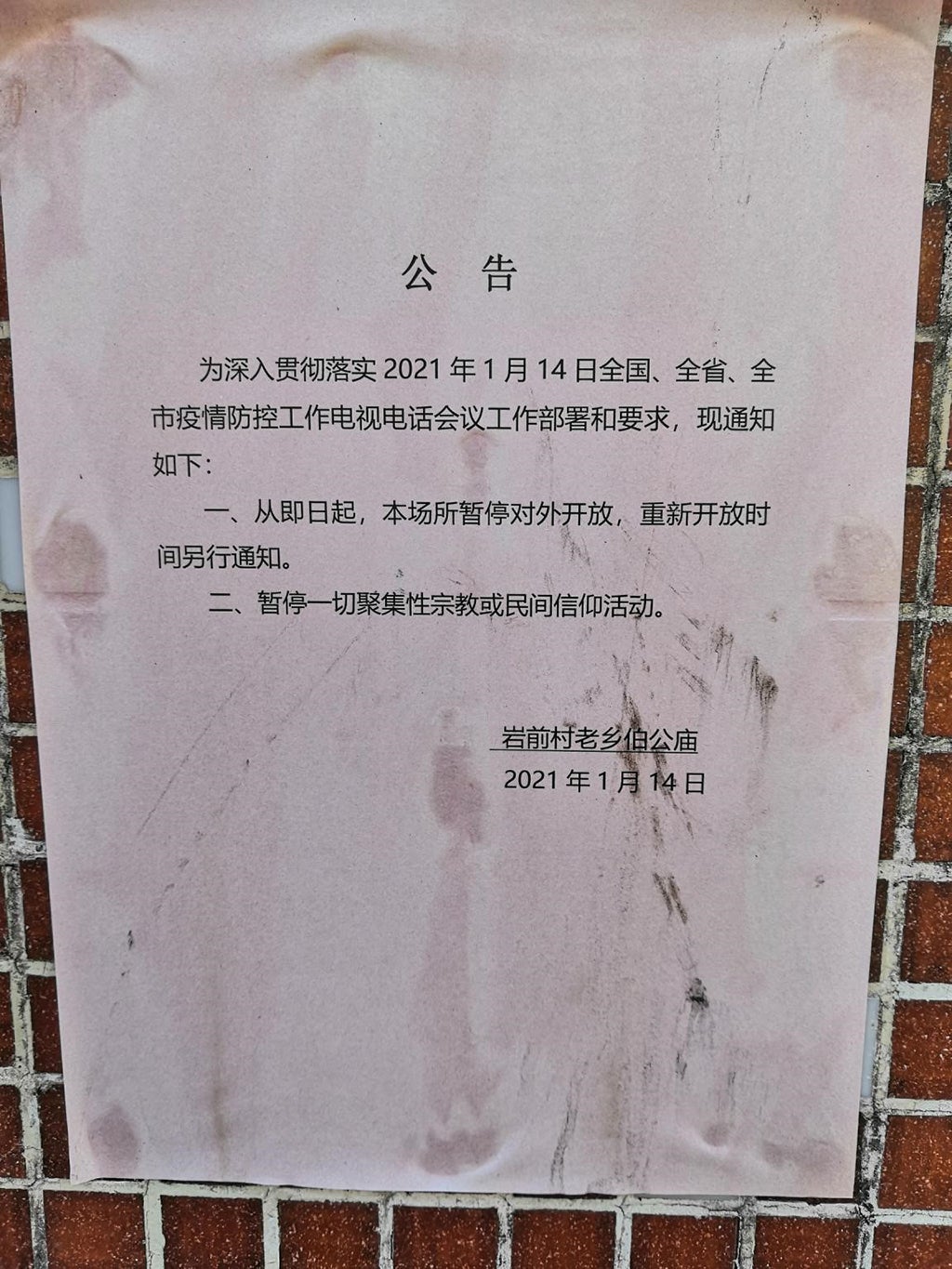

Figure. 2. The Closure Announcement of Earth God (Bogong, 伯公) Temple

The third phase was the 2021 Chinese New Year period. Given the second wave in some northern parts of China, as well as the potential risks expected during the big festive period, the governments in Teochew regions ordered local temples to suspend their activities and close temple doors again (Figure 2). Yet, the state-oriented monitoring measures were mainly only targeted at large-scale temples. Considering the low risk of virus transmission, some local committees opened up their small- and medium-size temples at midnight on Chinese New Year’s Eve as well as during the Lantern Festival. Especially for those temples without doors and merely wrapped with big plastic sheets that doubled up as ‘walls’ (Figure 3), local residents could still sneak into the internal space and carry out ritual practices therein.

Figure. 3. God of Heaven (Tiangong, 天公) Temple covered with a big plastic sheet

From the above, it is evident that the operation of village temples in Teochew regions evolves along with the shifting state regulations during the pandemic. It also suggests that the extent to which local temples are open for communal rites is simultaneously contingent on local temple committees’ decisions. Different degrees of lockdown measures as well as changing temple operations have consequently prompted local Teochew people to find alternative ways to continue practicing customary ritual activities, for which we would invite you to read our commentary paper titled as “Religion in times of crisis: Innovative lay responses and temporal-spatial reconfigurations of temple rituals in COVID-19 China” accepted by the journal Cultural Geographies to discover more.

Disclaimer: The views and opinions expressed in this article are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the position of the blog editorial team or the Asia Research Institute.

South Asia | Southeast Asia | East Asia | Other Places | Hinduism | Buddhism | Islam | Christianity | Other Religions

Dr Chen Ningning is a research fellow at the Religion and Globalisation Cluster, Asia Research Institute (ARI), National University of Singapore (NUS). She obtained her PhD from the Department of Geography, NUS. Her research interests include the fields of religion and sacred space, rurality and rural transformation, Chinese lineage culture and Chinese diaspora. At ARI, she is (co-)working on two projects: one is on Chinese clan associations (Huiguan) and their transnational networks between China and Southeast Asia, and the other is on transformations of Asian religions in a pandemic.