Forest People Confronted by COVID-19: Representations, Rituals and Practices of Pala’wan Highlanders

contributed by Nicole Revel, 21 May 2021

Cover Image: Amrang, a hamlet in the highlands. Picture credited to the author, 1981

The Pala’wan Highlanders form a small egalitarian forest society living in the island bearing the same name in the Philippine archipelago. The habitat of these hunters equipped with blowpipes, gatherers and shifting agriculturists is scattered, forming small hamlets separated by valleys around Mount Mantalingahan.

According to their animist ontology, si Pangkät is a “Malevolent”, Taw Märaqat, the carrier of all “illnesses”, ingläw or balaq. Pronouncing his name is avoided in order not to hurt him. Highlanders demonstrate respectful behavior by referring to him as Upuq Ingläw, “Grandfather Illness”. He is assimilated to Säqitan (“Evil Doer”), doubtless the most dreaded of all (Revel 1990).

Pangkät is the cause of “serious infectious and contagious diseases,” dätdakit näng kälanq sakit, that provoke an epidemic, or läwläbäw. A läwläbäw entails a human community in a given location – in this case the foothills and the highlands in the southern part of the island – at a specific time – during the Northeast monsoon - threatened with death by an incurable disease.

What is Läwläbäw?

Läwläbäw is indeed “an epidemic”, but of a special kind. One serious outbreak recorded as läläbäw in history is the measles epidemic of February 1972 located between the Tämlang and Mäkägwaq Rivers valleys. According to the Pala’wan, its “signs” pägindanan, are: “chills and cold,” ramig and sipun, “access to heat and cold,” agnäw, “fever”, “inflammation of the entire body,” mämuräd bilug, “chest pains,” mapyät däbdäb, “short breath,” and “panting,” kurang ät ginawa. Abay, or respiratory complications, manifest as a very painful sensation of a sharp and burning object, taräm, piercing the chest. Victims suffer various symptoms ranging from “red eyes”, or mata märägan, burning sensation (conjunctivitis); “chest constriction” ,mäpyät däbdäb; exhibits“panting”, kurang ät ginawa. They also “cough”, ikäd, which becomes ikäd-ikäd, designating “pulmonary complications” (bronchitis, pneumonia, broncho-pneumonia). In line with the symptoms listed by the Pala’wan, use of the term läwläbäw is hence reserved for epidemic respiratory system diseases and as such, the COVID-19 outbreak qualifies as one.

In the Highlands, people are totally deprived of healthcare assistance. People are very fearful of läwläbäw - sicknesses that strike the respiratory system and can be fatal without due treatment. According to their typology of illness, the Pala’wan have recourse to diverse protective “charms”, sukang, strings of leaves “to repel” ailments, pänulak, and “magic formulas”, tägtag. For läwläbäw, they resort to an annual ritual well known amongst the Tagbanuwa, farther in the North, and the Tausug in the Sulu archipelago farther in the south, as well as in Borneo and Indonesia.

The collective ritual of Tuläk bäläq,“Driving away disease”

Every year when the “Monsoon of the Coconut”, Barat ät Nyug (Scorpio constellation in November) comes, and the late varieties of rice are being harvested, the period of Täbäs, “the End”, begins. It marks the end of an annual agrarian cycle.

Then, the Pala’wan see tugbuq (Saccharum spontaneum) blooming in the river beds. This grass, according to their representations, is the rice of Pangkät, “The Evildoer,” the staple food that requires an assortment just as in any meals for a “genuine Human”, Täw banar. The “soul-double”, käruduwa, of a person is a complementary dish, part of the assortment, isdaqan, that Grandfather Diseases wants to eat. It is hence the season that precedes and foreshadows the spread of epidemics affecting the respiratory system.

According to custom, in order to ward off the dangers ahead, “the Headman”, Pänglimaq, must prepare offerings in the presence of members of the local group for their protection. He must build a mäligay, a small shelter on a raft, with a roof decorated with four pleated brooms, and prepare delicate offerings (consisting of 7 bowls of sticky rice, 7 plates of fried chicken or 7 live chicks, 7 sugar canes, 7 cigarettes, 7 betel quids and glasses of water) to deposit in the shelter. They are meant to drive away respiratory epidemics.

On the beach, these offerings are placed on a small raft and accompanied to the sea where it is hoped they will drift at the whim of waves and winds to the open sea. A few years ago, on my way to a neighboring island with my outrigger boat, I chanced upon a small raft loaded with offerings floating in the open on the West Philippine Sea - an auspicious sign of a deadly threat perhaps sent away.

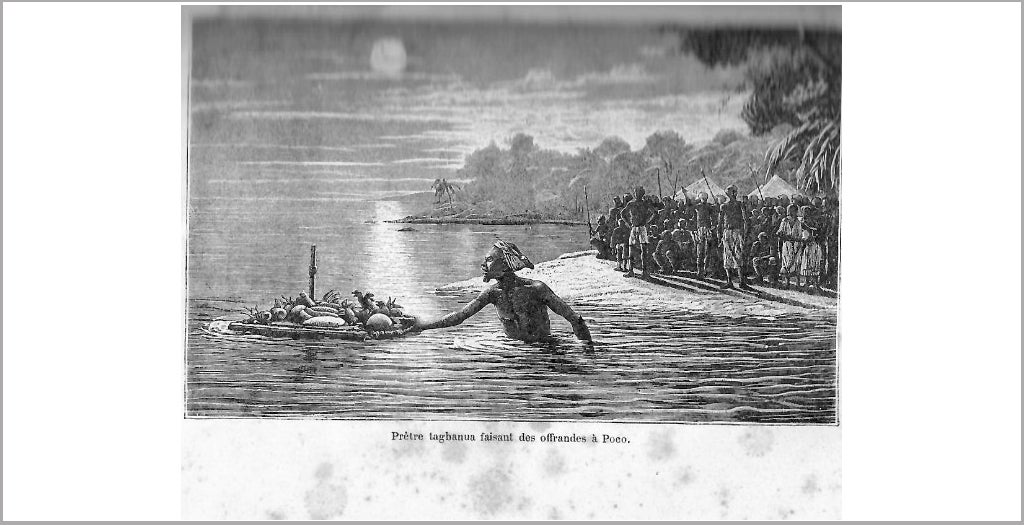

Figure 1. Alfred Marche, 1887, Six années de Voyages aux Philippines, Librairie Hachette, Paris, 406p. chap XV: Les Tagbanuas - Moeurs et Coutumes, pp. 319-333

The Tagbanuwa have a hierarchical society and a cosmogony quite different from the Pala’wan. In order to guard the human community from the terrifying Salakap - dangerous spirits that bring forth epidemics floating on sakayan (large canoes transporting the souls of the dead to “the outer limits of the world”) - the Tagbanuwa used to follow two rituals. Pagbuuyq is performed three times a year, whereas the other, Runsay, of greater importance, is celebrated only once a year, four days after the full moon of December.

The ritual Runsay consists of five phases that is carried out in the presence of the entire Tagbanuwa community and for the common good of all its members (Fox 1982). In the last phase, as soon as the ceremonial raft disappears in the darkness of the high seas, men and women on the shore rejoice and begin to sing and dance until dawn. By way of these elaborate rituals, they attempt to thwart the plan of the dangerous spirits, Salakap. Floating a raft loaded with delicious food (chicken, fish, cooked rice, betel quids) is an act of appeasement and seduction to ward off misfortune.

“Announcement of a contagious disease”: Päsawud ät ingläw

The COVID-19 pandemic has emphasized the need for all of us to take responsibility for how our actions can affect society. Similarly, the Pala’wan Highlanders, who live between 100 and 900 meters in altitude in scattered habitat surrounded by the huge forest of dammars and dipterocarps, have developed their own response to epidemics. They practice isolation very strictly, avoiding all contact by instituting aliq (quarantine). They withdraw to the Highlands, living in an autarchic state, and prohibit all access to hamlets and houses.

In our day, they have radios and mobile phones; they are therefore warned by the airwaves, but observe complete silence. If someone calls them, they do not answer. On the borders of Tigaplan River, around Mount Ilu-ilu, from March 16th to mid-May 2020, they did not come down to deposit the “resin” crystals, bägtik, that they harvested in the forest of Käbätangan “the Trunks” in the warehouse of Ämas. As a result, they did not receive remuneration, nor did they try to pick up the gantang of rice (1 gantang = 8chupas = 2.5kgs.), canned food and other products from the National Government, Social Amelioration Program (SAP) through the Department of Labor and Employment, the Municipality of Brooke’s Point and other NGOs. It speaks eloquently of their capacity to live in relative self-sufficiency, relying on the products of their upland fields, uma – a complex ecosystem and subsistence garden – and of the houses’ surroundings, lagwas, a vegetal clutter like the nearby forest, rich in semi-protected useful plants (fruits, tomatoes, garlic, medicinal and technological plants). They also rely on the “forest”, gäbaq, and nearby secondary forests.

If someone tries to go to their homes, everyone runs away and hides in the forest. The hamlet is deserted and the people only reappear after the intruder leaves. This solidarity among the Pala’wan reveals the inviolability of the social norm of strict isolation, their one and only recourse in confronting läwlabäw.

In September-October 2020, the Highlanders maintained their own quarantine, avoiding the little “markets,” tabuqan, in the foothills as well as the town of Brooke’s Point. Until November, they were harvesting the successive varieties of their upland rice and remained self-sufficient. According to my personal communication with Norlita Colili, the area coordinator for Palawan of Non Timber Forest Products Exchange Program (NTFP-EP), Philippines, only a few men brought down their collected “resin”, bägtik, to the warehouse of Ämas.

Until the 1970s, they used a pre-Islamic syllabary of Indian origin which they had borrowed at the turn of the 20th century from their Tagbanuwa neighbors called "Surat Inabärlan or Surat Tagbanwa" (Revel 2007). This syllabary did not function as a conduit for knowledge or for composing ambahan poems like those composed by Hanunóo young men during the age of romance in Mindoro. Instead, they had a completely different function: to send letters, notices and announcements to establish long-distance communication between kin and affiliates, in order to maintain social rights and duties in an endogamous region. It was a question of transmitting commands, imperatives, and even authoritative words. Examples include Tingkag, “Convocation”, Bawal “Prohibition,” Tabang “Call for help,” Ukuman, “Judgment,” as well as a major warning: Päsawud ät Ingläw, “Epidemic Announcement”.

Figure 2. Pala’wan message engraved on bamboo at crossroads to deter visitors. Photos, transcription, translation credited to author and montage to Hermine Xauflair

Writing functions as a kind of loudhailer, exercised not within a religious or literary idiom, but of a public health and juridical idiom, invoked by the Pänglimaq, “the Headman” or Ukum, “the Judge”. These were very brief missives, doomed to disappear by the ephemeral nature of the material on which they were incised (strips of bamboo, banana leaves). They were effective, however, in protecting local populations. To this end, the Pala’wan erected fragile signs at crossroads (Figure 2), bearing concise messages to stop any visitor. These signs forbade visitors, simply but formally, from visiting pala’wan households and their inhabitants.

Figure 3. A closer look at the incised pole

The situation today

By June 21, 2020, the Philippines (population 110 million) had declared 30,052 COVID-19 cases, with 7,893 recoveries and 1,169 deaths. For urban people in Metro Manila, this pandemic is accompanied by a tremendous loss of work and jobs, increased violence, and intense misery in urban slums. These numbers do not seem very high considering the urban population of Metro Manila and Cebu. However, the very insularity of this country (7,641 islands) is an obstacle to the propagation of the epidemic. Palawan has thus far been spared from infection.

As of today, after implementing one of the longest lockdowns in various islands and large cities, the situation has worsened and the coronavirus is reaching the south of the main island. Despite these measures, according to the WHO statistics released on October 17th 2020, the Philippines had the highest number of COVID-19 cases in Southeast Asia, and the virus continues to spread.

Since early 2021, several vaccines have become available and the government has started to implement vaccination campaigns following the criteria of class age to reach a dense but dispersed population across a very fragmented insular country. In spite of these campaigns, the virus and its variants continue to circulate more and more through the archipelago. It has recently reached the little town of Brooke’s Point, in southern Palawan - with 4 cases reported. In response, the Government has chosen to confine the people in the lowlands once again.

In the Highlands, men and women persist in following their traditional ways as they have the capacity to survive in autarky thanks to the tubers in their upland fields and the forest products they know how to gather. This is not the time for collective rituals as they are in the middle of dry season and scarcity. Rice and maize are slowly growing and Monsoon Rains will burst only in June.

References

Revel, Nicole. (1990). Fleurs de paroles, Histoire Naturelle Palawan, 3 vol., Peeters /SELAF, Coll. Ethnosciences 314, vol I. Les Dons de Nägsalad, 385 p.; Coll. Ethnosciences 317,vol II, La Maîtrise d’un Savoir et l’Art d’une Relation, 322p. Ch. 3 La Nourriture des Invisibles ou ‘l’ Homme pris’, pp. 79-124.

Revel, Nicole. (2017). Les Arts de la Parole des Montagnards Pala’wan. Une Mémoire vivante en Asie du Sud-Est / Pala’wan Verbal Arts. A Living Memory in South-East Asia, Geuthner, a multimédia trilingual book (Pal/Fr/Engl), 316p.,+10 DVD Roms (compressed in 5). Cf. Booklet VII, Surat : the letter, the script, the message pp.188- 200.

Fox, Robert Bradford. (1982). Religion and Society of the Tagbanuwa of Palawan island, Philippines Monograph N°9 National Museum, Manila, pp. 238-246.

Disclaimer: The views and opinions expressed in this article are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the position of the blog editorial team or the Asia Research Institute.

South Asia | Southeast Asia | East Asia | Other Places | Hinduism | Buddhism | Islam | Christianity | Other Religions

Nicole Revel, emeritus senior researcher at the CNRS, Paris, and Dr Honoris Causa (Humanities) at Ateneo de Manila University (2009), dedicates her life research to the safeguarding of endangered languages and cultures of the Philippines. As a linguist-anthropologist, her monographic work focuses on Palawan language (1978), lexicography, semantics, pragmatics, rhetoric and poetics. ‘Fleurs de paroles. Histoire naturelle palawan’ (3 vol.,1990-91) is her major work in Ethnoscience. ‘Pala’wan Highlanders Verbal Arts’ (2017) is her latest multimedia publication. From 1991 to 2001, she coordinated an international Seminar on ‘Epics’ in a Program of the Decade for Cultural Development (Unesco) : the ‘Integral Study of Silk Roads: Roads of Dialogue’. Following the digital revolution, she set in motion her vision of a multimedia archive for long sung narratives: the ‘Philippines Epics and Ballads Archive’. Since 2011, this collection (34 vol. 5 hard disks), has been deposited at the Rizal Library, Ateneo de Manila University and is accessible free of charge here after registration: Http://epics.ateneo.edu/epics.