Touchless Technology, Untouchability, and the COVID-19 Pandemic

contributed by Ankana Das, 25 May 2021

The everyday life of humans has been severely affected by the outbreak of the COVID-19 pandemic. As India grappled to establish measures to combat the spread of the virus, the centrality of socio- cultural and religious traditions in the country took the shape of special religious adaptations that function as measures for disease prevention. India imposed a nationwide lockdown on 24 March 2020, which caused radical changes in citizen’s everyday lives, particularly in the realm of religious praxis. The Indian government handled the pandemic in a manner that is congruent with Hindu religious sentiments. Early into the lockdown, on March 22, Prime Minister Modi urged citizens to create noise by banging utensils; this was supposed to simulate a cacophony of sounds usually associated with temple spaces. One week later, on April 5, people also lit diyas in their homes at his urging. Alongside these, newspapers’ reportage and social media revealed a rising trend in viral videos of people from different parts of the country seeking divine intervention to end the “curse” of COVID- 19.

Fig. 1. (left) Man worshipping Corona idol. (Source: The Hindu) and Fig. 2. (right) Women engaged in appeasing Corona Devi. (Source: India TV)

People from different states, such as Bengal, Assam, Bihar, and Orissa, etc. took to appeasing a newfound goddess known in different parts as Corona Mai (Mother Corona), or Corona Devi (Corona Goddess) who they worshipped like any other Hindu god. The coronavirus for them is an act of God; a reminder that humans are not always in control of their environments and are always meant to be dependent on God. Similarly, there were also others who used the virus to amplify Hindu theories on impurity, infection, and degradation. They saw the coronavirus outbreak as a reminder of the importance of untouchability. Practices such as physical and social distancing, frequent sanitization of spaces and bodies became sites for cultivating beliefs and notions about caste, and more specifically about untouchability.

The Hindu temple spaces in the COVID- 19 pandemic

In a typical Shiv temple in South Delhi, 17-year-old Shivam (name changed) assists his father in his daily temple rituals. He is a devout shiv bhakt (devotee) and says with confidence that his comprehension of the gods’ vocabulary as well as his understanding of religious scriptures is more informed than many people who might be vocal on social media. For Shivam and his family, who reside in the temple compound, the pandemic has been an exceptionally difficult time - without the presence of devotees, the temple’s space felt alien to them.

From August 2020, the government imposed certain necessary precautions and started allowing devotees to visit religious sites. Devotees however, must maintain physical distancing and abide by government rules by wearing face masks and frequently sanitizing their hands. Temple gates also sold sanitizer bottles along with bottled Ganga Jal, and other religious items such as sacred amulets, etc. The faith in religious symbols for good health and safety (as with sacred amulets) is thus marred with the championing of science and modernity (sanitizers, etc) for the sake of survival. For Shivam though, the use of sanitizers was permissible, but only if people also recognize the efficiency of the other sacred forms of purification, such as the Ganga Jal.

The “natural” Ganga Jal as sanitizer? The science behind and its Caste angle

Fig.3. Bottled Gangajal advertised online. (Source: Gangajal)

The water from the river Ganga has long been considered pure and sacred. However, claims to the purity of the river water have come under serious attack recently (though still pre- COVID- 19 times). Although many Hindus continue to consider the Ganga as a source of unquestioned purity and sacredness; during the pandemic, several claims popped up regarding the efficiency of Ganga Jal as a treatment for the deadly virus. Couching their argument within the language of science, believers insisted that since Ganga Jal never rots, it can be used as a natural sanitizer. Some devotees even claimed that Ganga Jal is more efficacious than science- based medicine.

However, there are many Hindus who also questioned the purity of the Ganga Jal in contemporary times. As a high schooler with a keen interest in science and technological inventions, Shivam respects the discipline and enjoys opportunities to explain divine interventions through scientific methodologies. While talking about the efficacy of Ganga Jal as a natural sanitizer, he said, “Nah, it might not work as accurately as a alcohol- based sanitizer. Do you even know what amount of pollutants go into the Ganga?” He then earnestly cited statistics on the number of industries that empty their waste waters into the Ganga, thereby reducing the potency of the revered sacredness of the water.

But I asked sarcastically, “Is the Ganga not divine? How can one reduce its divinity by mere mortal acts of polluting it by industrial wastes?” To this, his father, the aged priest Prabhakar said, “Of course it is divine. But these days the number of non- believers have outnumbered believers, therefore creating a disbalance in the harmony between nature and modernity.” His idea of the natural coincides with that of the divine, which is interesting because his son has been trying to harmonize religious and scientific precepts. Prabhakar further continued, “When non- believers get together and disrespect religion, be it by bypassing caste laws or religious deliverance, believers stand at a risk of losing out the relevance of the divine.” Prabhakar also believes that the current virus outbreak is an indication of divine displeasure caused by society’s rampant ignorance of traditions and its increasing reliance on science.

Shivam and his father’s engagement with science and religion complicates commonplace assumptions about intersections between the scientific and the religious. Their emphasis on performance and everyday practice both goes against and along the grains of doctrines, texts and beliefs that contemporary engagement with science and technology is presently occupied with. On one hand, Shivam and his father conflate the natural with the holy, but on the other, they also accept scientific postulates on the natural world. Ironically, they also evince a steady denial of science from a religious standpoint.

Science, technology, and the question of Caste

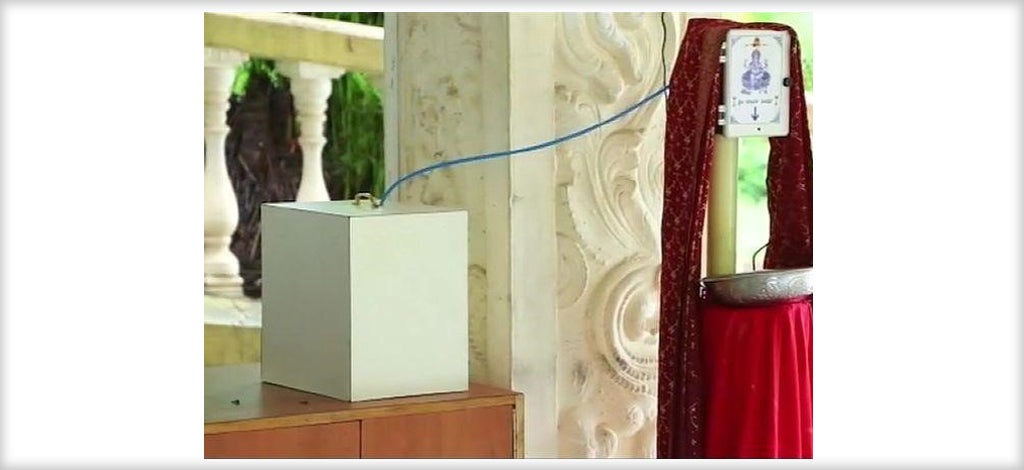

Fig. 4. The Touchless Holy water dispenser. (Source: TimesNowNews)

A Hindu temple in Mangalore was lauded on social media for its installation of an automatic “holy water dispenser” to help reduce the risk of transmitting germs. It distributes individual doses of water without devotees having to touch any part of the device. The machine, says its developer, is contactless so that devotees can maintain hygiene while engaging in religious activities. Though this machine works on a very basic mechanism, its presence inside a temple is what has attracted people the most.

Fig. 5. Man ringing the touchless temple bell. (Source: Catchnews)

In another instance, in a temple in South India, devotees can now ring the holy bell without actually making any contact with the bell. This “contactless bell” is developed in a way so that it can be rung without physically touching it. When religious institutions reopened around June, this particular temple became a popular destination for religious as well as non- religious people to witness what they called the “automatic- bell.” The sensor in the bell allows it to be rung every time a person comes beneath it with folded hands.

Both these technologies use electronic sensors to translate the actions of humans towards the divine and help reveal the present- day religious consciousness of humans, especially in a post- COVID scenario. It helps theorise basic tenets of modern- day religiosity. But it also complicates questions like: when the idea of the divine is embedded with a dependence on the electronic, how can we fit in established codes of caste in Hinduism? Or, how can the “touchless temple bell” or the “automatic holy- water dispenser” help conceptualise untouchability in modern societies where urbane casteism is rampant?

Here, with the help of technology, casteism is reimagined on the lines of a logical and rational conception. It reinforces existing social barriers and prejudices against lower castes and Dalits by regulating the concept of touch and further, that of contamination. It validates and facilitates untouchability by making the practice of physical contact mechanical, thereby less stigmatizing on humanistic grounds. One might argue that these technologies lift prevalent ideas of physical touch by making touchless-ness universal for all devotees in the temple space. But we have earlier seen how the spread of COVID- 19 has been accursed on non- believers in the caste system, as was the case with the priest from Delhi who believed that if all persons maintained caste laws of purity and pollution, the virus would not have spread the way it had in present day. Therefore, to hope for a better world for Dalits in a technologically powered landscape also seems improbable. It is only likely that the comfort of these technologies might be furthered in other spaces of social contact so as to systematically enforce untouchability.

The costs of touchless technologies

One might argue that touchless technology instead of furthering caste sentiments, might aid in its dismantling. That is, if the aspect of “touch” is done away with, then perhaps notions of caste will also be less manifest in everyday rituals. But in reality, the idea of caste is not simply limited to that of the physical aspects of untouchability. It is entrenched in everyday values and other social perceptions about merit, capability, authority, etc. To assume that touchless technologies will assist in dispelling caste prejudice is a very simplistic way of looking at the problem. Even outside the discourse on caste, if instances of touchless technologies induced by the COVID- 19 pandemic expand into other sectors of public life, then we would need to rethink how we envision human touch/ contact. While technology- imbued temple paraphernalia is appreciated, we also need to be wary of discrimination that can accompany the ideas that they inculcate.

What appears to be dystopian assumptions about the connections between these technological inventions and untouchability might not be only speculations. The Indian government’s Technology Vision 2035 from the Department of Science and Technology outlines a technology driven future where the notion of “human touch” in several public and commercial sectors is discouraged. Also, from fictitious imaginations, a recent commercial TV series, titled Leila amply explores what a technology- assisted future might look like. Its portrayal of technology- assisted human segregation, perpetuated by an anarchist government that syncs with popular majoritarian Hindu sentiments, resembles present day happenings around the country. Amidst all these, what we are left with is hope, and our scholarly weapons of engaging with the problems and encountering it academically.

Disclaimer: The views and opinions expressed in this article are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the position of the blog editorial team or the Asia Research Institute.

South Asia | Southeast Asia | East Asia | Other Places | Hinduism | Buddhism | Islam | Christianity | Other Religions

Ankana Das is currently a PhD student at the Department of Humanities and Social Sciences at the Indian Institute of Technology, New Delhi, India. She works on religious consciousness, transformation, and transgressions, looking at how caste, class, and political influence permeate through layers of religious meaning making. She can be reached at ankana.das@iitd.ac.in