The Cult of Goddess Pattini at a time of Pandemic: Gammaduwa as a Strategy of Supernatural Protection

contributed by Premakumara de Silva, 3 June 2021

Cover Image: Marble statue of Goddess Pattini at her main shrine, Navagamuwa near Colombo. Photo credit: Pradeep Dambarge, 26 July, 2016

‘The goddess descends from the wind and cloud and sky

She looks at the sorrows of Sri Lanka with her divine eyes...

With compassion and kindness protect us mortals

O Seven Goddess Pattini come into your flower throne.’

(Excerpt from the Pahan Pujava to Goddess Pattini, quoted in Obeyesekere 1984: 82 cf. de Alwis 2018: 51)

During times of uncertainty and danger, people often use rituals to reduce their stress and exert control over their environment. A global pandemic is also a time of significant transition and uncertainty when people have greater need for physical and social support. Over the past year, people have used their ritual traditions as a strategy of invoking supernatural power to control the spread of COVID-19 in their communities, and Sri Lanka is no exception in this regard. The outbreak of the COVID-19 pandemic in Sri Lanka saw masses seeking ritual blessings as they took the initiative to conduct special religious rituals such as the three-week-long continuous Pirith chanting or Buddhist prayers, Bodhi pooja, as well as performing traditional deity rituals like Kohomba Kankariya and Gammaduwa. Alongside these rituals we saw the rise of traditional Ayurvedic medicine ‘miracle cures’ promoted as means to combat the growing threat of the deadly coronavirus. Such ritual blessings were invoked on infected patients, frontline healthcare staffers, all of Sri Lanka and even all of the world in hopes to alleviate the situation, amidst the parallel pandemic of fear and stigmatization resulting in a number of social problems and related public health crises (Silva 2020: 27)

Chanting, Blessing and Performances

In the Buddhist world, the use of Suthra (pirith) chanting as a forceful protective measure used to eliminate evil spirits and to protect the society from evil influences and pestilences has a long history. During this pandemic, Sri Lankan Buddhist monks started pirith chanting a type of prayer to combat against COVID-19 at temples island wide on a weekly basis. The chanting of the Rathana sutra as a form of ‘sonic protection’ was discussed by Gajaweera and Mahadew in relation to the politics of securitization. Apart from invoking the sonic power of Buddhist suthra chanting in Sri Lanka, there is a system of belief for invoking ritual protection containing the spread of infectious diseases that locals refer to as deiyange leda, or “diseases of the gods.” Like COVID-19, most are viral diseases: chickenpox, measles, mumps and smallpox. In general, they are also referred to as deviyanne dosa (dosa caused by gods): under this classification are subtypes of dosa, all caused by the wrath of the gods (deviyo) of the Sinhala Buddhist pantheon. Among those gods Vishnu, Saman, Kataragama, Pattini, Kali and Suniyam are the most popular gods in contemporary Sri Lanka. The first four gods are regarded as the guardians of Sri Lanka and are considered more benevolent figures compared with the more punitive Kali and Suniyam. Rituals such as Gammaduwa are performed to honor these deities and seek blessings to overcome dosa caused by them, particularly the goddess Pattini (cover image). Such traditional rituals, called Shanthi Karma, or rituals of solace, are a combination of dance, chanting, drumming and making offerings to encourage blessings from the deities to eliminate evil spirits. There are many such rituals in Sri Lanka, some of them are regionally specific, but overall each is performed with the similar purpose of warding off diseases (see Obeyesekere 1985; Kapferer 1983, Scott 1994, de Silva 2000, Bastin 2002, Reed 2010).

Figure 1. Pattini at her shrine near Colombo. Photograph by Premakumara de Silva

The cult of Pattini as a medical system

This essay draws extensively from the comprehensive and detailed study of the worship of Pattini in Sri Lanka and South India by anthropologist Gananath Obeyesekere –The Cult of the Goddess Pattini (1984). According to him, Pattini worship is male oriented, as is all Buddhist worship, albeit for very different reasons. Her priests or kapuralas were trained personnel at one time, but this is changing, as is the perception of Pattini. The cult is at once a propitiatory system and a medical system. The metonymical extension of congregational participation to congregational patienthood is enacted in the collected posture for relief from all trouble (dosa) and affliction. The congregational patienthood is ensured not only of a pragmatic curative nature of the community concern, but also of an expressive and emotional nature of congregation as well. The three elements of the ayurvedic medical system (vata/air/breath; pitta/fire/bile; sema/water/phlegm) indicate the upset of human homeostasis, which is believed to be caused by physical influences or the agency of spirits, both of which are caused by planetary misalignment and karma (de Silva 2000).

One of the goals of the gammaduwa is to cure, control, protect against, and exorcise the negative effects of the dosas. Thus, for example, ritual fire trampling controls an excess of fire (pitta), and ritual cutting of water controls an excess of water (sema/phlegm). Pattini is also known for the sacred anklet (salamba) she wears, an amulet said to have special curative powers that can rid people of conditions such as smallpox, chickenpox, whooping cough, measles, and mumps. She is a guardian deity who protects people from diseases and calamities, and interacts favorably with nature, bringing rains, promoting fertility and the growth of vegetation. Essentially, Pattini represents maternity, purity, healing, and piety embodied in a divine feminine form.

One of the crucial assertions of Obeyesekere’s argument in the book relates to the decline of Pattini's cult. "The very popularity of a deity as a god granting favors will, in the long run, render him (her) otiose" (1984: 66). According to him, the logic is that the more benevolent and compassionate the god, the less involved he/she becomes in the affairs of the world which subsequently makes him/her progressively ineffective. Furthermore, benevolent gods tend to be idealized, so that one does not typically ask them for favors for mundane matters. As a result, the god becomes progressively more “remote” (1984: 65). Pattini is a more benevolent female god now aspiring to be a bodhisattva (perum puranava) and able to attain Enlightenment or Buddhahood. Hence, her position has been taken over by her servant, the ferocious Hindu demoness, Kali (see Bastin 2002).

However, since Obeyesekere conducted his research between the 1950s and 1970s, Sri Lanka has undergone drastic changes which has affected the veneration practices of the devotees of Pattini and her Tamil variant Kannaki. Most significantly, Obeyesekere’s research ended before the beginning of the civil war that erupted in Sri Lanka for over three decades, from the 1980s to 2009, and not to mention the post-war situation including this year of the pandemic. As I argue elsewhere the importance of deity worship, including Pattini, has not been declining, but rather such forms of worship are being rearranged by adjusting into modern circumstances (de Silva 2000).

While Obeyesekere develops a major historical thesis arguing that the Pattini cult had its origin among heterodox southern Indian Buddhist and Jain merchants, she is not foreign to Hindus as Tamil Hindus also know her as Kannaki and Sinhala Buddhists know her as Pattini. Rather than disappearing, the persistence of devotion to Kannaki-Pattini is an inspiring example of Hindu-Buddhist syncretism in Sri Lanka (de Alwis 2018).

Regarded as the goddess of fertility and health, Pattini is the only female deity who is accorded a place of honour within the Sinhala Buddhist pantheon. She is considered to be one of the four guardian deities of Sri Lanka (hatara varam deviyo) and is represented in the annual Asela procession of the Temple of Tooth Relic in Kandy. There are many large and small shrines dedicated to her throughout the country, although the worship of the goddess Pattini is most popular in the coastal regions of the Western and Southern provinces and in the province of Sabaragamuwa which lies in the interior of Sri Lanka adjacent to these two provinces. The central shrine of Pattini is in Navagamuwa - 37 km away from the east of the city of Colombo. The gammaduwa is a key ritual performed at Nawagamuwa during the annual festivities of the shrine.

Gammaduwa as a ritual protection

The gammaduwa, also known as Devol madu shanthikarmaya, is a ritual tradition that invokes the blessings of the goddess Pattini. Gammaduwa means "a hall in the village", constructed to worship gods by the people of one or more villages. Traditionally, it is practiced predominantly in the low country, performed by a kapurala (priest, spiritual leader and healer) to ensure the well-being of the village and a plentiful harvest. The gammaduwa comprises offering plants (betel leaves and festival boughs) and lights, planting the torch of time, performing fire trampling rituals and ceremonial dances for the participating gods. Through these acts, Pattini's status as mother goddess is reaffirmed.

Figure 2. Gammaduwa performance at Colombo metropolitan city, Maharagama. Photograph by Premakumara de Silva

But today gammaduwa is performed for many reasons. For example, during the civil war it was performed to protect the country (rata), nation (jathiya) and the arm forces from the LTTE, a separatist group and those who were against the Sri Lankan state (outside forces). In other words, gammaduwa has transformed from protecting village communities into invoking Pattini’s protection to the whole nation, precisely to Sinhala Buddhists, thereby fostering Sinhala Buddhist nationalism. During such nationalist reformulation of the cult, the syncretic nature of Kannaki-Pattini has been erased.

The most recent change can be observed after the outbreak of COVID-19 in the country. Though the government did not allow communal gathering during the first outbreak of the pandemic, this decision was gradually relaxed after managing the second wave. According to media reports, there were several gammaduwas organized by different groups such as local level government officials, political authority, and media channels to seek the protection of Pattini to prevent the spread of the coronavirus in the country. One such gammaduwa was held on 6th February 2021, in Gampha District in the western Province, where the origination of the second wave had taken place in a garment factory’s premises (figure 3).

Figure 3. The Gampha (Diwlapitiya) gammaduwa under COVID-19 circumstances. Photograph credit to Lankadeepa, 7 February, 2021

A popular private TV channel, Hiru TV, also organized a fairly modified and elaborated gammaduwa known as ‘sath paththini seth shanthiya’ (blessing of seven virgin mothers/pattinis such as seven manifestations ('avatars'), known as Orumala, Karamala, Gini, Devol, Saman, Ayragana and Siddha) at the dawn of the Sinhala-Tamil new year 2021 to protect the country from the coronavirus and to invoke blessings to bring prosperity and happiness to the people of the country. This event was given wide publicity over a live telecast during an overnight broadcast on TV and a panel discussion was conducted to convince the public of the importance of organizing such an event during the pandemic.

<iframe width="560" height="315" src="https://www.youtube.com/embed/uWutI3UCocI" title="YouTube video player" frameborder="0" allow="accelerometer; autoplay; clipboard-write; encrypted-media; gyroscope; picture-in-picture" allowfullscreen></iframe>

Video: Sath paththini seth shanthiya, gammaduwa performance, 13-14 April, 2021. Retrieved from Youtube.

Figure 4. Screenshot of a news report on the above gammaduwa. Credit to Premakumara de Silva

Unlike traditional gammaduwa which represents only a particular troupe of priests known as kapuralas (general term employed for priests of deity cults), the troupe (performers) at this event represented three reputed local dancing traditions, namely Raiygam, Bentota and Matara. The mixing of troupes is mostly common in contemporary modified large scale ritual performances. Holding a gammaduwa has become a large-scale, spectacular, illuminated and expensive affair which usually involves large audiences. As opposed to the traditional form, which is confined to the village, gammaduwa now has become common in urban spaces such as playgrounds, school halls, market places, temples and shrines attracting wider publicity via print, electronic and social media (figure 5). Another point I want to make here is that, in this transformation, the protective and healing capacities of the goddess which are enacted in gammaduwa at the village level as a matter of the health of the social/communal body has extended now to heal the nation as a whole. This is not only happening at gammaduwa, but also at other national cultural performances in the country.

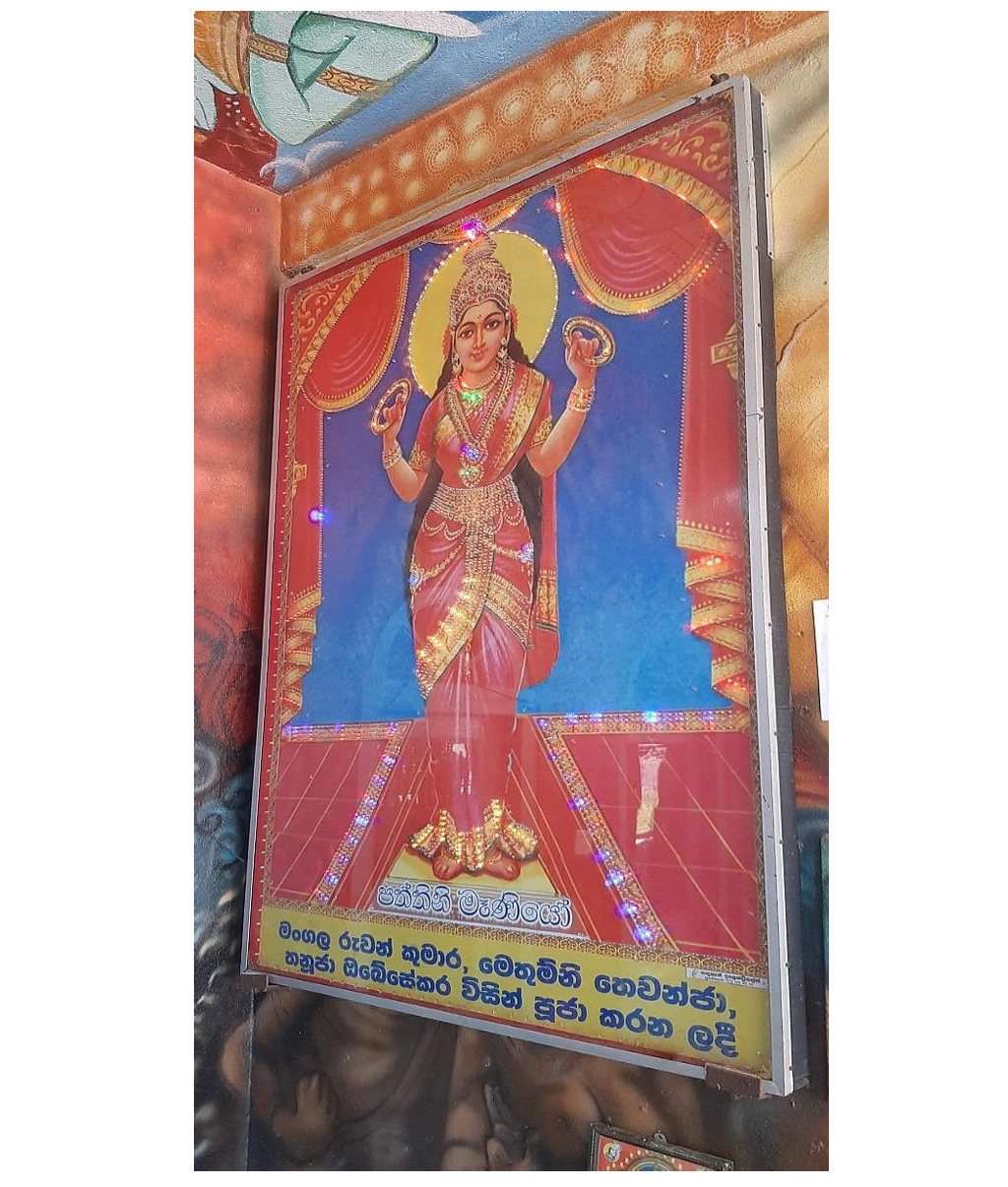

Figure 5. A display banner about gammaduwa for the public. Photograph by Premakumara de Silva

According to my field observations over the last twenty-five years, traditional, village-based rituals like gammaduwa, kohomba kankariya (propitiating as a collectivity of deities in the Kandiyan regions), bali (ritual to address astrologically related misfortunes of planetary deities), and yak tovil (ritual to appease malign spirits like demons) have been used by certain groups to express their ethno-nationalist identities and sentiments in the context of civil war and after. This change indicates that while these rituals used to be village based, they have become larger exorcist and healing rituals which move away from healing a personal/ local social body, to become more about healing and protecting the nation from outside evil forces who try to destabilize the Sri Lankan state and even from new threats like COVID-19.

By considering the transformation taken place in gammaduwa and other local rituals in Sri Lanka, the anthropological understanding of rituals is extended to show how, what is often seen as rigidly structured entities, can become areas for innovation and mutability. While it is impossible to gauge the efficacy of these rituals, they do provide a semblance of hope and a return to “normalcy” to humans that have faith. So even if they have no direct influence over the physical world, rituals provide a sense of protection and control by imposing order on the chaos of everyday life.

Citation

Bastin, Rohan, 2002. The Domain of Constant Excess: Plural Worship at the Munnesvaram Temples in Sri Lanka. Berghahn Books.

De Alwis, Malathi, 2018. ‘The incorporation and transformation of a ‘Hindu’ goddess: the worship of Kannaki-Pattini in Sri Lanka’ In The South Asianist 6(1): 150-180.

De Silva, Premakumara, 2000. Globalization and the Transformation of Planetary Rituals in Southern Sri Lanka. Colombo: International Center for Ethnic Studies.

Kapferer, Bruce 1983. A Celebration of Demons: Exorcism and the Aesthetics of Healing in Sri Lanka. Bloomington: Indiana University Press.

Obeyesekere, Gananath 1984. The Cult of the Goddess Pattini. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Scott, David 1994. Formations of Ritual: Colonial and Anthropological Discourses on the Sinhala Yaktovil. London: University of Minnesota Press.

Silva, Kalinga Tudor 2020. ‘Stigma and Moral Panic about COVID-19 in Sri Lanka’ In Journal of Humanities and Social Sciences Volume 03, Issue 02: 42-71.

Reed, Susan 2010. Dance and the Nation: Performance, Ritual, and Politics in Sri Lanka. Madison: University of Wisconsin.

Disclaimer: The views and opinions expressed in this article are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the position of the blog editorial team or the Asia Research Institute.

South Asia | Southeast Asia | East Asia | Other Places | Hinduism | Buddhism | Islam | Christianity | Other Religions

Premakumara de Silva is an anthropologist/sociologist who currently holds the chair professorship at the Department of Sociology, University of Colombo, Sri Lanka. He has published several books in English and local language, a number of book chapters and over fifty articles on his credit. In 2019, an Honorary Senior Research Fellowship has been awarded by the University of Birmingham, UK. His research interests include political use of religion and ritual, pilgrimage, nationalism, local democracy, youth culture, indigenous study, grass-root development, social welfare, and globalization.

Other Interesting Topics

The Coronavirus Pandemic and the Response of Hoa Hao Buddhists in the Vietnam’s Mekong Delta

The COVID-19 pandemic has affected many people in the Vietnamese Mekong Delta as strict border control measures, especially restrictions placed on the Vietnam-China trade since the second outbreak of the disease in July 2020, have put many agricultural processing factories at risk...

Convergence and Divergence in Health Messages: Spirit-Medium Advice about COVID-19

On September 3rd, 2020, Thjia Chui Mei, the mayor of Singkawang, West Kalimantan announced via a video on her Instagram account that she and her family had tested positive for COVID-19. In a series of videos that followed which were uploaded to YouTube, she documented her time in quarantine...

Javanese Wayang Kulit Responses to the COVID-19 Pandemic

Performances of the Javanese shadow theatre Wayang Kulit have traditionally been imbued with ritual character. Performances have been shown, for example, at important family or local celebrations, or during purification rituals for individuals or entire communities...