How is Chinese Buddhism Coping with the COVID-19 Pandemic?

contributed by Nan Ouyang, 22 May 2020

Chinese Buddhists have been seriously influenced in various ways by the outbreak of coronavirus in China in December 2019. The direct result is the closure of monasteries to the public and the halt of public religious activities.

According to government orders, Buddhist monasteries have been ordered to close their doors since the end of January 2020. Despite the gradual return to normalcy for business since April 2020, it is still uncertain when the religious institutions will be allowed to open their doors to the public again.

The pandemic has meant many Chinese monasteries have been closed for at least four months. Monasteries on Mt. Jiuhua, a famous Buddhist mountain identified as the seat of Dizang Bodhisattva in Qingyang, Anhui, have been closed since Jan. 24, 2020. The local government organs issued an edict for guidance with four points:

- All the religious establishments should be temporarily closed down;

- People should not congregate in the religious institutions, and the time for visitors and sojourners should be shortened;

- Monasteries should have strict rules on food safety, and it is forbidden for monastics to receive food donation from disciples;

- Monasteries should coordinate with related government organs to deal with the prevention of coronavirus, and report in time if anything happens.

Now, in May 2020, with the Chinese government eager to reopen the economy, religious activities considered as low-priority activities are ordered to remain halted.

During the lockdown period, Chinese monastics have responded to the pandemic with their religious knowledge and financial resources in both traditional and innovative ways. On the one hand, Buddhists donate funds, hold dharma services, and donate essential medical resources to overseas monasteries. On the other hand, they use digital methods to preach dharma and interact with followers.

Making donation for disaster relief is the most common method for Chinese monastics to show their support. For instance, Mt. Jiuhua Buddhist Association donated 5 million RMB to Chizhou Charity Federation; the monastery Dizang Flesh-Body Pagoda 地藏肉身塔 alone donated 10 million RMB to Chizhou Charity Federation. Besides, Mt. Putuo Buddhist Association donated 10 million RMB to support the construction of the makeshift Fire God Mountain (Huoshan shan 火神山) Hospital in Wuhan, the initial epicenter of the coronavirus in China.

According to a rough estimation by the author, the total value of donation by Chinese Buddhist communities (including monasteries, foundations, and lay people) reached around 107 million RMB (from Jan. 24 to Mar. 18, 2020) for the victims both in China and abroad.[1] The donation included money, essential medical resources (i.e., faces masks, ventilators, medical gowns), and food (i.e., rice, vegetables).

Holding dharma services is another way to offer comfort for the public and the believers. With the belief in the efficacy of Bhaiṣajyaguru (Medicine Buddha or Healing Buddha) as a divine healer, many Chinese monasteries hosted dharma services to worship the particular buddha and pray for the patients.

For instance, Lingyin Monastery 靈隱寺 in Hangzhou, Zhejiang, held a close-door “Protecting the Nation and Eliminating the Disaster” (Huguo xiaozai fahui) dharma service devoted to Bhaiṣajyaguru from Jan. 25 to Feb. 8, 2020. In order to invite lay people to join the service, Lingyin Monastery registered a QR code on their website, through which those interested could fill in the donors’ names, write down the names of the deceased, and donate money through online payment methods.

Figure 1: The Hall of Medicine Buddha at Lingyin Monastery

Chinese monasteries are also actively making connections with monasteries abroad by donating urgent medical resources, which showcases the international network of Chinese Buddhism. As COVID-19 spread from China to the rest of the world, Chinese monasteries changed their roles from receivers to the donors of medical sources to the monasteries abroad. For example, Fushan Monastery 福善寺 in Fuqing, Fujian, along with Promotion Society of Obaku Zen in Fuqing, donated 70,000 masks to Manfukuji 萬福寺, the center of Obaku Zen 黃檗禪 in Japan on April 2, 2020. Because of Yinyuan longqi 隱元隆琦 (1592–1673), the legendary Chinese founder of Obaku Zen in Japan from Fuqing, these monasteries forged friendly relationships. The donation further strengthened the friendly monastic relationships.

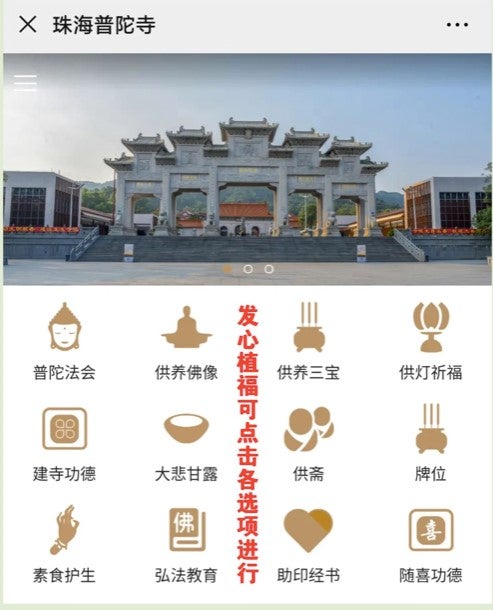

Beyond the traditional forms, some monasteries adopt novel digital methods to promote themselves. Media forms, such as official online websites and WeChat public accounts, become the popular realms to interact with followers. For instance, Putuo Monastery in Zhuhai 珠海普陀寺, Guangdong, has posted a guide to cultivating “online merit fields” (wangluo futian 網絡福田) since the end of March 2020 on its WeChat public account.

By scanning the QR code (Figure 2), one can log into the program, choose from a variety of items (12 categories, see Figure 3) to participate in Buddhist practices at the monastery. The 12 categories include:

- Supporting dharma services

- Making offering to Buddhist statues

- Making offering to the Three Jewels - Lantern offering and praying

- Donating for monastic buildings

- Donating for handing out “great compassion” water

- Offering vegetarian meals

- Making offerings to ancestral tablets

- Promoting vegetarianism and protecting lives

- Preaching dharma and education

- Helping printing scriptures

- Discretionary donation

The embedded program combines the functions of providing religious services and working as an online donation channel, so that the monastery can still maintain connections with the public during the lockdown.

|

|

|

Figure 2: QR code for “online merit fields” at Zhuhai Putuo Monastery |

Figure 3: Twelve categories of “online merit fields” |

Two factors perhaps explain Putuo Monastery’s pioneer in using the social media. First, it is a new monastery established in a developed city on the east coast of China. In order to attract followers, it has the incentive to utilize WeChat, the most popular social media for the Chinese-speaking population.[2]

Second, its abbot, Master Mingsheng 明生 has the awareness to promote the monastery via WeChat. Master Mingsheng, who obtained a master’s degree, might have attracted a group of highly educated followers around him. Hence, it is not surprising for the affluent monastery to develop the online cultivation program.

Nevertheless, the effect of the online platform, the amount of participants, and the online participation still wait for more investigation in fieldwork in the future.

[1] Based on the numbers collected on the website: https://zt.pusa123.com/zt/30074.html

[2] According to Xinhua Agency, the number of monthly active users on WeChat reaches 1.151 billion in 2019. See http://www.xinhuanet.com/info/2020-01/10/c_138692663.htm.

Nan Ouyang is broadly interested in sacred space in East Asia, modern Chinese religion, and Chinese historical geography. Her dissertation examines the transformation of Mt. Jiuhua from a local attraction to a national pilgrimage destination in the late imperial and Republican eras. While at ARI, she plans to study Buddhism on Mt. Jiuhua during the Mao era (1949–1976) by using diverse materials including local archives. She studied in Shanghai, China and Tucson, the United States, and received her doctorate from the University of Arizona in the USA.

Disclaimer: The views and opinions expressed in this article are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the position of the blog editorial team or the Asia Research Institute.

South Asia | Southeast Asia | East Asia | Other Places | Hinduism | Buddhism | Islam | Christianity | Other Religions