From Field to Digital Ethnography: Observing Ritual Transformations in Singapore’s Historic Places of Worship

contributed by Lynn Wong, 23 June 2020

2020 was supposed to be a year packed with fieldwork for me. I have just completed conducting a season of Bicentennial Walking Workshops on historic places of worship and have spent the last quarter of 2019 establishing contacts with 11 kinship-based clan associations that are over 100-years-old to document their intangible cultural heritage (e.g., ancestral veneration rituals). I have marked on my calendar a series of religious and cultural events to document: (January - February) Chinese New Year celebrations, (March) a Clan Committee Inauguration Ceremony, (April) Qing Ming Festival and Birthday of Goddess of the Sea Mazu, (June) Duan Wu Festival, followed by many other upcoming events.

But alas, the Covid-19 pandemic thwarted plans.

The scenes on 7th Feb 2020 late afternoon remain fresh in my memory. Armed with my DSLR, I was taking in the colourful sights of Kavadi-bearers and the invigorating sounds of ceremonial music as the silver chariot made its annual grand procession from Sri Layan Sithi Vinayagar Temple at Keong Siak Road to Sri Thendayuthapani Temple at Tank Road. That was when I received the newsfeed notification on my phone: “Coronavirus outbreak: Singapore raises DORSCON level to Orange".

This is it. I swallowed hard and made a silent prayer.

Procession on the eve of Thaipusam. Photo taken by Lynn Wong on 7th Feb 2020

Experimenting new methods for digital ethnography

Over the following few weeks, fieldwork events on my calendar got struck off one after another. However, little did I expect my online “to do” list to grow longer and longer.

I began following the news diligently, and when Circuit Breaker made fieldwork difficult, I started a Facebook group to document the various regulations and happenings related to intangible cultural heritage. From news reports about the last joss stick maker in Singapore to donations at small religious sites running dry, it is apparent that such unprecedented times have made the livelihoods of already struggling cultural and religious practitioners even more difficult.

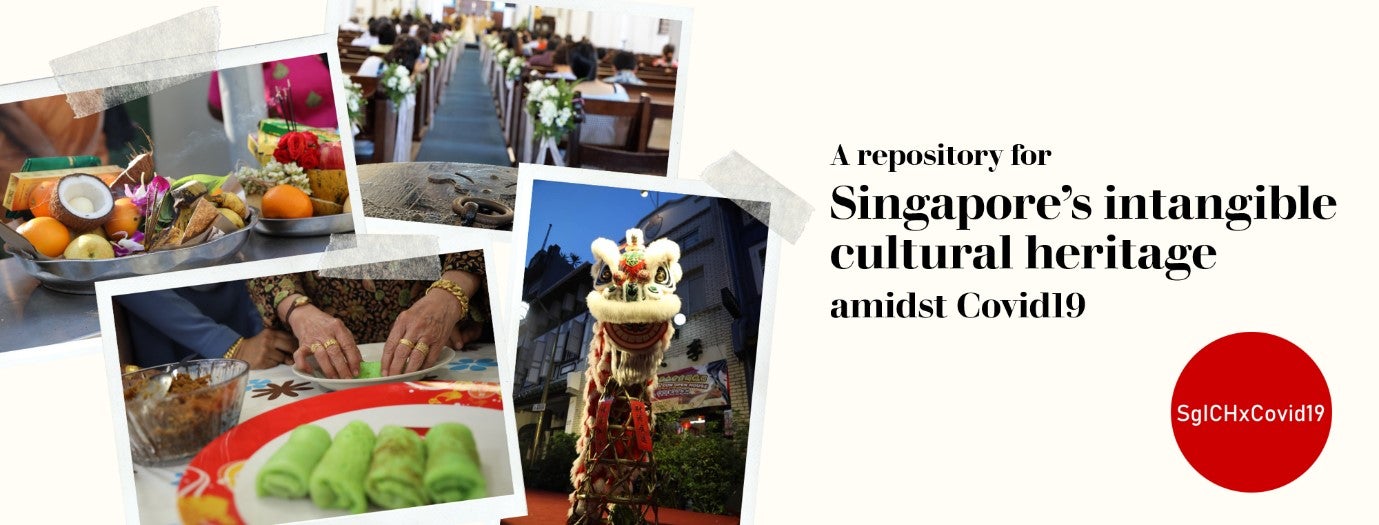

Even familiar religious rituals, which people of faith turn to for spiritual comfort in times of uncertainty, had to change. When all places of worship had to be closed, I initiated a #SgICHxCovid19 repository for the public to submit stories on how they kept their rituals, practices, and festivals alive albeit in adapted ways during the Covid-19 period. This idea sprang from a desire to understand other’s experiences from a first-person perspective during the pandemic, rather than having to rely solely on intermediary mediums such as the news which has become the main source of information about the “outside world” when staying home. It did not occur to me then that this was an experimentation with new methods to conduct digital ethnography.

A call for the public to share how they keep festivals, practices, and rituals alive during Covid-19 to the SgICHxCovid19 repository

At the start, there was little direction on how we can safeguard heritage during the pandemic in Singapore. There were many facets and complexities to grapple with, and regulations were constantly evolving with the pandemic. I was mentally “paralysed”. Then on 6 May, someone shared on the Facebook group I started: ICCROM Lecture Series “Protecting People & their Heritage in Times of COVID”. I was delighted! FINALLY. A series of online seminars to facilitate discussions and understanding on how other heritage organisations around the world are stepping up during the pandemic. This was exactly what I needed. The second webinar on “Heritage and Pandemics: Analysing an unfolding crisis” particularly inspired me. Here, different practitioners shared how they conducted situational analyses to understand the different facets that impact their heritage ecosystem. I remembered leaping onto my laptop immediately after the webinar. Thinking through my experiences working with different historic places of worship, I developed a 6R framework – a tool to conduct heritage situational analysis in Singapore. It is based on this 6R framework that I crafted my interview questions for stakeholders to understand how historic places of worship have been impacted by the pandemic. I will share some of these findings, particularly my “observations” of ritual transformations, in the next post.

Reflecting on the Pros and Cons

The pandemic presents exciting opportunities for researchers conducting digital ethnography. For one, more places of worship are making their services available online. This not only serves as good internal archival and documentation for the places of worship themselves, but it is also a resource which researchers can conveniently access and even refer to at a later date. This is especially true for spaces which one may previously have restrictions to access and must be there and then to observe. Secondly, with the proliferation of smart phones and more individuals uploading their personal practices online, researchers have greater access to diverse narratives. “Temple-hopping” various sites in a matter of seconds as in the case of e-Vesak this year as well as live-streaming Muslim families conducting prayers before breaking fast in their own homes, are just some examples.

On the other hand, there are many limitations to conducting digital ethnography. First, access to stakeholders without digital presence becomes ever more difficult. Ethnography requires a lot of trust building (which is often easier through face-to-face interaction) and unless strong rapport has been built prior, it is challenging to have them share their first-hand perspective on challenges and needs. Second, digital ethnography cannot replace the embodied experience in “traditional” fieldwork. Digital ethnography is ultimately still making observations through another’s lenses (figuratively and literally). Often, findings are made through keen attention to details during participant-observation (e.g., interactions among devotees, zooming in on specific offerings), which may not be captured by another’s lenses. Also, some things may be so normalised for the stakeholder (e.g., the scent of a site) that it is not mentioned or focused on unless asked specifically.

In conducting my research during the Circuit Breaker, I tried to overcome the above-mentioned challenges by complementing digital ethnography with phone interviews with stakeholders whom I have built strong rapport with in the past. As memories are fallible and many changes in regulations have taken place in a short span of time, I wanted to capture stakeholders’ perspectives as the pandemic unfolded while events are still fresh in their memory. Hence, a list of detailed questions covering the 6Rs in the framework I developed together with an appendix of the key dates/advisories were sent to interviewees beforehand, and the interviews were completed before Singapore’s gradual reopening on June 2.

Find out about my “observations” on ritual transformations in two historic places of worship on Telok Ayer in my next post.

Disclaimer: The views and opinions expressed in this article are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the position of the blog editorial team or the Asia Research Institute.

South Asia | Southeast Asia | East Asia | Other Places | Hinduism | Buddhism | Islam | Christianity | Other Religions

Lynn Wong is an independent researcher and filmmaker on a race against time to document and revive disappearing foods, festivals, and heritage in Singapore. She is also the co-investigator of Singapore Heritage Society’s two-year research project on 21 historic places of worship in Telok Ayer, Tanjong Pagar, and Tanjong Malang.