Japanese Folk Monsters for Covid Struggle: The Life History of a Yokai from Prophecy to Blessing

contributed by Lei Ting & Zhao Yuanhao, 30 July 2020

This post is an excerpt from an on-going research project. Please contact the authors before quoting.

On April 9, 2020, the Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare of Japan announced a mysterious creature named Amabie (アマビエ) as the official logo of the “STOP COVID-19” movement launched by the Ministry, in efforts to “inspire the youth” to help halt the pandemic.

Figure One: The official Amabie Logo made by the Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare of Japan. (https://twitter.com/MHLWitter/status/1248143633225666562)

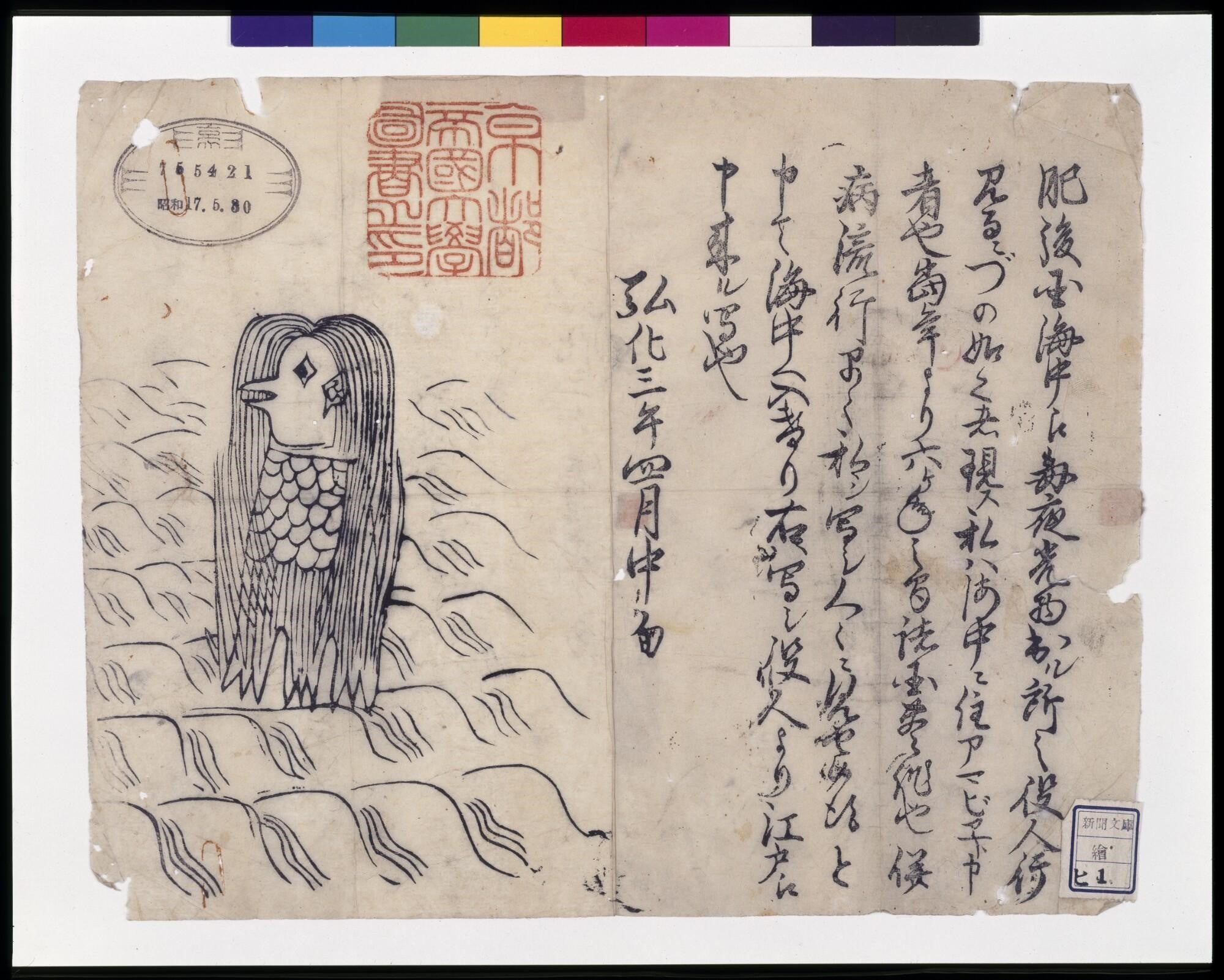

As a yokai or monster that was first created in the 19th Century, Amabie has suddenly become a phenomenon in cyberspace after the rampant spread of COVID-19 in Japan. As early as February 27, 2020, a Tokyo art shop dealing in hanging scrolls of the yokai declared that there was a yokai called “Amabie” in the 1800s, with a folk belief claiming its power of halting diseases. The shop then called upon people to spread the image of Amabie via social networking platforms (SNS) to help Japan stop the spread of COVID-19. On March 7, Kyoto University, where the earliest painting of Amabie is stored, posted on Twitter the photo of the original painting, or “surimono” of Amabie. “Surimono” (摺物) refers to one or several sheets of printing used in Edo Period to early Meiji Period to broadcast an incident or daily news.

Figure Two: Sea Monster of Higo Province (the Picture of Amabie), Collection of Kyoto University Library『肥後国海中の怪(アマビエの図) 』(京都大学附属図書館所蔵)https://rmda.kulib.kyoto-u.ac.jp/item/rb00000122#?c=0&m=0&s=0&cv=83&r=0&xywh=-9851%2C-1%2C29213%2C7622

The lines in this surimono read: “In Higo Province (now Kumamoto Prefecture), a glowing thing appeared in the sea at night. This creature in the picture then emerged when local functionaries went to check. It uttered the following words: ‘Residing in the sea, I am Amabie. Starting from this year, all provinces will have a succession of harvests for six years. While simultaneously, an epidemic will spread. Hurry and display my image to the people.’ After this utterance, back into the waves it submerged. The painting on the right was painted by the local functionary, it was then transmitted to Edo.”

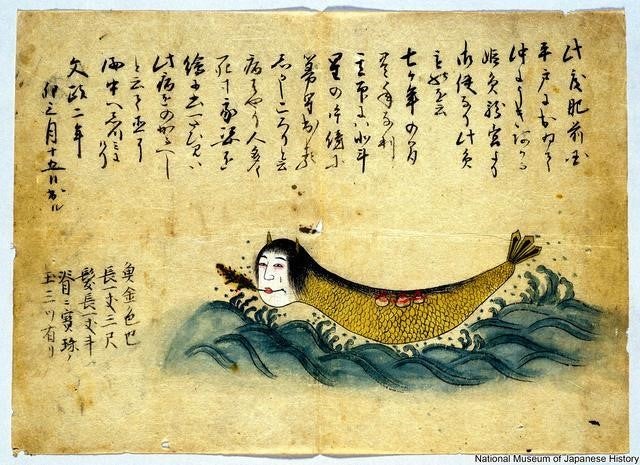

Figure Three: a Himezakana, or Princess-fish (https://www.asahi.com/articles/photo/AS20200508004451.html)

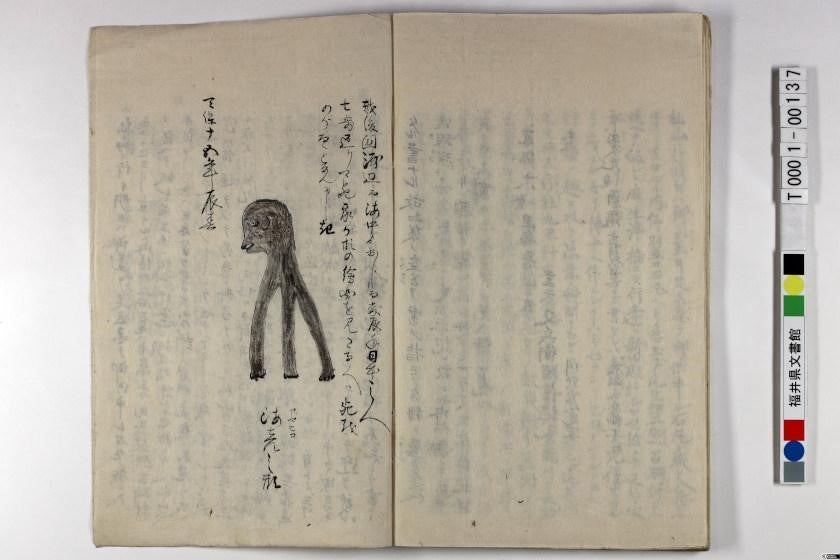

Actually, Amabie has various yokai comrades who also appeared around the mid-1800s making similar prophecies featuring both good harvests and upcoming disasters, and they all desired to be exhibited in paintings to help people halt bad luck, be it an epidemic or another calamity. For instance, see the Himezakana of Hizen Province (now Nagasaki Prefecture) and the Amabikoi of Echizen Province (now Fukui Prefecture).

Figure Four: an Amabiko (https://fupo.jp/article/amabie/)

In general, during the late Edo Era, these mysterious creatures gradually ceased to live a different life in every specific experience or have a different appearance in each particular mind, but became re-contextualized with relatively fixed features such as three legs and long hair, being prophetic, residing in the sea and so forth. And the narratives are quite similar too. The dynamics behind people’s preference over Amabie in contemporary Japanese society are complex - here we present one thread of it.

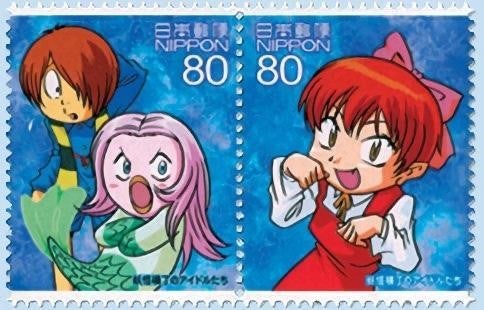

Figure Five: Amabie Girl (long hair with fish-tail) on a special postage stamp for GeGeGe no Kitarō (https://twitter.com/kitteclub/status/1253881748913455105)

When the Late Japanese manga artist Mizuki Shigeru depicted traditional Japanese yokai in his work GeGeGe no Kitarō, he chose to creatively re-forge Amabie to “help” it choose the way it appears and appeals to the public. His original painting was further developed in 2007: when a prophetic character was needed in the story of the newly produced anime GeGeGe no Kitarō, an Amabie character made its debut in the series in the form of a cute girl who seeks popularity. This remarkably re-contextualized the character and established its image in people’s minds, especially amongst the anime audiences. By contributing to a product (anime) based on former folk belief (yokai), Amabie has become a “folkloresque” element, or “popular culture’s own (emic) perception and performance of folklore” (Foster 2016, 4) in the contemporary yokai culture industry, and has hence maintained this role in the later COVID-19 period.

Recently in Japan, Amabie has become an officially recognized sign of people’s willingness to overcome COVID-19. The authors would be cautious to claim the return of a folk belief in Amabie. However, it will be safe to argue that the awareness of a former folk belief has been revived to some extent. Only now, instead of holding the belief in Amabie’s power to terminate the spread of COVID-19, many people may only be utilizing the image of this creature to express their willingness and emotions in public space. However, this does not mean that Amabie has no religious meaning. Rather, it has been incorporated into long-established and privileged religious spaces in Japan, such as some Japanese Shinto shrines and Buddhist temples. For instance, on May 25, a 115cm-tall wood carved Amabie was set up for people to worship in the Isahaya Shrine, for which the latter was established in 725 CE in Nagasaki Prefecture.

Figure Six: Amabie Figure of Isahaya Jinja Shrine (https://isahaya-jinja.jp/amabie-mokuzou-no1-hounou/)

Yokai has traditionally been part of Japan’s everyday cultural practices. As aforementioned, Amabie’s role of being a folkloresque element in yokai culture events has also been preserved. If one could say anime and postage stamps reinvigorated Amabie’s presence in Japan’s contemporary popular culture, under the circumstance of COVID-19, Amabie’s popularity only continued to skyrocket on SNS platforms such as Twitter, as many activities have been initiated and shared, enabling recreations and representations of this creature in vernacular cultural practices. These activities in turn contributed to the visibility of Amabie as a social phenomenon. On a personal level, people also use the image of Amabie in vernacular art practices, such as using stylized images of the yokai on handcrafted objects. Not surprisingly, Amabie also finds its way into commodities. Some traditional Japanese sweets shops have started to make Amabie-shaped confectioneries, and breweries have invented new designs featuring Amabie on beer bottles.

Figure Seven: Amabie on beer bottle (https://www.sanktgallenbrewery.com/AmabieIPA/)

To briefly summarize, this post explored several stages in Amabie’s life, from a suspicious creature that prophesied catastrophe, to a de-contextualized anime character, all the way to its current representation. Amabie is now ‘brought to life’ and re-contextualized in the Covid-19 pandemic, and this time it appears clearly as a symbol of blessing in Japan.

References:

Foster, Michael. 2016. The Folkloresque: Reframing Folklore in a Popular Culture World. Utah State University Press.

Lei Ting (graysadness@gmail.com), PhD candidate of Tokyo University, her research field covers folklore study, vernacular art, and representation and self-expression of rural population in China, especially “Jinshan Peasant Painting,” Shanghai.

Zhao Yuanhao (zhyuanhao@gmail.com), PhD of the Ohio State University, he is interested in Muslim study, material culture, and narrative study. His recent projects include personal narrative and death related folklore in China’s Hui Muslim minority’s everyday life.

Disclaimer: The views and opinions expressed in this article are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the position of the blog editorial team or the Asia Research Institute.

South Asia | Southeast Asia | East Asia | Other Places | Hinduism | Buddhism | Islam | Christianity | Other Religions