‘We knew it!’ - Caribbean Hindu Responses to Restrictions of Touch during COVID-19

contributed by Sinah Theres Kloß, 28 October 2020

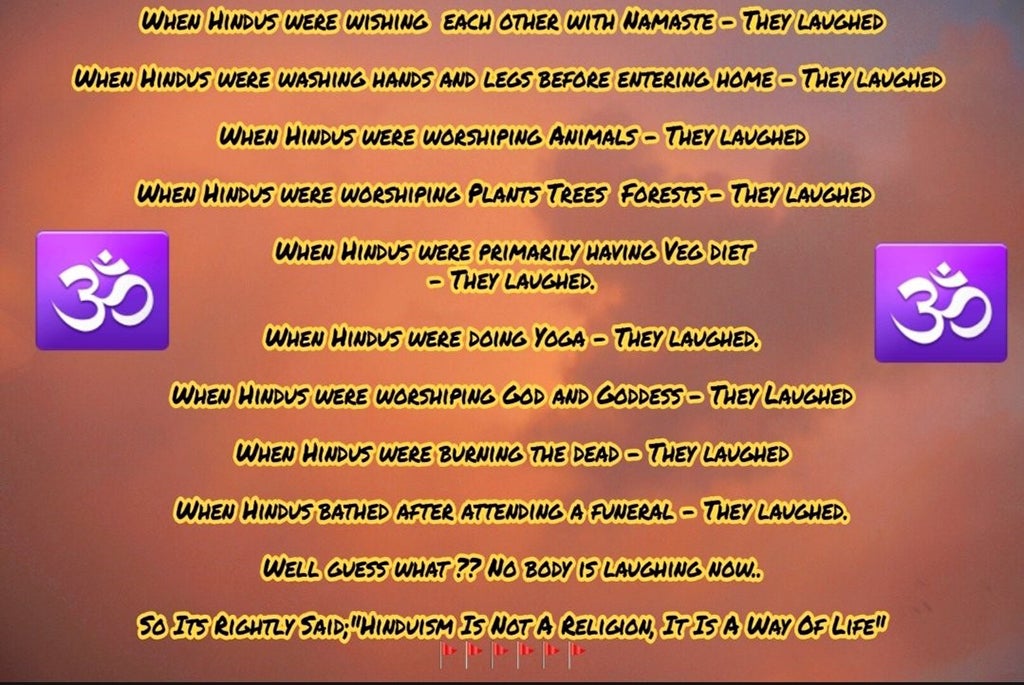

On March 16, 2020, I received a message on social media from some of my Surinamese and Guyanese Hindu friends, who shared an image file that commented on the hygienic precautions and regulations enforced in an increasing number of nation-states during the emerging COVID-19 pandemic. The images and backgrounds varied and had been adapted to personal taste, including Hindu symbols such as the Aum sign or depictions of Hindu deities. They generally included the following text (in reference to figure 1 below):

“When Hindus were wishing each other with Namaste - They laughed

When Hindus were washing hands and legs before entering home - They laughed

When Hindus were worshiping Animals - They laughed

When Hindus were worshiping Plants Trees Forests - They laughed

When Hindus were primarily having Veg diet - They laughed.

When Hindus were doing Yoga - They laughed.

When Hindus were worshiping God and Goddess - They Laughed

When Hindus were burning the dead - They laughed

When Hindus bathed after attending a funeral - They laughed.

Well guess what ?? Nobody is laughing now..

So Its Rightly Said; “Hinduism Is Not A Religion, It Is A Way Of Life”

(Author unknown)

Figure 1: Message circulated on social media in March 2020

The text itself and its related images were widely shared on social media, not only among Caribbean Hindus, but Hindus worldwide. In India, particularly Hindu nationalist groups seemed to have circulated the text within their community. In the Caribbean, Hindus forwarded the message to show their pride in being Hindu, which has to be contextualized in post-indentureship societies, where Hindus have been experiencing stigmatization and marginalization as followers of a minority religion for over a century.

Caribbean Hindu Claims to Superiority

In the predominantly Christian colonial societies of the then British and Dutch Guiana, Christianity was linked to the notions of “civilization”, “education”, and “respectability”. From the perspective of the colonizers, only Christians were considered to be “civilized” while Hindus were declared as “uncivilized” and “backward”, hence inferior (Williams 1991; Vertovec 1994; Kloß 2016). Consequently, Hindus have been subjected to and concerned with Christian efforts of proselytization ever since the arrival of Indian indentured labourers in the Caribbean between 1838 and 1917. Even today, some of them express the need to constantly justify and defend their practices and beliefs in light of the dominant Christian ideals.

Not all Caribbean Hindus accept this stigmatization, however; some actively challenge it by emphasizing the sophistication and authenticity, and hence superiority, of Hinduism. In their efforts, they are increasingly supported by conservative Hindu nationalist ideologies, promoted in diasporic Hindu communities worldwide. In the Caribbean, discourses of Hindu superiority and the proclamation of “greater” knowledge in comparison to Christianity are commonly used to contest and subvert the local socio-religious hierarchy and notions of respectability (Kloß 2017).

In this context of marginalization, my Caribbean Hindu friends shared the image files as a comment on COVID-19 measures around the globe in general, but also as a means of claiming (global) Hindu superiority. The message itself listed nine socio-cultural norms and practices that are said to be among the central aspects of the Hindu “way of life”. By proclaiming that – unlike Christianity – Hinduism is not a religion, but a way of life, Caribbean Hindus often emphasize the “truthfulness” and “authenticity” of Hinduism in opposition to other “religions”, in particular Christianity.

For instance, during my ethnographic fieldwork between 2015 and 2017, many Guyanese Hindus referred to “religion” as a kind of orthodox structure that is imposed on a community and “cast upon” people (Kloß 2020). They understood “religion” as something formal and inauthentic. On the contrary, they referred to “spirituality” as a “way of life”, suggesting that it emanates “from within” a group or person. Hinduism, as a kind of spirituality and way of life, is considered more “natural” and “authentic” than Christianity, as it was not imposed on Indians during colonialism, and affects all aspects of a person’s life.

With regard to the “When Hindus…” text and images, the statement that Hinduism is a “way of life” thus may be understood as a challenge to Christianity and, more broadly, to the “West”, which they often generalized as Christian.

Bodies, Touch, and Pollution in Hinduism

All practices referred to in the message were related to notions of pollution, (im)purity, hygiene, and touch. While even non-Hindus can easily relate some practices – such as bathing, washing, and the burning of the dead – to “hygiene” or precautions during the pandemic, other references require more contextual knowledge.

For example, the practice of “wishing each other with Namaste” refers to the customary Hindu greeting, during which a social actor presses his/her/their hands together, fingers pointed upwards and palms touching. During this greeting, no contact occurs between the different parties involved. As no inter-body contact is established, the risk of (pathogen) transmission is hence minimized.

Figure 2: Statue of a famous, late head pujari (priest) in a Guyanese Hindu temple, his hands folded to the Namaste greeting. Photo by Sinah Kloß, Guyana, September 2017

From a Hindu perspective, the polluting capacity of the “Western” handshake is obvious – and not only in times of COVID-19: all bodies are considered to be “polluted” to varying degrees. Additionally, bodies are conceptualized as permeable and open (Böhler 2010), divisible or “dividual” (Marriott 1976). They are perceived as constantly emitting substances, particles, and energies into their surroundings, and they simultaneously receive substances and energies from other emitting entities.

While such transmission may occur without direct contact, physical touch is thought to concentrate the flow of substances and energies, intensifying the exchange. Tactility thus is considered a particularly effective and influential mode of exchange, with either negative (“polluting”) or positive (“purifying”) implications.

Figure 3: Hindus touching shoulders while offerings are made to a deity. Through this physical touch, auspicious energies and substances are transferred to all touching parties. Photo by Sinah Kloß, Guyana, September 2017

The shared message suggested that although Hindus have been ridiculed for their greeting practices in the past, during COVID-19 even non-Hindus have finally realized that the Namaste greeting is indeed a “better”, “cleaner”, and “healthier” mode of greeting. By sharing the “When Hindus…” text and images, Caribbean Hindus have challenged the allegedly higher status of “Western”/Christian practices and knowledge, claiming superior knowledge and status in local and global social hierarchies.

Regimes of Touching

Restrictions and regulations of touching and not-touching have always been influential and relevant in Hindu concepts, hierarchies, practices, and rituals; one only has to think of the category of the “untouchable”. But COVID-19 has drastically brought to the awareness of Hindus and non-Hindus alike that human touch and the regimes of touching are part of all (national and local) body politics, and are intrinsic aspects of biopower. COVID-19 has changed the perception and recognition of the relevance of touch with regard to public health, resulting in adaptations of safety measures and modes of surveillance.

On a more general level, the significance of touch and regimes of touching have always been relevant to the construction of society and social relationships, not only since the emergence of COVID-19. As such, they should no longer be marginalized but treated as highly significant research areas, and should be the focus of more contemporary research, supported by research funding.

References

Marriott, McKim. 1976. “Hindu Transactions: Diversity Without Dualism.” In Transaction and Meaning: Directions in the Anthropology of Exchange and Symbolic Behavior, edited by Bruce Kapferer, 109–42. ASA essays in social anthropology. Philadelphia: Institute for the Study of Human Issues.

Sinah Theres Kloß is leader of the research group “Marking Power: Embodied Dependencies, Haptic Regimes and Body Modification” at the Bonn Center for Dependency and Slavery Studies (BCDSS), University of Bonn, Germany. She holds a PhD in Social and Cultural Anthropology from Heidelberg University.

Disclaimer: The views and opinions expressed in this article are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the position of the blog editorial team or the Asia Research Institute.

South Asia | Southeast Asia | East Asia | Other Places | Hinduism | Buddhism | Islam | Christianity | Other Religions