Buddhist Temples as Shelters for Vietnamese Migrants in Japan under COVID-19 Conditions

contributed by Yuki Shiozaki, 16 March 2021

Cover image: Relief supplies collected for the Vietnamese in Japan. Nihon Keizai Shimbun, 30 May 2020

When the Japanese economy faced depression in 2020, one of the most affected groups in Japanese society were the foreign workers. Shrinking economic activity resulted in layoffs, and foreign workers were the first employees to be dismissed from many companies. These retrenchments were disastrous for 80,000 Southeast Asians residing in Japan. For those without public aid, religious institutions provided a social safety net.

As in other societies, the COVID-19 pandemic intensified prejudice against minorities, especially migrant workers. They were frequently assumed to be the source of infection despite a lack of evidence. At the same time, many Japanese also considered places of worship suspect, especially after it was reported that Christian churches in South Korea and mosques in Malaysia had become clusters of infection. Therefore, as a consequence, the religious facilities of these immigrant workers were regarded as potential clusters and forced to restrain activities.

Japanese society has become increasingly secular. The role of religious institutions in social life is now largely limited to the provision of rituals such as funeral services. During the COVID-19 pandemic, few Japanese appealed to Buddhist temples and Shinto shrines for divine protection or intercession. Most Japanese felt that the government and scientists were best equipped to handle the pandemic. However, the situation differed amongst Southeast Asian immigrant workers. In many cases, they were abandoned by their employers and the government - hence turning to religion for a pillar of support. While most religious institutions were forced to curtail their activities, with a corresponding dip in revenue, some sought to accumulate social capital by catering to the needs of these migrant workers.

The Rapid Expansion of Southeast Asian Communities in Japan

Due to the increased reliance of Japanese industries on foreign workforce since the 1990s, there is estimated to be 1.5 million foreign workers in Japan in 2020 (Table 1), with most hailing from China and Southeast Asia. Even though foreign workers’ period of stay is limited to several years, a regular influx of migrant workers has changed the demographic landscape of certain areas in Japan. Newly established religious facilities are part of such new exotic scenes. Filipino churches, Indonesian mosques, and Vietnamese Buddhist temples have been established especially in the area around Tokyo and Nagoya, and they function as community centers for the Southeast Asian nationals.

|

Nationality |

Number of Registered Residents |

|

Vietnam |

420,415 |

|

Philippines |

282,023 |

|

Indonesia |

66,084 |

|

Thailand |

53,344 |

|

Myanmar |

33,303 |

|

Cambodia |

15,656 |

Table 1: The residents from ASEAN countries in Japan in December 2019. Data retrieved from the Statistics of Foreigners Residing in Japan, Ministry of Justice, Japan.

Religious Facilities as Hubs of Aid Distribution during the Pandemic

Since the state of emergency was declared by the Japanese government in April 2020, these religious facilities had to implement curbs on their normal activities to manage the risk of infection. Congregational prayers and religious celebrations were of particular concern. The closure of religious facilities to the public resulted in the loss of a communal space for Southeast Asians, compounding the social isolation they were already experiencing.

Even though religious facilities’ functions as community centers were limited under the state of emergency, such places of worship became the last refuge for many jobless Southeast Asian workers. Foreign workers, especially those without jobs and fixed addresses, did not qualify for public aid. Repatriation flights were canceled or became too expensive for them. As such, many displaced workers were absorbed into underground communities or criminal syndicates to survive. Fortunately, some of the dismissed foreign workers without means of sustenance were helped by religious groups, which opened access to places of worship, and even provided living necessities and shelters for them.

The Catholic Church became a node within a support network for Filipino and Vietnamese Catholics in Japan. In many Japanese Catholic churches, especially in urban and industrial regions, Filipinos and Vietnamese have come to constitute the majority of worshippers since 2000. Japanese Catholics were estimated to number 440,000 in 2020, and there existed a similar number of Southeast Asian Catholics in Japan. The Catholic churches in areas where Southeast Asian Catholics were concentrated became sites for the collection and distribution of relief supplies during the COVID-19 pandemic (Nihon Keizai Shimbun, 30 May 2020).

Figure 1: Father Joseph Nha dispatching relief supplies. Nihon Keizai Shimbun, 30 May 2020. (Screengrab by the author)

Prefectures around Tokyo, especially Gunma and Saitama, became destinations of dismissed Vietnamese workers in recent years. In depopulated areas of these prefectures, there are significant communities of jobless Southeast Asians, mostly Vietnamese. Because they have a very limited means to survive once they have been dismissed by their employers, and the administration is unable to locate them, their growing presence has become a serious concern in these areas. In Saitama, out of the 433 foreigners arrested by the police in 2020, 212 were Vietnamese workers. Most of them were arrested on charges of larceny including thefts of livestock and agricultural products from local farms (Jomo Shimbun, 7 February 2021). Large-scale theft from farms in the nighttime became a social problem on the outskirts of Tokyo.

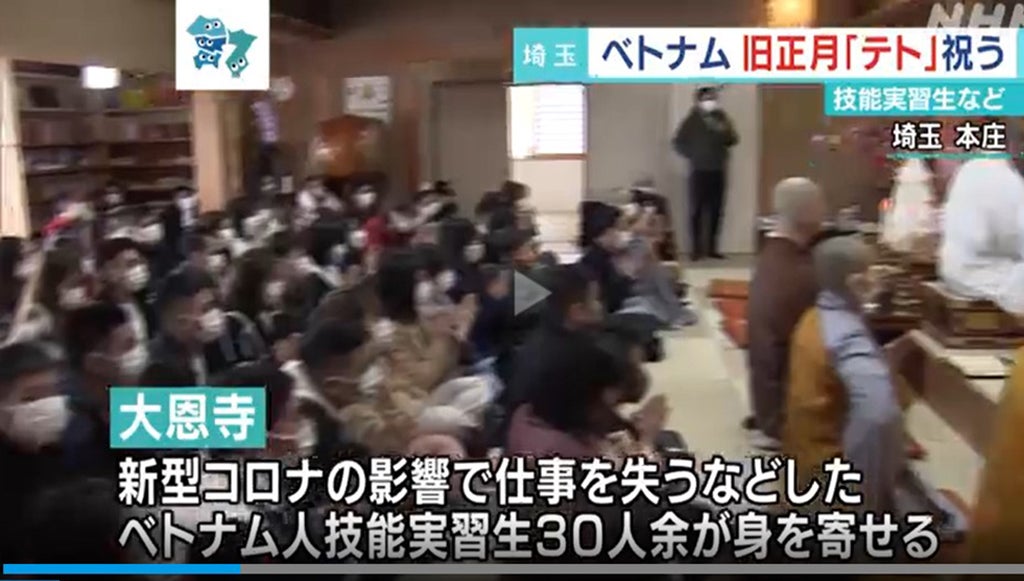

A Buddhist temple, Daionji, has also played a role in aid distribution during the pandemic. The temple was established by a Vietnamese nun named Thich Tam Tri in Saitama in 2018. When the Vietnamese community in Japan expanded rapidly in the 2010s, there was also an expansion of demand for Vietnamese Buddhist temples as places for communal gathering and for holding religious rituals such as funerals. During the height of the COVID-19 pandemic in 2020, Daionji provided shelter for jobless and homeless Vietnamese. Dozens of young Vietnamese resided in the temple. Their foodstuffs and living expenses were supplied by the Vietnamese community and Japanese Buddhist devotees.

Figure 2: The Vietnamese staying in Daionji celebrated Tet or Vietnamese Lunar New Year. News program by NHK on 12 February 2021. (Screengrab by the author)

Another Buddhist temple in Nagoya, Tokurinji, also provided shelter for dismissed Vietnamese workers. Generally, the majority of Japanese Buddhist temples are financially sustained by local communities and hence only open for community members. However, Tokurinji was an exceptional case among the contemporary Japanese temples. Even though Tokurinji was a traditional Zen Buddhist temple, the Japanese priest of the temple accepted dozens of young Vietnamese. The temple transformed into a community to live, work and study in while the Vietnamese waited for opportunities to return home.

Figure 3: The priest of Tokurinji working with the Vietnamese youth. News program by Tokai TV on 22 September 2020. (Screengrab by the author)

Religious Facilities as Distinctive Social Capital in a Secular Society

For most Southeast Asian migrant workers who lost their jobs in 2020, there were few options other than being absorbed into the underground communities of overstaying residents. The Japanese administrations have evinced a lack of interest in them, and have little intention to aid them with public money. Only some Buddhist temples and Christian churches provided unconditional aid to migrant workers, despite their limited capacities. Although thousands of Vietnamese have nowhere to go, each temple and church can take care of scores at most. In epidemiological terms, however, it is too risky to simply abandon thousands of dismissed migrant workers. The costs - in the form of further COVID-19 outbreaks - will be borne by both the Southeast Asian community and Japanese society at large. The temples and churches play a significant role as mediators between the forsaken Vietnamese and the Japanese society, even though the majority of Japanese religious facilities only serve the local native Japanese communities and tend to ignore the foreign migrants. Their contribution shows religious facilities can provide significant and much-needed social capital, particularly when it is not provided by the government in contemporary Japan.

Disclaimer: The views and opinions expressed in this article are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the position of the blog editorial team or the Asia Research Institute.

South Asia | Southeast Asia | East Asia | Other Places | Hinduism | Buddhism | Islam | Christianity | Other Religions

Yuki Shiozaki is an associate professor at the School of International Relations, the University of Shizuoka in Japan. He works on Islam in Southeast Asia. His research interests include historical interactions between Southeast Asia, the Middle East, and Southeast Asia. He has published articles on Islamic scholars, Islamic literature, and religious interactions in Southeast Asia.