#IAMHUSSEINI: How the Covid-19 pandemic reinforced a global Shi’a community

contributed by Rhys Thomas Sparey, 12 August 2021

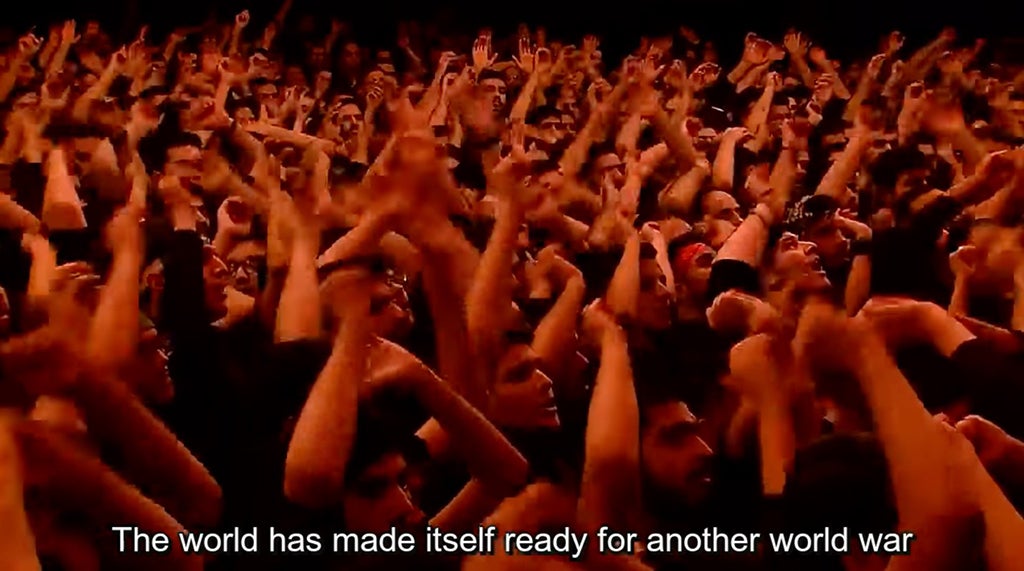

Cover image: #IAMHUSSEINI television program 2020. Source: Imam Hussein TV, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=B-6RZW8uQKw&t=1117s

This blog post focuses on a talk show titled #IAMHUSSEINI to describe how the Covid-19 pandemic impacted members of the Shi’a religious community, a group that transcends national boundaries, maintains a tight connection between the personal and collective facets of the faith, and is already involved in digital religious activities. Using the example of Ashura, I will describe this commemorative event, and compare its pre- and post-pandemic digital versions.

The Remembrance of Hussein

During Ashura, Shi’as remember Imam Hussein Ibn Ali, who was killed in the Battle of Karbala for trying to meet supporters who offered to overthrow the caliph. Shi’as believe the leader of the faithful should be a descendent of the Prophet Muhammad PBUH whereas the Sunni Muslims who led the first caliphate did not believe that the prophet designated a successor, leaving the role open to the winner of an election.

The death of Hussein in 680 CE was upsetting for three reasons: his family lost a relative, all Muslims lost a descendent of the Prophet, and Shi’as lost their imam, along with the ideal of inherited leadership he personified, which Shi’as understand to be sacred. In fact, legend has it that Zainab, Hussein’s sister, grieved for him by beating her chest and weeping. Due to Zainab’s holy lineage, her method of mourning became a tradition that would outlast the pre-Islamic custom of grieving by beating the chest, such that it is now unique to the ritual memorialisation of Hussein.

The remembrance of Hussein is a deeply multifarious occasion. On the one hand, it is pertinent to the whole of Islam since Hussein is revered as the son of one of the rightly guided caliphs. Indeed, part of the point of the commemoration of Hussein is to advertise through public mourning and martial symbolism a version of Islam that Shi’as believe is truest to its teachings. On the other hand, Ashura takes on a uniquely Shi’i essence, in that Shi’as feel the need to assert the distinction between an observance of Islam that respects the tenet of a divinely ordained religious leader and the Sunni version, and this is often a politically charged assertion.

Figure 1: Hezbollah fighters drive motorbikes in an Ashura procession in Seksakiyeh, Lebanon. Source: https://www.dawn.com/news/1289492

Politics and the Performance of Distinction

During Ashura, Shi’as perform their distinct identity in myriad ways. Musically, there is a disjuncture between the tonality of the recitation of the types of poetry that commemorate Hussein (nūḥa and marsiyya) and the topics of the poems mourners recite during Ashura. Raga are widely recognised as part of an Indian classical tradition, involving selections of notes with their own conventions for being used. For a historically Iraqi tradition to occur via Indian music suggests a important difference between the geographic indexes of religious identity for Islam as a whole and Shi’a Islam specifically.

Muslims are required to pray five times per day in the direction of Mecca, a city in Saudi Arabia. To musically indicate a different location, India, by way of raga, is a radical departure from the geopolitics of Sunni Islam. Moreover, the annual speech of the Grand Ayatollah of Iran is often listened to by millions of Shi’as each year, reflecting fraught political differences between Iran and Saudi Arabia, and the religious communities they respectively represent and repress. This distinction can also be architectural. An assembly of worshippers in Islam is known as a majlis. During Ashura, the majlis assembles, if not in public, then in a building usually named an imāmbāṛa.

The prevailing architecture globally is the Persian model, a quadrilateral congregation hall with a mezzanine in one large room from which women can observe male elegists at a distance. These are catered to local frames of reference for archetypes of Shi’a identity. One archetype is the warrior, symbolising the bravery of Hussein, who is said to have travelled unnamed despite knowing the futility of his endeavour. The main frames of reference for warriors in India are rajput families, denoting castes and lineages linked to an ethos of bravery and skill in combat. Memorial halls across south Asia thus bear an unsurprising resemblance to the baradari, a pavilion associated with rajput architecture.

Figure 2: Prithviraj Ki Kutcheri is a baradari said to have been commissioned by the rajput king, Prithviraj Chauhan, in the twelfth century in Haryana. Source: https://haryanatourism.gov.in/Destination/prithviraj-ki-kutcheri

Figure 3: The Chhota imāmbāṛa in Uttar Pradesh bears many of the architectural features of Prithviraj Ki Kutcheri on a grander scale; pointed archways punctuate the perimeter of the building, an ornate dome tops the centre of the roof, and a middle entrance area protrudes outwards. Source: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Chhota_imambara_Lucknow.jpg

Empathising with the Martyrs

Each of these descriptions of the mourning of Muharram—architectural, musical, and otherwise—amount to a religious practice that is personal and collective instantaneously, and on varying levels, because it is both a generally Muslim religious practice and a specifically Shi’a political practice. This is not to reify an opposition between religious and political dimensions but to emphasise that neither category sufficiently explains their coalescence in Ashura. However, the missing piece of the puzzle, which will help to formulate a coherent explanation, regards the way in which Shi’as come to express their faith politically, which transpires primarily through empathy.

A prevailing theme of nūḥa and marsiyya poetry is “overcoming”. The Safavid Shah, Abbas the Great, for instance, invoked the memory of Zainab before battling his sworn Sunni enemies, and this sense of overcoming is not unique to historic military leaders either. For instance, a practitioner (interviewed by phone on 17 November 2019) told me that increased volume was a way of “being heard when they are trying to keep you quiet,” citing the curfew instituted by the Indian government to prevent revolt following the revocation of the region’s special status, and the overcoming of the various constraints it entails through the recitation of poetry during Ashura.

Concomitantly, “song[s] about enemies of Iran” have been uploaded onto the internet (figure 5). In one example, the anonymous publisher describes the nūḥa as “an Iranian song… about their readiness for a war against [the] USA, Saudi and Israel.” In the video, the elegist recites the phrase “terror, corruption, and hypocrisy are united against us” and compares Imam Hussein and Ruhollah Khomeini. Meanwhile, numerous respondents hold their hands out in the direction of the elegist who chants beneath the national emblem of Iran and shouts “Haydar,” a nickname of Hussein’s father.

While the former and latter example may be respectively more against and in favour of a nationalist ideology, they both demonstrate how a worshipper empathises with Hussein by bringing to the fore their own experiences of overcoming and oppression. Some worshippers may also empathise with the suffering of Hussein in a more visceral and embodied way, such as through dehydration and self-flagellation. This subjective feeling is articulated collectively, as a majlis, in reference to numerous other collectives, such as the nation, Shi’a Islam, and so forth.

Figure 4: A still from a video titled “Nohe Song about Enemies of Iran (English Subtitles)”. Source: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=EGBZold3-qI

Ashura during the Covid-19 Pandemic

What happened to the celebration of Ashura during the Covid-19 pandemic? While Ashura is usually a large and crowded public event, in the interests of public health and hygiene, restrictions on gatherings were put in place. Some ceremonies became live streamed on social media and others found creative ways of social distancing while mourning. For example, in one case, worshippers were themselves sprayed with disinfectant before they could proceed with the commemoration (figure 6)! But, what about Ashura rituals that were already digital and socially distanced? How did they change during the pandemic?

Figure 5: Ashura mourners are sprayed with disinfectant before a ceremony. Source: https://www.middleeasteye.net/news/coronavirus-ashura-shia-worshippers-amidst-pandemic

Imam Hussein TV

Since 2009, the year Imam Hussein TV was founded, Ashura has been televised. Every part of the pilgrimage to Karbala is captured and broadcast on screen. Additionally, in order to reduce the risk of losing the sense of community brought about by the physical majlis, the TV channel instituted a special “Welcome to Karbala” programme, a predecessor of the 2019 “#IAMHUSSEINI” programme. Saturated with red, the set evokes the blood shed by Hussein before a glass panorama revealing his tomb and the hundreds of green-cum-red lights that envelope the streets of Karbala. The upset of the show’s interlocutors--hosts, guests, callers--conveyed through elegies obfuscated by crying, are transmitted to an international audience, taking the shape of a call-in talk-show.

There are some notable differences between Welcome to Karbala before the spread of the novel coronavirus and #IAMHUSSEINI during it. The host of the latter, for instance, wore traditional mourning attire in contrast with the former host’s suit, indicating that the channel had decided to try to symbolize more formal and orthodox forms of worship. During Welcome of Karbala, the hosts promised to pray for the viewers that rang in. This year, one could see their names written on a flag of Hussein, incorporating them into an explicitly represented televisual majlis. During #IAMHUSSEINI the host played on the narratives of oppression that take centre stage during Ashura, and added to it the conditions of the Covid-19 pandemic, stating that “the pandemic has tried to prevent us… but I see the love for Hussein. … Covid-19 has tried to prevent the zuwār [visitors] of Imam Hussein, but… [it] took the upmost precautions, stood there with their face masks…. [and their] face shields… [and] brought servants of Imam Hussein out with sanitisation… cleansing the air…”

Callers could utilise #IAMHUSSEINI however they saw fit. Mohammad, the inaugural caller of the show was grateful that “by the grace of Imam al-Mehdi [the unknown living Imam], we are able to come here and commemorate and renew our allegiance.” For Mohammad, #IAMHUSSEINI meant performing a solo recitation of the kind that might be heard at a majlis, linking his individual emotionality to the collective experience of an indeterminate “we.” Another caller admitted that “whenever I sleep, whenever I wake up, I feel that I am far, but my soul is there… It is so sad, you know? I am sitting beside the TV. I am watching.” The personal nature of their comments differs from Mohammad’s. Theirs is about the “I” and a sense of physical distance from a place of worship that intensifies their sorrow, but their soul, they say, is in Karbala, relating to their engagement with the television programme and the implicit solidarity they feel with a community of remote practitioners.

One may also have discerned from its title that the show’s interlocutors were not always audible. #IAMHUSSEINI has placed a hashtag at the forefront of its branding. This makes it possible for social media users to signal their consumption of the programme and any lived experience relevant to its content. This method of interacting with #IAMHUSSEINI has not yet achieved much popularity. At the time of writing, only Imam Hussein TV have used the hashtag, but it demonstrates another way in which the television channel is endeavouring to digitise and expand ways of mourning in Muharram, in light of the challenges posed by the Covid-19 pandemic.

By capitalising on their new audience’s thirst for the in-person rituals they were deprived of, Imam Hussein TV lost its subversive, distinctly digital flavour. It reverted to more orthodox modes of worship, it mobilised devices for visually reminding callers of the community to which they belonged, and it incorporated the coronavirus into the overcoming narrative on which Ashura is based, and it was more popular than it ever had been before. In fact, rather than individuating practitioners, the effect of the Covid-19 pandemic was to bolster the community spirit of the Imam Hussein TV viewership, a televisual majlis unto itself.

Figure 6: Welcome to Karbala in 2017, courtesy of Imam Hussein TV: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=rVjczE42z4A&t=1053s

Disclaimer: The views and opinions expressed in this article are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the position of the blog editorial team or the Asia Research Institute.

South Asia | Southeast Asia | East Asia | Other Places | Hinduism | Buddhism | Islam | Christianity | Other Religions

Rhys is a doctoral candidate in the music department at King’s College London. He is interested in the cultural history of the Arabian Sea in the digital age, with a focus on the study of Islamicate modern art and technology from a transnational perspective. His PhD dissertation explores the arts and rituals of Ashura.

Other Interesting Topics

Forest People Confronted by COVID-19: Representations, Rituals and Practices of Pala’wan Highlanders

The Pala’wan Highlanders form a small egalitarian forest society living in the island bearing the same name in the Philippine archipelago. The habitat of these hunters equipped with blowpipes, gatherers and shifting agriculturists is scattered, forming small hamlets separated by valleys around Mount Mantalingahan...

Spiritualizing Confinement and the Rise of Meditation Apps

A quick look at the last posts published on our blog CoronAsur will suffice to state that numerous religious communities have employed all the technologies at their disposal to livestream rituals and host online gatherings, in a ‘virtual’ as opposed to ‘physical’ realm. These phenomena have...

Hosting a God’s Birthday Party during Covid-19

Singkawang, West Kalimantan is a small city with a majority Chinese Indonesian population in Borneo. It is a center of Chinese Religion and called the “City of a Thousand Temples''. My ongoing research confirms that there are over 250 temples, including large denominations of international Buddhist as well as smaller temples venerating specific gods...