States of Statelessness for the Rohingya

https://doi.org/10.25542/m5h6-r971

In Ramadan this year, a longtime Rohingya friend hosted me and some members of the Rohingya community in Kuala Lumpur for one of their special iftar dinners. The meal was a sumptuous affair of various ethnically Rohingya dishes, and my host took the time to introduce each to me, from the exceedingly spicy chicken mix to the staple Rohingya chickpea stew, while insisting that I take second and third helpings even though I was beyond full. Interestingly, while we waited for the meal to be served, I noticed the host’s children in the background and asked if they could speak Malay, the local language, to which he replied, “No.” My curiosity sparked, I followed up by asking further whether he expected that they would see themselves as more Rohingya or Malaysian a decade from now.

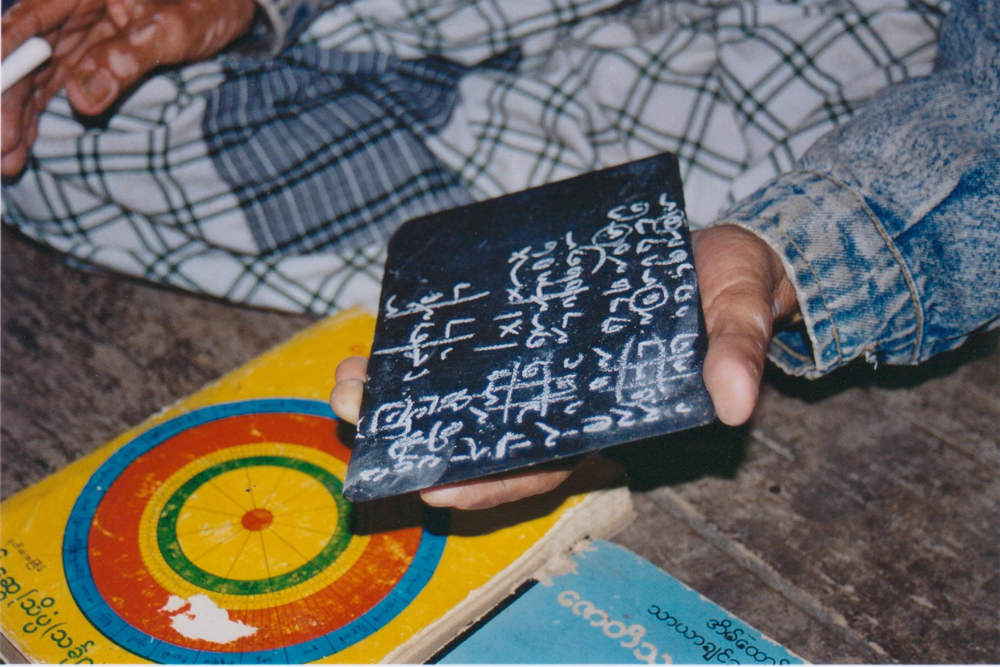

Iftar dinner with the Rohingya in Kuala Lumpur. Photo courtesy of the author.

Iftar dinner with the Rohingya in Kuala Lumpur. Photo courtesy of the author.

Conversations in these closed gatherings are rarely two-person affairs, and soon other Rohingya in attendance weighed in with their views as the meal progressed. Some believed that the next generation would remain uncompromisingly Rohingya, while others felt that their identities would inevitably become mixed over time. Conversations of this kind are apparently nothing new; they have been circulating in the Rohingya community in Malaysia for a while. However, this evening's chat made clear that an identity crisis to which there are no clear answers has now emerged—the majority of approximately three to four million Rohingya now live as a diaspora in foreign lands, scattered across Saudi Arabia, South Asia and Southeast Asia, far away from their ancestral homeland in Myanmar. This region-wide multigenerational identity crisis is the focus of this article.

At the heart of this crisis is the enduring statelessness of the Rohingya, which stems from their historic marginalisation and persecution in Myanmar by the military junta, the stripping of their citizenship, and their forced expulsion from the country. The probability of a repatriation is slim, even for those recently expelled in the aftermath of the military’s genocide attacks in 2017. This limbo of statelessness is now multigenerational and constitutes an inherited crisis. While the Rohingya are known as the largest stateless population in the world, it is important to note that two overlapping conceptions of statelessness actually apply to them. The first refers to stateless persons, while the second refers to stateless people. The difference is not semantical but categorical.

The term “stateless persons” provides a more classical understanding of statelessness in the legal sense. This is the statelessness that is defined in the 1954 UN Convention Relating to the Status of Stateless Persons, with respect to individuals lacking a nationality, and by extension, citizenship. The plight of those suffering from this kind of statelessness has been eloquently expounded by historian Hannah Arendt, who used the example of Jews who lacked access to basic human rights in the interwar period, such as legal protections or social services, by virtue of not having a state of their own.

This category of statelessness manifests itself in two forms. Those who are de jure stateless may have been dispossessed of citizenship and lack a state authority that can provide them that formal status, such as in the case of the Rohingya still remaining in Myanmar or the majority of Rohingya refugees outside the country. On the other hand, the de facto stateless may have a legal claim to citizenship but are denied avenues to claim it or face practical hurdles in receiving rights of citizenship. This applies largely to the Rohingya communities who settled in Pakistan before the separation of East and West Pakistan in 1971, where a large part of the community is now facing difficulty acquiring Pakistani nationality due to absence of documents proving their roots in the land.

Secondly, and perhaps lesser noted, the Rohingya category of statelessness is a socio-political one, where those affected are members of a “stateless nation” or a stateless people. Ethnic groups with a historical presence in a land of origin that are effectively denied independence or self-autonomy there or have been cast out and cannot return, fall under this category. Classic cases of such groups include the Roma, the Palestinians, and the Kurds. Research on Palestinian and Kurdish people has shown that such a form of statelessness manifests in feelings of dislocation and lack of belonging, even for those who manage to resettle in stable host states and gain citizenship. For the Rohingya, there is still much to be explored regarding how being a “stateless people” affects their collective and individual sense of identity, with implications for researchers on their ethno-cultural evolution and for policymakers seeking to integrate them in their countries.

As mentioned, the adoption of language by a younger generation of Rohingya in their host state can be framed as a traditional dilemma faced by many second-generation diaspora groups in negotiating and adopting local practices while retaining their core ethnic identity. This phenomenon of cultural loss witnessed primarily through loss of language is not exclusive to the Rohingya; the same is experienced by other indigenous refugees and diaspora groups across the South Asian and Southeast Asian region in their second and third generations settled in a host country, such as the Tamil diaspora.

The Rohingya fall into a category of statelessness, where they are effectively denied independence or self-autonomy. Credits: Mohammed Zonaid8, Shutterstock.

The Rohingya fall into a category of statelessness, where they are effectively denied independence or self-autonomy. Credits: Mohammed Zonaid8, Shutterstock.

However, in addition to statelessness, the Rohingya face a genocidal assault on their collective identity. Therefore, there is a deeper existential incentive for the community to ensure that aspects of their culture are retained, perhaps even at the cost of integration into the host societies. This desire to protect the community against threats of assimilation may be felt more keenly by those Rohingya who have access to education and subscribe to a communal narrative that traces their cultural heritage and practices back to their homeland of Arakan. From my own interactions with these refugee Rohingya communities, even if they lack a level of awareness of their own communal narrative, they still report an enduring sense of dislocation of being cast adrift from their land of origin and robbed of a point of reference, generating a sense of isolation in communities where they have settled. Anis, a 32-year-old Rohingya activist based in Penang, describes this notion as being “invisible” in a world of distinct forms of state-based legitimacy and firm notions of home. Other Rohingya activists have resisted the use of the term “stateless” as it implies disempowerment for the Rohingya in their struggle to reclaim citizenship in their homeland. Community members often find themselves stuck between the proverbial rock and hard place, the former being physical disconnection from Arakan which as the years and decades pass becomes more distant in communal memory as they contend with the harsh realities of survival away from home. The latter refers to the barriers to inclusion, legal and socially enforced, that they experience in host societies. Return becomes increasingly impossible yet the society in which they live does not accept them. What remains may be a sense that there is no place for them in the world to set their roots. This, I argue, may perpetuate forms of self-exclusionary behaviour and add to the intergenerational trauma they experience.

Policy advocates calling for the end to legal statelessness often frame the affordance of citizenship as a panacea, as a means to rectify the sense of exclusion felt by such populations. Yet it is the second category of statelessness which suggests that even affording the Rohingya access to legal documented status and citizenship, which may certainly address certain matters of basic rights to services, may still leave them experiencing a communal sense of exclusion. This is because the heart of the Rohingya dilemma is not purely a legal issue but one that is deeply connected to perceived threats to their wider identity as a people. It is certainly possible then for stateless people to still find themselves at the margins of host societies even if documentation and status issues are settled.

As the prospect of return for the Rohingya appears unlikely and they continue to remain living in their sequestered communities in host countries, the question of how this identity crisis will evolve remains, and whether they can find the means to persevere. According to Muhammad Noor, chair of the Rohingya Language Council, “Preservation of language and culture is vital for the Rohingya people to protect our identity, even though we are living away from Arakan. The challenge for us is to be able to contribute and be part of societies where we have settled while also keeping a strong connection to being a Rohingya. It is not easy." The longer they remain in their host societies, the more compelling it becomes for policymakers of those societies to find a durable solution for integrating them into productive members of their society rather than becoming prey to the informal economy.

Identity may be the Rohingya's defining issue in years to come. Credits: Gaie Uchel, Shutterstock.

Identity may be the Rohingya's defining issue in years to come. Credits: Gaie Uchel, Shutterstock.

From the perspective of a researcher, what I find fascinating is the centrality of identity to the Rohingya and the trade-offs made to retain or hide such an identity in their condition of undocumented limbo seeking to build dignified lives for themselves wherever they are based. There are three dimensions to the lingering multigenerational issue of Rohingya diaspora communities that feed into my own research moving forward. The first is how Rohingya community members negotiate their own personal identity with the country they reside in with the self-understood notion of “Rohingya-ness”, and whether there is a perceived conflict in balancing these two. The second is whether Rohingya self-exclusion, which can be observed to different degrees in many Rohingya communities including those settled in the West, is inevitably linked to particular dynamics in those communities and their documentation status or whether their membership in a wider transnational stateless group has a larger role to play in this. The last dimension is how policymakers can effectively incorporate particularities of the Rohingya, including types of isolationist behaviour, into their programmes for integration in the future that can ensure a better degree of success without pushing such communities further into the margins in which they have lived for decades.

As I think back of my Rohingya friends and colleagues, I do also note that there now exist prevailing and heated debates within the community as to what are the boundaries and traditions tied to the Rohingya culture. This is especially so given the differences arising within communities in different geographical contexts, and whether a single monolithic notion of “Rohingya” is really defensible. Even as their humanitarian disaster continues to unfold, this may be their defining struggle in the years to come.

The views expressed in this forum are those of the individual authors and do not represent the views of the Asia Research Institute, National University of Singapore, or the institutions to which the authors are attached.

Sheikh Saqib Muneer is currently a PhD researcher at the S. Rajaratnam School of International Studies (RSIS), Singapore, researching Rohingya identity, statelessness and assimilation strategies. Saqib's work centres on advocacy, social inclusion and educational access for refugees and stateless people. He serves as Project Director for the Rohingya Project, a grassroots initiative for the empowerment of the Rohingya diaspora using blockchain technology. He is also a co-founder and advisor for the Refugee Coalition of Malaysia (RCOM) where he focuses on creating formal pathways for refugee placement in higher education institutes in Malaysia.