In Conversation with Dr Céline Coderey

On December 31, 2024, another era came to a close with Dr Céline Coderey departing ARI after eleven years! Céline first joined ARI in January 2014 as a Postdoctoral Fellow in the STS Cluster where she was working on a research project about the medical system in contemporary Myanmar. She became a Research Fellow in 2016 and shifted to the IAE Cluster in 2023 with a new project on dance and cultural revendication in the Marquesas Islands (French Polynesia).

For the entire duration of her appointment with ARI, Céline was also working as Lecturer in Tembusu College, and, for one semester in 2020, was appointed as joint-Lecturer to Yale-NUS College. There, she taught the courses Biomedicine and Singapore Society, Time and Life, SKIN, and Medical Anthropology.

Her book, The Power of Remainder: Politics and Poetics of Healing in Buddhist Myanmar, will be published in 2025 by the University of Hawaiʻi Press. From February 2025, Céline will be Research Scholar at the University of Hawaiʻi at Mānoa.

Firstly, we’re sorry to see you go, but excited for your future endeavours! How has your time been at ARI?

ARI is the best working place I have ever experienced. It is the ideal institute for a postdoctoral fellow who needs to expand and consolidate one’s academic status. ARI indeed provides researchers with the time, financial and logistic support, and intellectual stimuli one needs in order to deepen one’s research, explore new paths, conduct fieldwork, network, organise and participate in conferences and workshops, and publish.

The intellectual vibrancy at ARI, channelled through the different clusters’ and institution’s activities is exceptionally stimulating, all the more so since the institute always welcomes researchers from different nationalities, disciplinary background and research topics. Thanks to this ever-changing human landscape I had the extraordinary opportunity to build some of the most important and dearest friendships I have in my life. Tabea Bork-Hüffer, Giuseppe Bolotta, Carola Lorea, Catherine Scheer, Bernando Brown, Karen Mc Namara, Catherine Smith, Michiel Baas, Malini Sur, Michael Feener, Tim Winter and Aparna Nambiar are persons I have shared and continue to share fragments of intellectual and personal life I would not trade for anything.

Friendships grown in ARI in the midst of discussing papers, joining conferences, eating spicy mala, enjoying riverside walks, and sharing laughters, survive any time and space gap.

How has living in Singapore for over a decade impacted your research interests, and life?

Being so close to Myanmar allowed me to travel there for fieldwork regularly (at least till the military coup in 2021) and to follow quite closely the rapid change the country has gone through since 2014 when I joined ARI. Singapore being based in the heart of Asia, it greatly facilitated conference participation around the region and hence academic networking and exchange.

My personal curiosity to discover Asia brought me to travel all around every time I had the chance to do so. The cultural diversity of Asia is, at least in part, reproduced also in Singapore, and this variety is one of the aspects of the city I have appreciated the most during my time there. Singapore is modern and dynamic, but also provides a sense of coziness and familiarity which has been for me a source of comfort and security. At least till I felt the need to move beyond it.

Who are some of the most important intellectual influences you've had during your time at ARI?

Certainly Maitrii Aung Thwin, Michael Feener and Tim Winter. Maitrii Aung-Thwin, ARI Deputy Director, has a unique contagious positive energy and sparkling enthusiasm that always helped me feel reassured and motivated about my research on Myanmar. His extended knowledge about Myanmar complemented by a strong inter-regional approach, allowed me to see the broader relevance of my own research. Michael Feener, previous leader of the Religion and Globalisation Cluster invited me to partake in the reading groups of his cluster, and graciously offered to read part of my (at that time still in progress) book and provided me with hints that have been crucial to the conceptual reframing of my work. With his extraordinary intellectual agility and genuine care for people’s academic growth, Tim Winter, IAE cluster leader, has been fundamental in helping me strengthen the coherence and shape of my current research project.

Your new book, The Power of Remainder: Politics and Poetics of Healing in Myanmar will be published in 2025. What’s it about?

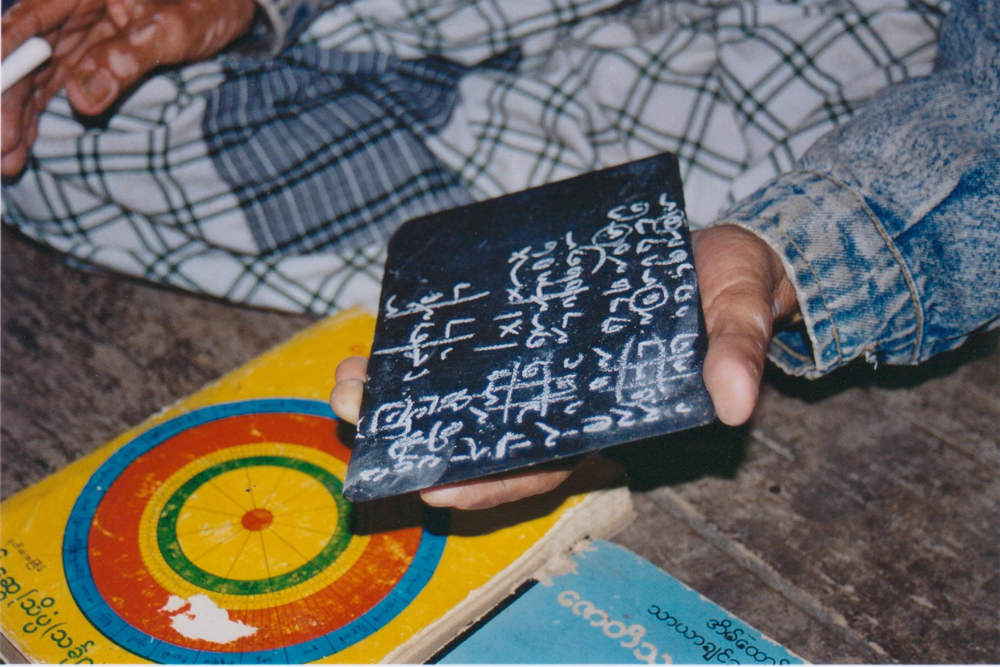

Focusing on the Buddhist communities of Rakhine, a geopolitically peripheral state, The Power of Remainder is the first study to explore their rich and diverse “medical repertoire.” From divination and Buddhist prayers to herbal and alchemic medicines, biomedical care, and astrological offerings, this repertoire reflects an intricate interplay of biological, social, cosmological, and political forces. Drawing on 30 months of fieldwork conducted between 2004 and 2019, this study reveals how plurality, positionality, and efficacy are interconnected. The necessity for diverse healing approaches is driven not only by the desire to live and be well but also by the categorisations and hierarchies imposed on medical practices, knowledge, and people.

These categorisations—shaped by governance and nation-building—affect how healers deploy resources and how users access them, ultimately influencing their effectiveness. At the heart of this work lies the innovative concept of "remainder”, which reimagines healing as a process of navigating what is left behind, left out, or left unresolved. Remainders encompass karmic residues from past lives that determine vulnerability to illness, the nature of disorders, and room for manoeuvre one has to cure them, but also the marginal positions of people and practices within the social space, symptoms lingering in one’s body, and the medical gaps encountered in the healing journey.

Far from being merely constraining, these remainders offer a creative space for resilience, adaptability, and hope. This duality—where marginalisation gives rise to innovation—positions The Power of Remainder as a bold challenge to conventional understandings of healing.

You dedicated 16 years to the study of medical pluralism in Myanmar and neighbouring Southeast Asian countries. What drew you to studying medical anthropology of Myanmar and Southeast Asia?

In my anthropological studies, I have always been deeply fascinated by bodily rituals, religious beliefs and anything that felt hard to explain from a Cartesian perspective. Reading a book from the late Italian writer and journalist Tiziano Terzani that touched upon the topic of divination in Asia further oriented my interest toward practices meant to deal with uncertainty and suffering. My original plan when I started my masters was to do research on Papua New Guinea but I have been precluded that path for safety reasons and reoriented toward Asia.

François Robinne, the supervisor I was allocated, is a specialist of Myanmar and in conversation with him I felt deeply intrigued by this country and decided to “give it a try”. A choice I have never regretted. The cultural complexity, the generosity of people, the natural makeup, and the violent political landscape of this country have provided me with the most enriching human experience I have ever had. I thrived to unpack the pluralistic journeys of health seeking amidst heterogeneous medical repertoires, desire to live, and geo-political marginalisation. The expansion of my study to the broader SEA region, and notably other Theravadin countries, came naturally from the desire to understand similarities and differences. Since structural violence and social suffering became more and more prevalent with time in my region of study, notably toward the Rohingya communities, I soon had the need to expand my focus to the suffering experienced by displaced communities, and started to work on questions of temporalities, memory and resilience.

In parallel I have started providing psychosocial support training to local community-based organisations working for social harmony in Rakhine State.

Your current research centres on Polynesia and dance. Does this mark a substantial departure from your previous focus on medical anthropology, or are there connections between the two areas of interest?

I think that there is always a fil rouge which is the interest for communities that have undergone some forms of marginalisation and political violence, in the case of Rakhine it is related to the oppressive but also neglective politics of the Burman military regime that have put Rakhine people in a vulnerable condition, while for the Marquesas islands it has been by the hands of the colonisers and missionaries that have led to drastic demographic and cultural loss.

Moreover, with both healing practices or dance it is about creative ways to master one’s destiny, that of the individual and of the community. For me it is always about resilience, about ways of coping with uncertainty and social injustice and to valorise cultural heritage.

Although my research focus has shifted, I still have so much material from my research on Myanmar that I want to publish and regularly receive invitations to join conferences and publication projects. I also keep active in my humanitarian work for Myanmar. So, yes, the country is going to stay with me for much longer.

The views expressed in this forum are those of the individual authors and do not represent the views of the Asia Research Institute, National University of Singapore, or the institutions to which the authors are attached.

Dr Céline Coderey received her M.A and PhD in Anthropology from the University of Provence, Aix-Marseille 1 (France) and her M.A. in Psychology from the University of Lausanne (Switzerland). She also holds a Diploma in Burmese Language from the National Institute of Oriental Language and Civilization in Paris.