In Conversation with Dr Fathun Karib

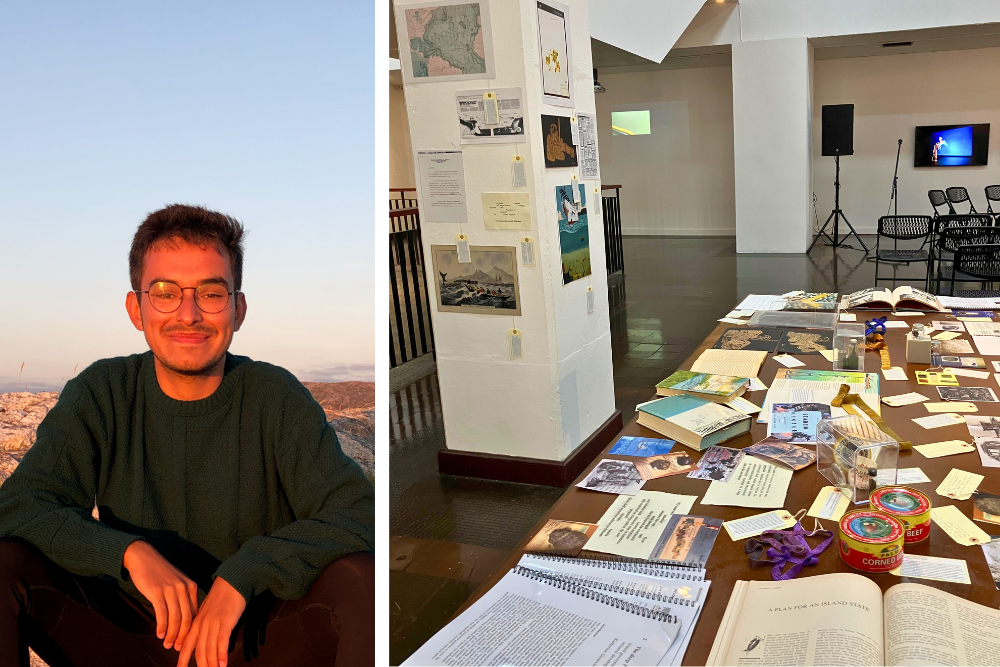

Junior high school friends, 1997.

Junior high school friends, 1997.

Can you describe the place where you grew up and how that environment influenced your perspective or experiences?

I grew up in the southern part of Jakarta, near an area known as Blok M, which is about 1.3 to 2 kilometers from my neighborhood. Blok M has been around since 1968, and when my family moved closer to it in 1982, it became a mix of a modern mall and a traditional market, similar to the Clementi Mall complex during the 1990s. I enjoyed going there with my cousin to play “dingdong” or arcade video games that required coins in a place called Melawai.

One important moment in my life occurred during my teenage years and the end of Suharto’s New Order regime. Politics dominated family conversations, and I was disinterested in school subjects during primary and junior high school. However, I now realise I was learning fascinating stories and knowledge from my immediate environment. During the 8th grade, I started to hang out with older friends involved in the punk and hardcore scenes, typically 4 to 10 years older than me. They were against the Suharto regime, and I felt like I had found a second home among them. Outside my family’s house, I discovered a community of college students passionate about punk rock, hardcore music, politics, history, and resistance discussions. These older punk and hardcore friends are known as the Locos Crew.

From 1996 to 1998, we would gather on Blok M Street every Saturday night in front of Il Primo. This shoe store transformed into a street food venue offering what we called “Gudeg Lesehan” after 9 pm. Gudeg is a traditional Javanese dish, and lesehan means eating in the street with mats without chairs or tables. I would attend punk and hardcore gigs on Saturday afternoons and meet them. They eventually invited me to join them at Lesehan, where we often stayed until 6 or 7 AM on Sunday mornings. There were no buses after midnight despite the bus terminal being nearby. I would walk home afterward since my house was relatively close to theirs. After catching up on sleep on Sunday afternoons, I returned to the gigs, as we typically had gigs on Friday, Saturday, and Sunday nights. I just realized why my parents allowed me to do this; I don’t know the reason. I have kids and definitely will not allow them to do what I’ve done in the past, hehehe.

I often asked them numerous questions. I learned much about politics and social reality from the punk and hardcore scenes through punk zines, lyrics, and music. My college friends would answer me by referencing scholars, intellectuals, or relevant books. Through these interactions, I gained critical thinking skills, heavily influenced by critical intellectuals. School, especially junior high, felt uninteresting to me. Still, I found that I was learning a great deal from the streets and my older acquaintances in the punk scene.

My experience in the punk scene and living in the twilight of the New Order shaped my perspective on social justice before entering university as an undergraduate. I learned that punk music emerged as a response to authoritarian regimes and as a form of youth expression in politics through cultural statements. My experiences on the streets and interactions with friends in the punk, hardcore, and skinhead scenes, which spanned various class backgrounds, many of whom were from lower socioeconomic statuses, profoundly changed how I think.

What led you into teaching and research and why did you choose sociology as a discipline?

I remember that during primary school, I always wanted to be a teacher, but I didn’t enjoy going to school. After reading an introductory book in high school, I decided that I wanted to be a sociologist. Looking back, I realise I achieved these two dreams, becoming a teacher and sociologist, that seemed impossible when I was on the street. I recall a song by the Sex Pistols that proclaimed, "God Save the Queen," and had lyrics that said, "No Future." However, it turns out that punk can indeed have a future.

What led me to teach and conduct research is that I am quite similar to “Curious George,” the monkey from a U.S. TV series. While pursuing my Ph.D. in Binghamton, United States, I would watch Curious George with my three-year-old daughter. It struck me then, after almost thirty years, that I have been filled with curiosity all my life, just like George.

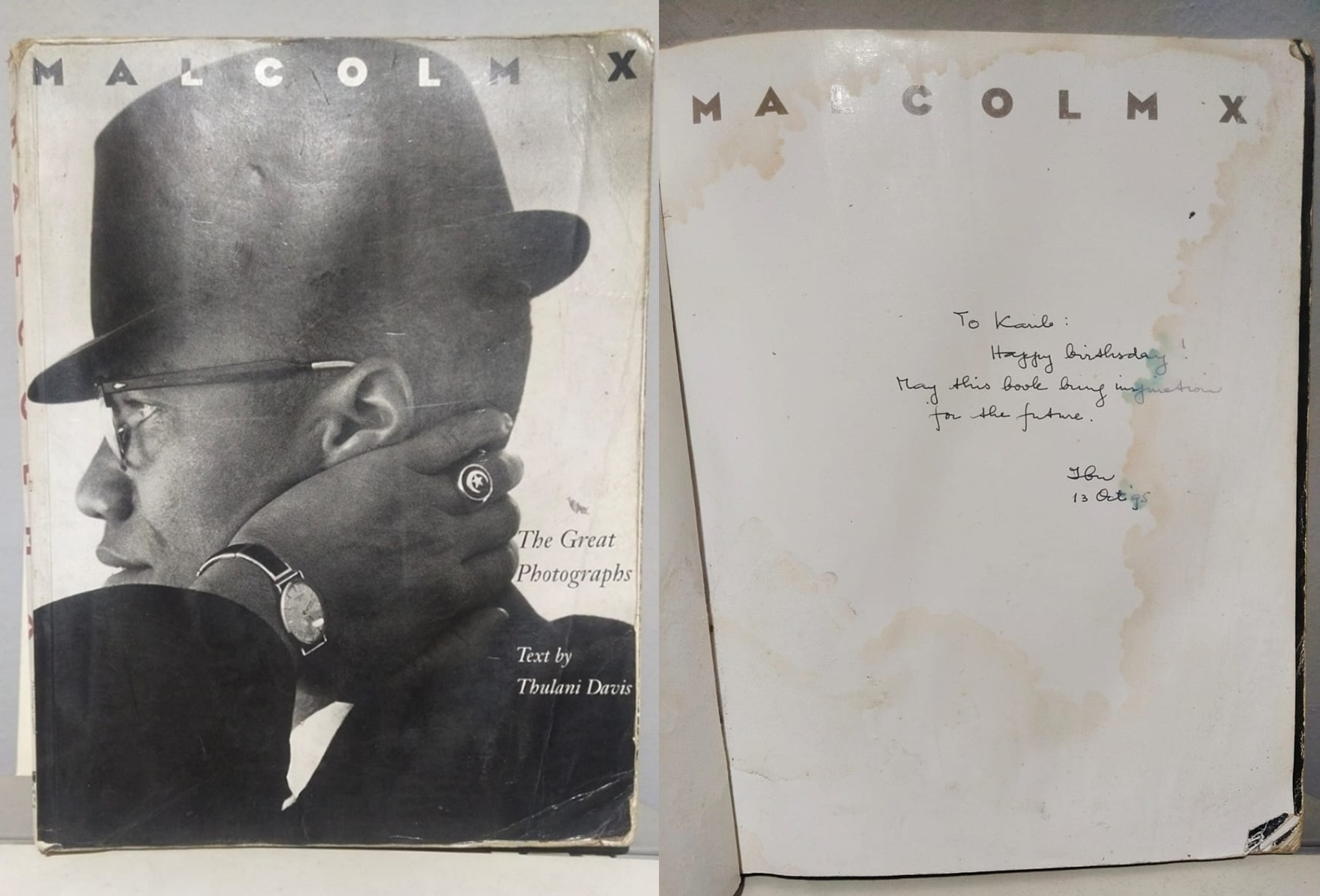

I never asked myself what drives and shapes my curiosity. In my family, my parents never treated me as a child younger than them. They frequently discussed fascinating topics, especially history and politics. I guess they were the first people to teach me social and political issues. When I was in sixth grade, I began reading about Malcolm X and my mom bought me an engaging birthday book on the subject. She worked in a publishing company and had the opportunity to travel to book fairs. She bought me many books and took me along to these events in Jakarta, telling me she would only purchase something for me if it was a book. She encouraged me to take anything I wanted, as long as it was a book. During my time when I was teenager, I often volunteered in her book booth.

My experience in the punk scene began in junior high school and sparked my interest in reading critical literature. I wanted to learn more and discovered that sociology offered fascinating insights. I remember purchasing a book titled “Mengenal Sosiologi; For Beginners,” a translated version of "Sociology for Beginners" by Richard Osborn and Borin Van Loon. It was a great introductory book filled with graphics, cartoons, and illustrations. I informed my parents that I wanted to attend college. Although I was supposed to start university in 2000, I failed the 10th grade during my punk years from 1996 to 2000 and didn’t advance to 11th grade. I spent time with punk and hardcore friends around Jakarta, from Manggarai and Ciledug to Blok A, Ciganjur, and Kuningan instead of going to school. Eventually, it also made me want to learn more and I decided to return to school.

In 2001, I enrolled in a university, pursuing international relations while simultaneously applying to the sociology program at the University of Indonesia. Once I was accepted into UI, I dropped out of the international relations program. I fell in love with sociology because it explores human relationships in nearly every context, connecting to various disciplines. During my undergraduate studies, I even learned Barthesian semiotics from the humanities. While I criticised positivist social science, I found connections with fields such as anthropology, history, international relations, geography, and geology through sociology. I consider myself a critical historical social scientist rather than just a sociologist, perhaps a historical sociologist.

My main motivation aligns with my punk roots, focusing on social justice issues. Sociology helps explain structural inequalities and other phenomena that fuel my curiosity.

As well as an academic, you’re also a musician and have even written a thesis on the History of the Jakarta Punk Community. How do you juggle the worlds of academia and music, both of which can be pretty all-consuming?

We started a band between 1996 and 1997 during our junior high school final year. Our first band name was “No Body is a Hero,” but it didn’t resonate with us. After a friend suggested a new name, we became Cryptical Death. We began playing at various punk and hardcore gigs. In 1997, as we transitioned from junior high to high school, we were fortunate to participate in a hardcore punk compilation called Walk Together, Rock Together made by the Locos Crew, alongside senior hardcore punk bands such as Antispetic, Dirty Edge and Straight Answer.

We started a band between 1996 and 1997 during our junior high school final year. Our first band name was “No Body is a Hero,” but it didn’t resonate with us. After a friend suggested a new name, we became Cryptical Death. We began playing at various punk and hardcore gigs. In 1997, as we transitioned from junior high to high school, we were fortunate to participate in a hardcore punk compilation called Walk Together, Rock Together made by the Locos Crew, alongside senior hardcore punk bands such as Antispetic, Dirty Edge and Straight Answer.

Karib's first band No Body is a Hero, 1997-2000. The group later changed its name to Cryptical Death.

From 1998 to 2000, in 10th and 11th grade, I co-produced a DIY (Do It Yourself) independent record with my friend Iyos under Movement Records. Our first release was a punk compilation album titled “Still One, Still Proud,” featuring 13 punk and skinhead bands from Jakarta, including Cryptical Death.

At that time, my priorities were different. Punk was my main focus, and the movement mattered more to me than my education. I considered school merely a hobby to impress my parents, which resulted in my failure in 10th grade because my grades were mostly in the E and F range. In 2000, we released our first album, “Fight, Survive, Existence.” I was lucky to be accepted into the Sociology department at the University of Indonesia, which changed everything for me. During my senior year, I served as a teaching assistant for courses like Introduction to Sociology and the Indonesian Social System. My interest shifted more towards studying sociology rather than hanging out.

There was a band named Descendent, whose vocalist, Milo, chose to go to college, and I found myself following in his footsteps. There were moments when the band went on hiatus as I focused on my studies. Our second album was finally released in 2009, after around an eight-year gap due to my concentration on sociology. From 2010 to 2019, I pursued a master’s degree in Germany and a Ph.D. in the United States. The band remained on hiatus for an extended period.

During the COVID pandemic, while I was finishing my dissertation research and could not return to the United States, I reconnected with Farid, my close friend and our guitarist. We began hanging out again and discussing various socio-political topics, which led us to create new songs. We released a single in 2020-2021. After completing my dissertation from mid-2021 to mid-2022 and successfully defending it, I returned to Jakarta. We made our comeback with a new band formation consisting of just Farid and me, the last two members since 1997 and new members Epik, Toan and komar. We recorded our third album, “Pralaya Semesta,” from October to November 2023 and released it on 14 February, 2025. We chose this date to coincide with the Indonesian Presidential Election. A few months earlier, we released our single “Zaman Kegelapan” (The Dark Age), anticipating a dark future for Indonesian democracy after the presidential election.

On stage and two singles 'Pandemik Semesta' (Pandemic Universe) and 'Zaman Kegelapan' (The Dark Age).

The reason I can commit to this long-term project is that Farid understands my situation; our friendship strengthens our bond. Even after being away for long periods, when we reunite, it feels like we’re back in junior high school. Some things never change with your close friends. He knows exactly what I want in terms of music. I often discuss political and social issues with him, saying, “Look, our next album is going to be dark because we are in the midst of a crisis.” We talked about various topics, and he translated those discussions into guitar compositions. He knows precisely how to develop songs that align with my lyrics. While Farid and the other band members work as professionals in their own fields, we all share the same ideas and humor.

I believe this is why we make music; it’s a way to maintain our sanity in this chaotic world. I need that sense of sanity.

What drew you to pursue a Postdoc at ARI?

Curiosity like George. I want to have someone to talk to and discuss ideas. I was in Jakarta after my Ph.D. I am in the transition and transformation period and need some space to rethink and reflect on my intellectual journey. On the other hand, it is like during my teenage years; I want to meet a lot of people, see, listen, and discuss a lot of things. I never considered going to ARI for a job and working in higher learning or research institutions. I wanted to have a playground where I could share ideas and think together.

I have always been accustomed to engaging in conversations on various topics during my childhood and adolescence. As an undergraduate, master's, and PhD student, I sought out individuals who were happy and open to chatting. I often interacted with people 20 to 30 years older than me, and they were willing to share their thoughts and ideas. I now realise that this inclination to connect has been present since childhood or adolescence when I would engage in discussions and ask questions with my older friends in the punk scene.

For me, it's not just about the postdoc, the job, or the project; it's primarily about having a companion with whom I can think and explore ideas together. Two of my dissertation supervisors are in their 70s and have shared their deepest concerns and feelings about the world with me. When I came to them, they became my playground. I can do anything, think anything, and experiment with anything. All I wanted was to find a playground like when you meet your friends in the school playground, and you or your friends bring new toys or other new stuff. When I went to ARI, I had similar feelings and attitudes. I believe I have found that same connection at ARI as well, as a playground. I can do things best if I consider going to the playground.

While at ARI you’ll be developing part of your dissertation, Living in the Ruins of the Capitalocene into a book manuscript. Could you tell us more about the concept of the Capitalocene?

The Capitalocene is an alternative concept of the Anthropocene that marks the period of humans as geological forces shaping the earth. I was at Binghamton for seven years, learning about environmental history and global capitalism. During those years, I read and learned about the current debate in Academia, and the debate of the Anthropocene and Capitalocene is one of them. The concept assumes that current capitalist behaviors drive and produce environmental crises, not humans, in general and abstract terms. Some humans have more capacity and ability than others, so it is impossible to say that all humans generate environmental crises. Capitalocene emphasises the dimension of power, that certain human conditions, whether economic, political, social, or environmental, should be seen as part of social relations, as relations. In my case, the mudflow disaster triggered by natural gas drilling activities is the key factor that drove the environmental crisis in Porong, Sidoarjo. I tried to highlight the disaster as a geological event and phenomenon and how power relations between the corporations, states, and affected villagers appear and can be understood.

After my doctoral period, I want to move and depart from the debate and try to find a different way to look at human-nature relationships. One of the difficulties in rewriting the dissertation into a book is that I wanted the manuscript to move from the debate of Anthropocene and Capitalocene. I am working on focusing on geological dimensions and experimenting to see whether there is a possibility of developing a new vocabulary or a new concept that detaches from my previous intellectual perspective. I think I made some progress in the sense that I began to create my own concept regarding geology. Still, it is from my new geology and empire project, not the dissertation.

I need more time to read, mainly because I want to develop concepts and make coherent arguments from one chapter to another. Each chapter in the dissertation consists of concepts but making it coherent is challenging. One thing I am missing now is that I feel alone. The project is too specific, and maybe you don’t have someone to talk to.

What do you like to do during your downtime in Singapore?

I feel fortunate to live in the Pandan Reservoir area. As it is a vast water reservoir, I often take long walks that last 1.5 to 2 hours. If lucky, I might spot a family of otters in the morning. These otters enjoy swimming, and I learned that they travel from a nearby HDB by using the water infrastructure to access the reservoir.

I also frequently see biawaks, or large lizards, swimming in the water. Sometimes, they stare at me as if to say, "Why are you in my backyard?" When I lived in Jakarta, I was near a river (Sungai), and the biawaks would often come onto our rooftops.

In addition to my walks, I often visit the swimming pool on campus. However, something I missed during my first year in Singapore was spending time at the library. I used to love browsing through bookshelves and could easily stay on campus until midnight. I've heard that the ISEAS library is interesting, but I haven't visited it yet for some reason.

The views expressed in this forum are those of the individual authors and do not represent the views of the Asia Research Institute, National University of Singapore, or the institutions to which the authors are attached.

Dr Fathun Karib is a joint appointment postdoctoral fellow under the ARI-DIJ Research Partnership on Asian Infrastructures and affiliated to the Inter-Asia Engagements and Science, Technology, and Society clusters at Asia Research Institute, National University of Singapore.

Dr Karib previously worked as a sociology lecturer at the Department of Sociology, UIN Syarif Hidayatullah Jakarta. He holds a PhD in Sociology from the State University of New York at Binghamton. His current research interests are energy and environmental history, critical agrarian studies, Anthropocene/Capitalocene, political economy of disaster, commodity frontiers, and the history of geology as a science.