Viral Humour and Violent Borders: Memes as Cultural Weapons in the Kashmir Conflict

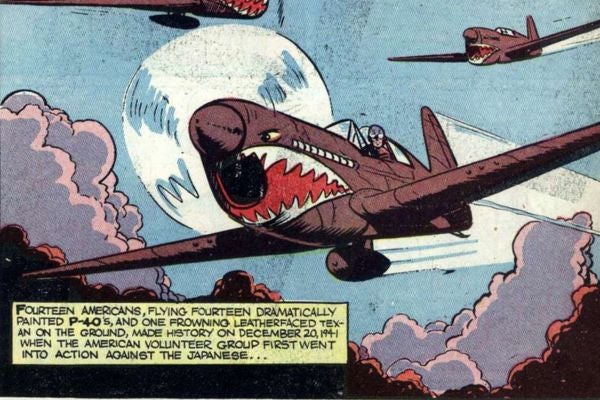

Illustration generated by ChatGPT using OpenAI’s DALL·E model (2025)

In recent months, memes from China targeting the American President Donald Trump and his trade tariffs have flooded the internet. These memes are often laced with themes of China’s manufacturing strength, technological prowess and national resilience - portraying China as stoic and rational in contrast to a chaotic and declining U.S. This piece takes up such themes but turns to the ‘diss track’ meme video released on Chinese social media amid escalating tensions between India and Pakistan. The video has since gone viral across local, regional and global social media platforms. The full lyrics of the song are not readily available online, the video includes Mandarin and English subtitles, that offer insight into its narrative and tone. The following excerpt presents the subtitles as they appear in the video:

Indian Rafale

刚买的飞机 I just bought a plane (x 6)

被打啦 Got beaten up (x 6)

丢人呐 What a shame

飞机都被打掉啦 the planes were all destroyed

一架都没回家 Not a single one has returned home

九十亿全部白花 Nine billion all white flowers

破飞机 Broken airplane

还没出国就散架 fell apart before going abroad

雷达都是坏哒 the radar is all broken

什么都看不见呀 I can’t see anything

气死啦 I am so angry

网上到处都在发 It’s being posted everywhere online

他们笑掉大牙 They laughed their teeth off

这次丢人丢大啦 It’s embarrassing this time

换飞机 Changing planes

回家全部换新的 Go home and replace everything with new ones

就买他们款的 Just buy the same model as theirs

比他们多买十架 Buy ten more than them

他们不会卖哒 They won’t sell it

刚买的飞机 I just bought a plane

被打啦 Got beaten up

他们的飞机 Their plane

太刁了 It’s too awesome

Amid near war-like tensions, misinformation and disinformation circulated widely online. Several unverified claims on social media alleged that multiple Indian aircrafts were shot down. In no time, the fake news and claims questioning the effectiveness of the Rafale aircraft became a subject of ridicule, particularly when compared to the Chinese fighter jets used by Pakistan. In this context, Chinese influencers released a satirical video on Douyin, mocking India’s perceived military failure. Set to Indian Punjabi artist Daler Mehndi’s “Tunak Tunak Tun” song, the parody shows four Chinese men in darkened face with turbans, moustaches, beards, tilaks, and toy planes on their heads, mimicking Indian cultural symbols. Sung in Mandarin with English subtitles, the lyrics mock India’s damaged aircraft and national embarrassment, while praising the China-made jets used by Pakistan. The chorus “just bought a plane, got shot down – da da da” reinforces India’s supposed loss of face both diplomatically and militarily.

According to South China Morning Post, the video was released by Chinese influencer “Brother Hao” Hao Gege (豪哥哥) and has been widely celebrated by Chinese netizens for showcasing the success of Chinese fighter jets in the India-Pakistan conflict. Hailed as a “DeepSeek” moment for China’s defence industry, the video - titled Indian Rafale - quickly went viral across platforms like Weibo, TikTok, YouTube, X, and Instagram. The release of the video during a live conflict is a textbook example of memetic warfare. Its swift production during a live geopolitical conflict highlights how entertainment and social media are weaponised as tools of hybrid warfare. Juxtaposing music, sarcasm, and parody, the video ridicules India’s military strength in an engaging format that amplifies emotional impact while lowering cognitive barriers. The underlying intent is not factual critique but public humiliation under the guise of humour and internet savvy; a classic tactic of psychological warfare. The timing and tone of the meme position China as a silent yet powerful supporter of Pakistan in the conflict.

The stock value of these specific Chinese aircraft used during the combat have jumped, gaining more attention from Western observers. The western media is now closely observing the usage of China-made aircrafts and their performance in this conflict. By referring to China-made aircraft and contrasting them with India’s Western imports, the video now functions as soft propaganda for Chinese military exports, subtly asserting the superiority of Chinese technology. The diss track format, a popular genre in online clout culture, draws heavily from meme culture, characterised by repetition, exaggeration, viral hooks, and an intentional combination of low production value paired with high emotional impact. In their works on memes and digital culture, Milner and Shifman identify these features as hallmarks of affective internet vernaculars. It compresses a complex geopolitical episode into a meme-able narrative, wherein India is outdated and incompetent and Pakistan backed by China is technologically superior. The objective is not to convey military truth, but to shape perception through virality. This reinforces polarised geopolitical identities: “us” (Pakistan/China) versus “them” (India).

Weaponised humour and nationalist sentiment serve to deepen in-group solidarity while delegitimising the opponent; a strategy that is well discussed by Michael Billig and others. They also represent a form of banal militarism, akin to Billig’s banal nationalism. In critical media and heritage studies, such memes can be theorised as postmodern artefacts of digital conflict. Importantly, the video taps into deeper colonial legacies, something which Chinese netizens and Western viewers may simply miss. It deploys a memetic form of racialised mockery through visual signifiers such as the turban, brown face, and hyperbolic Indian stereotypes.

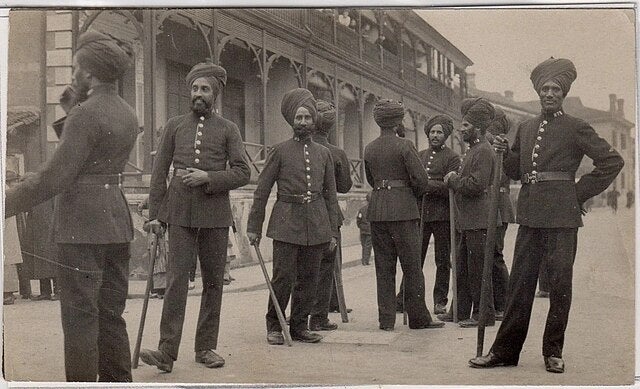

The exaggerated depiction of turbans, tied in a manner resembling those worn by Indian Sikhs, resurrects colonial scripts embedded in the term asan (阿三), a racialised and derogatory Chinese expression rooted in the historical presence of Sikh soldiers in colonial Shanghai. The mockery of Indian aircraft, combined with these caricatured representations of Sikh identity invokes the colonial and racialised legacies embedded in asan, enabling a critical reading of how Chinese discourses visually and discursively frame Indians and Indian-ness.

Sikh policemen at the time of the December 1905 Shanghai Mixed Court riots. Source: Wikimedia Commons.

Mockery with a Memory: The Colonial Aftertaste of Digital Nationalism

Thirteen years ago, while learning Chinese language at Beijing Language and Culture University, I first encountered the local use of the term asan. In everyday Chinese vernacular, asan is often used casually, with many speakers unaware of its historical and racialised connotations. Despite this apparent informality, the term subtly conveys a cultural assertion of superiority, marking China’s perceived dominance over India. One incident during my first year as an Indian student particularly revealed this dynamic: the term asan was used to describe a friend of mine, and in that moment, it became clear how India is often visually imagined and belittled in Chinese perception.

The origins of asan date back to the late 19th, early 20th Century period, when the British colonial administration deployed mainly Sikh Indian constables to maintain order in Shanghai’s International Settlement. Distinguished by their red turbans, they were called ‘red-headed asan’ (红头阿三). The etymology of asan is often traced to a phonetic distortion of English phrases such as ‘Sir’ or ‘I say’, rendered in Shanghainese as ‘Ah-san’, following the local habit of prefixing names with ‘Ah’ (e.g., Ah-Bao, Ah-Liang). Asan also reflected the racialised labour hierarchy of the concessions; Western officers occupied the top ranks, followed by Chinese constables, with Indian officers at the bottom. This hierarchy shaped public perception, marking asan as a symbol of ethnic difference and socio-political inferiority.

Asan took on a derogatory tone through associations in the Wu dialect, where the number ‘three’ (san 三) carries negative connotations. Slang expressions like biesan (瘪三, ‘pauper’) and shisan dian (十三点, ‘foolish’) pronounced its pejorative use. Indian officers were also nicknamed ‘three-striped heads’ (三道头) for their uniform armbands, reinforcing the numerical association with social marginality. In the postcolonial era, India’s role in the Non-Aligned Movement and status as a ‘Third World’ country led to satirical references like ‘third brother’ (san ge, 三哥) in Chinese internet slang.

While some folk etymologies, such as the connection to ‘I say’ remain speculative, most scholarship affirms that the term’s origins lie in Shanghai colonial policing structure and its entanglement with regional linguistic patterns. The visible role of Sikh soldiers as colonial enforcers sparked local resentment, popularising the use of asan as a racial slur. Asan thus encapsulates a legacy of racialisation and subordination rooted in empire. Its continuity reflects how historical power asymmetries continue to shape cultural imaginaries in Asia.

In everyday Chinese usage, asan carries mocking, subaltern connotations. It functions as a racialised label across online contexts, denoting a brown, foreign, and supposedly uncivilised “other.” In nationalist spaces, it describes someone loyal yet unequal, reaffirming a hierarchy that denies parity despite solidarity. Its use in comedy and viral memes entrenches these meanings, with asan becoming shorthand for a servile, inferior, and laughable caricature. This historical baggage is amplified in the diss track.

The turbaned Indian Sikh - long perceived as a military archetype - is mocked rather than valorised, digitally echoing the colonial asan. India is framed not as a regional peer but as a neo-colonial subject: overconfident, self-important, and easily embarrassed. The meme redefines a racial hierarchy where China appears modern and superior, while India remains trapped in colonial shadows. The turbaned figure, once a colonial servant, is recast as a postcolonial fool - replicating colonial optics while inverting their context.

Asan and turban as a metonym for people of Indian origin

In India, turbans - particularly the dastar - are closely associated with Sikh identity and Punjab’s significant military contribution to the Indian armed forces. The exaggerated turbans in the video are not just comedic, they are also portrayed in ways that mock what is a key symbol of honour, valour, and pride. This satire reduces Sikh identity to a racialised caricature and reinforces stereotypes. While not overtly targeting Sikhs, the turban in this video becomes a symbolic proxy for “Indian-ness”, particularly from an external gaze.

In regional and global media, turbans often function as shorthand visual cues for “Indian”, much like the moustache, accent, or Bollywood music. Such representational shortcuts flatten the complexity of Indian identity into easily recognisable and thus mockable symbols. This form of visual simplification is convenient for satire but problematic for intercultural understanding, as it strips the turban of its religious, cultural, and historical significance. In media and cultural studies, this symbolic reduction is seen as a form of symbolic violence that trivialises minority identities. The toy aircraft atop a turban styled like Sikh headgear further distorts turban a significant element of Sikh heritage into a symbol of incompetence, enacting mimicry and ridicule. This reinforces racialised and gendered stereotypes, reflecting how memetic nationalism commodifies ethnic and religious symbols for geopolitical ends. Accent, gesture, costume, and headgear become mere tools of parody.

This phenomenon can also be understood through performative othering, where Indian identity is mocked to affirm the meme creators’ sense of superiority, in this case aligned with Chinese nationalist rhetoric. The turban with a toy aircraft visually echoes the colonial asan figure: disciplined yet laughable; militarised yet submissive. It serves political, cultural, and symbolic functions, especially during a period of conflict. While the video is restricted in India, it has been reproduced in multiple versions by local social media influencers in China and Pakistan and has circulated widely across both the countries. Chinese influencer Hao Gege has previously created memes with similarly racist depictions of Indian men in turbans and darkened faces. Meme culture in China, when read critically, reveals how history is weaponised in ways that mock former colonisers, assert postcolonial confidence, and shape new forms of national identity.

Source: Douyin (Chinese Tiktok)

The views expressed in this forum are those of the individual authors and do not represent the views of the Asia Research Institute, National University of Singapore, or the institutions to which the authors are attached.

Dr Rani Singh commenced her appointment as a Postdoctoral Fellow with the Inter-Asia Engagements and Asian Urbanisms Clusters with effect from 3 January 2025.

She graduated with a PhD in Sociology and Anthropology from the University of Western Australia in 2024 and completed her M.Phil. in Chinese Studies in Jawaharlal Nehru University. Rani’s research conceptualises transnational cultural infrastructure in relation to regional architectures of connectivity, such as China’s Belt and Road Initiative and India’s Project Mausam. At ARI she will work on the rise of civilisational politics in world affairs and the new forms of cultural infrastructure now being produced around themes of connected histories and ideas of “shared heritage”.

https://doi.org/10.25542/at1r-g819