Walking Away Diabetes in the Tropics: A Reflection

This short memo is based on my short field trips in Jogjakarta and Singapore in June and July 2025. The trip was made possible with funding from ERC COMET. I would also like to acknowledge the Asia Research Institute, National University of Singapore, specifically A/P Chang Jiat Hwee for hosting me as Visiting Scholar during this time.

16, 691 steps on that relatively cool Monday. I didn’t do much different today. I went to my office at the National University of Singapore, went for a walk around the beautifully landscaped campus at lunchtime and proceeded to central Singapore in the late afternoon, where I had a meeting with a fellow researcher at the Singapore Management University.

Walking Diabetes Away?

Exceeding the daily 10, 000 daily recommended steps, I quickly realized, was not that difficult when one is reliant on the extensive public transport network in Singapore. There are walking paths everywhere here, even covered walkways which shelter pedestrians from the frequent downpours and scorching sun.

I had made it a point to walk as much as I can during my field research trip in Singapore and Jogjakarta as a way to test the infrastructure, to see if walking can indeed be part of the solution to prevent a wide range of metabolic diseases (Muzayanah et al. 2022; Godman 2024). The pedestrian infrastructure in Singapore is markedly better than Jogjakarta. In central Jogjakarta at least, walking pavements barely exist. I also don’t remember seeing a single pedestrian crossing light in my short time in Jogjakarta. Moreover, walking to get to places is so alien to the typical Jogjakartans’ sensibilities, that my Indonesian friend remarked how I might be misrecognized by locals as an orang hilang, a lost person.

One thing that was clear in both Singapore and Jogjakarta, was how hot and humid the weather was. It made walking around uncomfortable. This was also another reason (apart from the poor walking infrastructure, Muzayanah et al. 2024 also pointed to women’s safety, which introduces a gendered component to walking) why not that many people in Jogjakarta walked. Many relied on their private vehicles or ride sharing apps to get around (Valentina 2017). Singaporeans, most of whom don’t own private modes of transportation (because it is incredibly expensive), seek reprieve in the numerous air-conditioned shopping malls to get reprieve from the unforgiving humidity and heat.

Metabolism and Heat (Regulation)

This intersection between health and heat is an increasingly important facet of public health in Southeast Asia and more broadly Asia. Honing in on just type 2 diabetes, a widespread problem in Singapore and Indonesia, studies point to how excessive heat can make it harder for individuals with diabetes to manage blood sugar levels, leading to increased risk of hypoglycemic episodes. Diabetes also affects one’s ability to cool their body efficiently, increasing the likely incidence of heat exhaustion (Westphal et al. 2010; Hoskins 2025). This association between climate and diabetes is not entirely new. Physicians in colonial India for instance, recommend long walks in ‘fresh air’ as a way to treat diabetes mellitus or madhumeha (sweet discharge) but at the same time, cautioned against prolonged exposure to heat (Roy 1907: 1058).

Broadly, heat was perceived by colonial experts such as American geographer Ellsworth Huntington as being an impediment to civilization; Asia in particular, fell within this ‘torrid zone (1915)’. Royal physician Sir R. Havelock Charles (1907) remarked that in the Calcutta climate, even the ‘Chinaman’, who physicians thought to have developed immunity to diabetes, is affected; one needed to head to the surrounding hills where it was cooler, to rest their ‘overheated machinery’ and improve their symptoms (Havelock Charles 1907:1051). In the absence of cooler hills, Singapore has resorted to cooling itself mechanically today, hence the moniker ‘air-conditioned nation’ (George 2000; Chang and Winter 2015; Clancey, Chang and Chee 2024)[1].

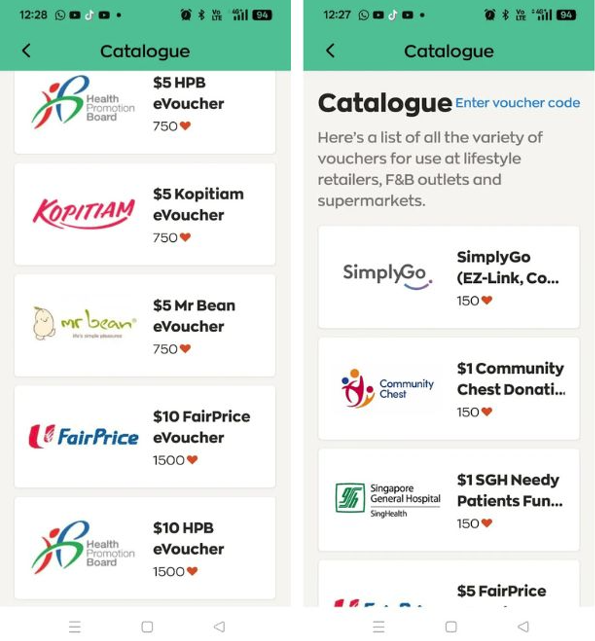

For those looking to manage their pre-diabetic or diabetic condition, or just improve their metabolic health in general, air-conditioned malls are ideal climate-controlled spaces. The Singapore Health Promotion Board has in fact gamified mall walking, promoting in app ‘rewards’ in the form of vouchers for individuals who hit their daily step targets; these vouchers can then be redeemed at specific shops in shopping malls. A Health Hub SG webpage provides a guide for how Singaporeans can make walking at malls ‘fun’, and as part of their routine. The webpage elaborates how walking in malls is not only safe, but you are ‘sheltered from the scorching sun or pouring rain’ (Healthhub.sg). The provision of climate regulated spaces therefore eliminates any excuse for not exercising one’s responsibility for maintaining metabolic health. Or does it?

Who Walks for Health?

In my conversation with a public health researcher from Universitas Gajah Mada, I brought up the absence of walking pavements and how this might be related to the rapid rise of type 2 diabetes in Jogjakarta (Karin 2024). Of course, a walkable urban environment is not the only contributing factor to this growing public health issue. The ubiquity of street stalls selling gorengan — deep-fried foods — and widespread smoking are also major contributing factors to the diabetes epidemic. “Some people still believe that smoking helps you keep slim and helps keep away disease,” the UGM researcher explained. She was sharing details from her own project investigating health behavior in Jogjakarta.

I also spoke to a health researcher from the Badan Riset dan Inovasi Nasional (BRIN), Indonesia’s national research agency. We discussed job precarity, particularly amongst workers in the gig economy and how the need to be continuously productive sometimes lead to self-medication (through the use of jamu) and delayed treatments that can lapse into severe complications and even death. Clearly, the growing problem of diabetes in Indonesia was multifaceted, with urban design and walking infrastructure being just one of many factors contributing to diabetes prevalence. Back in Singapore, my attempt to discuss walking infrastructure with low-income diabetics seemed to ring hollow. One of them remarked, ‘Who cares? I can’t even feel my legs because of my diabetes!”

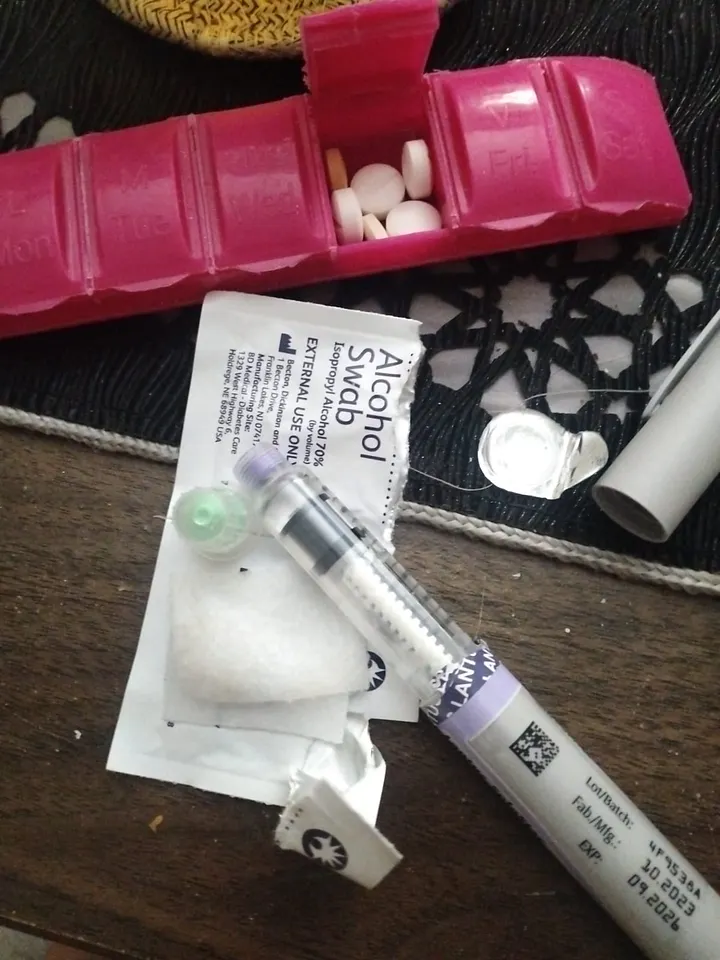

Urban design, through the creation of walkable neighborhoods and the provision of recreational spaces for instance holds the potential to promote health equity, but only when it takes into account the needs of those most affected (Tan et al. 2024). In my interviews with resource constrained individuals who have diabetes, the thing that mattered most to them were access to food, medication/treatment and mobility devices. Diabetics who are unable to afford food risk hypoglycemic episodes and even death. Diabetics who are unable to afford medication risk hyperglycemic episodes and exacerbating their symptoms[2]. Some diabetics who are resource constrained have outstanding amounts with the polyclinics or primary care providers.

How does this happen in Singapore, with its supposedly comprehensive healthcare financing system (see Bin Khidzer 2024)? Whether there is indeed a coverage gap or perhaps, some form of miscommunication in terms of how coverage for low income groups works, this gap in the healthcare financing system needs to be remedied quickly; already, some of the respondents I spoke to were looking at other avenues to treat their condition (supplements from social media) to save themselves from the embarrassment of having to face medical social workers or even worse, as one diabetic said, debt collection agencies. Public health intervention in the form of urban design and behavioral nudging (to get people to walk more as a way to prevent diabetes for instance), well-meaning as they may be, do not seem to resonate with those who are doubly disadvantaged by being chronically ill and resource constrained.

Taking the Heat off Hunger and Illness

Lina, a community leader in a low-income neighborhood showed me the community fridge initiative she started. This program serves those in the neighborhood who encounter food emergencies. Given that a third of the people who approach her team of volunteers for help are diabetic, she views this as an important service. Diabetics like herself, she explained, really need to keep an eye on their food intake and this is not just because it helps with maintaining blood sugar levels. Lina believes that the provision of healthy, nutritional food could help with preventing diabetes. “I am irritated with the fact that I didn’t take care of my health. In the past, I would go for up to a week without eating and look at what it has done to my body. I hope doing this helps people, so they don’t suffer like I do.”

For Lina, diabetes was just part of the problem. She also suffers from constant migraines and insomnia. She complained of having medical debt with the polyclinic as well. For all of her sprightly demeanor, she looked physically drained. This seemed to be an underlying theme for the low-income respondents. Was it stress or anxiety that is causing the sleeplessness, I asked? This was certainly something I had experienced at the peak of COVID, I added, trying to make myself more relatable somehow. Lina shrugged it off, explaining that she does not know. She proceeds to show me around the tiny, cramped community fridge space.

“We buy the food with help from Give Asia, and then we put them in these refrigerator and freezers,” Lina pointed out to me. Before, they had a small fridge and freezers. Then Give Asia, a social enterprise that aids community initiatives, stepped up to provide a big refrigerator. I could not help but think about the juxtaposition between hot and cold in this particular setting. The food needed refrigeration in the stifling heat. The many times I sat in the community fridge corner to conduct my interviews, I was never not sweating. Walking or not, it was just hot around here. As a colleague remarked, “It is hot because the government wants people in low-income rental housing to leave”. What was implied here was that because these forms of housing were meant to be temporary, to help people become stable financially with the goal of eventually leaving, they were not necessarily designed to be comfortable.

This is of course, an oversimplification of the situation although not entirely wrong. Where new apartments have been designed with airflow in mind, these small rental apartments, built decades ago, did not benefit from such considerations. Additionally, these small apartments are usually filled with things that impede air flow. People living in rental housing are also not able to afford temperature regulating technology like air conditioning[3]. The community fridge Lina showed me kept the food cool and safe for consumption. Yet the people who depend on the community fridge, according to a study done by a team from the Singapore University of Technology and Design (SUTD), have to endure low levels of thermal comfort (Begum and Chin 2025)[4]

Even the term thermal comfort seems to suggest that this is something that is subjective to an individual’s ability to tolerate heat, and not necessarily how their bodies, particularly bodies in the lower socio-economic spectrum that are more likely to be chronically ill, interact with heat, thereby exacerbating symptoms. Food and nutrition have grown very visible in the war on diabetes. So too has urban design. A Ministry of Health official I interviewed said that heat is not a salient consideration in the war against diabetes. Yet my fieldwork shows that the people who are most affected by diabetes also happen to live in heat spots. Perhaps it is time to recognize heat as an environmental condition that shapes illness experience and symptoms in diabetics. Heat regulation (not just through air conditioning) should not be thought of as mere ‘luxury’. Given the relationship between heat and metabolism, heat regulation should be incorporated as an integral public health tool as well.

So, walking in the heat?

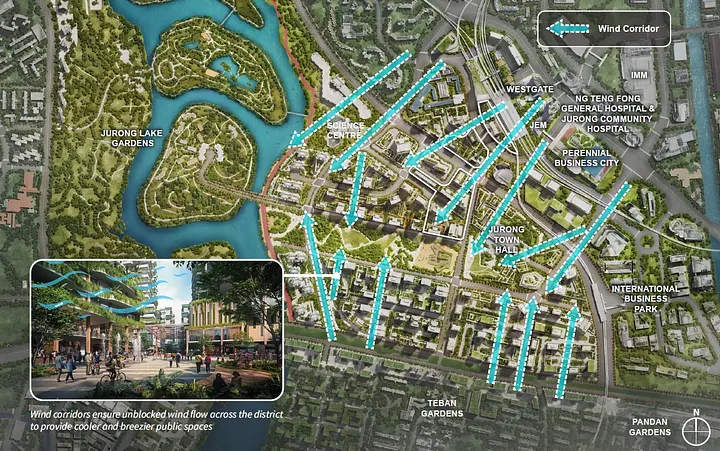

I started the essay presenting research on the health benefits of walking, particularly on one’s metabolic health. Walking as a public health strategy, as a way to prevent metabolic syndrome and diabetes, requires a combination of thoughtful and intentional urban design, and as I sought to underline here, the implementation of heat regulation technologies. These are crucial structural considerations for Singapore and more broadly, for Southeast Asia. In Singapore, the Urban Redevelopment Authority is already looking ahead, ensuring new housing estates are designed in ways that ‘harness prevailing winds’ (‘A Cool City in a Warming World’). Jogjakarta seems to have less of a problem with rising temperatures (Daeng 2025), at least for now, but as others have pointed out, the walking infrastructure and nutritional patterns can certainly be improved to combat the rapid rise of diabetes in the city. These are important considerations, particularly in parts of the world that are having to bear the brunt of climate change. Yet heat and urban infrastructure do not impact populations the same. The most vulnerable populations suffering from diabetes are still having to contend with issues such as food insecurity, on top of heat as an emergent problem. For these individuals, who need help managing rather than preventing diabetes, walking matters less than say affordable access to medicine, nutrition and increasingly heat regulation.

End

References

A Cool City in a Warming World §. Accessed July 25, 2025. https://www.uradraftmasterplan.gov.sg/themes/strengthening-urban-resilience/a-cool-city-in-a-warming-world.

Begum, Shabana, and Hui Shan Chin. “Who Bears the Heat of Climate Change? Helping Communities Deal with Rising Temperatures.” The Straits Times, April 3, 2025. https://www.straitstimes.com/singapore/environment/who-bears-the-heat-of-climate-change-helping-communities-deal-with-rising-temperatures.

Bin Khidzer, Mohammad Khamsya. “Sickly, Idle and Risky Minorities: Race and Diabetes under Singapore’s Emergent “Insurantial Imaginary”.” East Asian Science, Technology and Society: An International Journal 18, no. 4 (2024): 431–456.

Chang, Jiat-Hwee, and Tim Winter. “Thermal modernity and architecture.” The Journal of Architecture 20, no. 1 (2015): 92–121.

Clancey, Gregory, Jiat-Hwee Chang, and Liz PY Chee. “Heat and the city: Thermal control, governance and health in urban Asia.” Urban Studies 61, no. 15 (2024): 2857–2867.

Daeng, Mohamad Final. “Cuaca Panas Yogyakarta Masih Taraf Normal.” Kompas. May 6, 2024, Daily edition. https://www.kompas.id/artikel/cuaca-panas-yogyakarta-masih-taraf-normal.

George, Cherian. Singapore the air-conditioned nation: Essays on the politics of comfort and control 1999–2000. Singapore: Landmark Books, 2000.

Godman, Heidi. “Will Walking Faster Reduce Your Diabetes Risk?” Harvard Health, February 1, 2024. https://www.health.harvard.edu/diseases-and-conditions/will-walking-faster-reduce-your-diabetes-risk.

Havelock Charles, Richard Henry. “Discussion On Diabetes in the Tropics. Opening Papers.” The British Medical Journal 2, no. 2242 (n.d.): 1051–53.

Hoskins, Mike. “What to Do about Diabetes in the Summer Heat and Humidity.” Healthline, July 7, 2025. https://www.healthline.com/health/diabetes/diabetes-and-heat.

Huntington, Ellsworth. Civilization and Climate. New Haven: Yale University Press, 1915.

Karin, Alfi Annisa. “Angka Kasus Diabetes Di Jogja Melampaui Rerata Nasional, Masyarakat Diimbau Kurangi Konsumsi Gula.” Harian Jogja, September 5, 2024. https://jogjapolitan.harianjogja.com/read/2024/09/05/510/1187213/angka-kasus-diabetes-di-jogja-melampaui-rerata-nasional-masyarakat-diimbau-kurangi-konsumsi-gula.

Lee, Katy. “Singapore’s Founding Father Thought Air Conditioning Was the Secret to His Country’s Success.” Vox, March 23, 2015. https://www.vox.com/2015/3/23/8278085/singapore-lee-kuan-yew-air-conditioning.

Ministry of National Development. Accessed August 9, 2025. https://www.mnd.gov.sg/newsroom/parliament-matters/q-as/view/written-answer-by-ministry-of-national-development-on-installation-of-air-conditioning-units-in-rental-flats.

Muzayanah, Irfani Fithria Ummul, Ashintya Damayati, Kenny Devita Indraswari, Eldo Malba Simanjuntak, and Tika Arundina. “Walking down the street: how does the built environment promote physical activity? A case study of Indonesian cities.” International Journal of Urban Sustainable Development 14, no. 1 (2022): 425–440.

Roy, Rai Devendranath. “Discussion On Diabetes in the Tropics. Opening Papers.” The British Medical Journal 2, no. 2242 (n.d.): 1057–59.

Tan, Shin Bin, Andrew Binet, J. Phil Thompson, and Mariana Arcaya. “Health Equity as a Guide for Urban Planning.” Journal of Planning Literature 39, no. 3 (2024): 371–385.

Valentina, Jessicha. “Stanford Study Reveals Indonesians Laziest Walkers in the World — Health.” The Jakarta Post, July 15, 2017. https://www.thejakartapost.com/life/2017/07/15/stanford-study-reveals-indonesians-laziest-walkers-in-the-world.html.

Westphal, Sydney A., Raymond D. Childs, Karen M. Seifert, Mary E. Boyle, Margaret Fowke, Paul Iñiguez, and Curtiss B. Cook. “Managing diabetes in the heat: potential issues and concerns.” Endocrine Practice 16, no. 3 (2010): 506–511.

Footnotes

[1] Much like Huntington (1915), the first Prime Minister of Singapore Lee Kuan Yew embraced the rather orientalist notion of postcolonial development that located Singapore within global (read Western) capitalist circuits (in Lee 2015). For Lee then, civilization is unimaginable in tropical Southeast Asia, which was why technological intervention was essential A regulated, daily working temperature (and metabolism) enabled continuous productivity, a key driver of development. This historical relationship between heat, metabolism and civilization maps itself again on contemporary public health initiatives that involve walking.

[2] A social worker who serves a low-income neighborhood in central Singapore described the case of an elderly Malay man whose leg developed a lesion that wasn’t able to heal because he had diabetes. He refused to have his leg amputated and his elderly wife had to dress his wound daily. The stench of his wound, the social worker said, filled the common corridor. He died later.

[3] A researcher also informed me that aside from affordability, the older rental flats also needed to seek permission from the Housing Development Board to install air conditioning in their apartments (Ministry of National Development).

[4] The rental homes SUTD looked at had design issues such as low ceilings but they were also usually filled with things, which impeded airflow within the homes.

The views expressed in this forum are those of the individual authors and do not represent the views of the Asia Research Institute, National University of Singapore, or the institutions to which the authors are attached.

Mohammad Bin Khidzer is a Lecturer in Medicine, Health and Society in the Department of Global Health and Social Medicine, King's College London. Before joining King's he was a postdoctoral researcher at the Institute for History, Leiden University, under Dr Fenneke Sysling's European Research Council sponsored COMET project. Mohammad received his PhD in Sociology and Science Studies from University of California San Diego in 2024, where he defended his dissertation "The Making of Racialized Diabetes in Postcolonial Singapore, 1960-2020” . Mohammad’s multi-modal work has been published in Biosocieties, Science Technology and Human Values, East Asian Science Technology and Society, Eikon Positions Politics and Medium.

Mohammad is currently working on a book project examining the socio-historical emergence of 'Asian' Diabetes from Singapore. Drawing on archival research and interviews with policymakers, scientists, physicians, diabetes caregivers and people with diabetes, he traces the network of expertise involved in elevating Singapore's War on Diabetes into a global health concern, and what 'Asian' Diabetes means for Singaporeans who live with the disease. Mohammad also hopes to transform part of his research data into a living archive which places patients’ expertise – experiences, knowledge and practices - at the forefront of medical knowledge on diabetes. This forms part of his longer-term goal of partnering with communities to produce public facing, accessible and inclusive knowledge on health and medicine.

When he is not working on his research, Mohammad enjoys riding his bicycle, playing recreational football and building Legos with his 7-year-old son. He is also currently trying to learn how to make Chinese style egg tarts.