Asian Cities in Global Governance

https://doi.org/10.25542/m7zr-ceqq

As the world’s share of urban population is projected to shift from 30 per cent in 1950 to 68 per cent in 2050, society has entered into a global urban age. Even though cities cover only nearly 3 per cent of the world’s land surface, their planetary impact is unprecedented, accounting for the generation of over 70 per cent of greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions and production of almost 80 per cent of global gross domestic product (GDP).

The demographic, economic, and environmental centrality of cities in our contemporary world has amplified the potential role of city governments in global policy-making. The adoption of a stand-alone urban global goal among the UN 17 Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) or the commitment of city governments to climate targets that are more ambitious than those established by their national counterparts during the adoption of the Paris Agreement are unequivocal signs of this expanding, although still discrete, role in global governance.

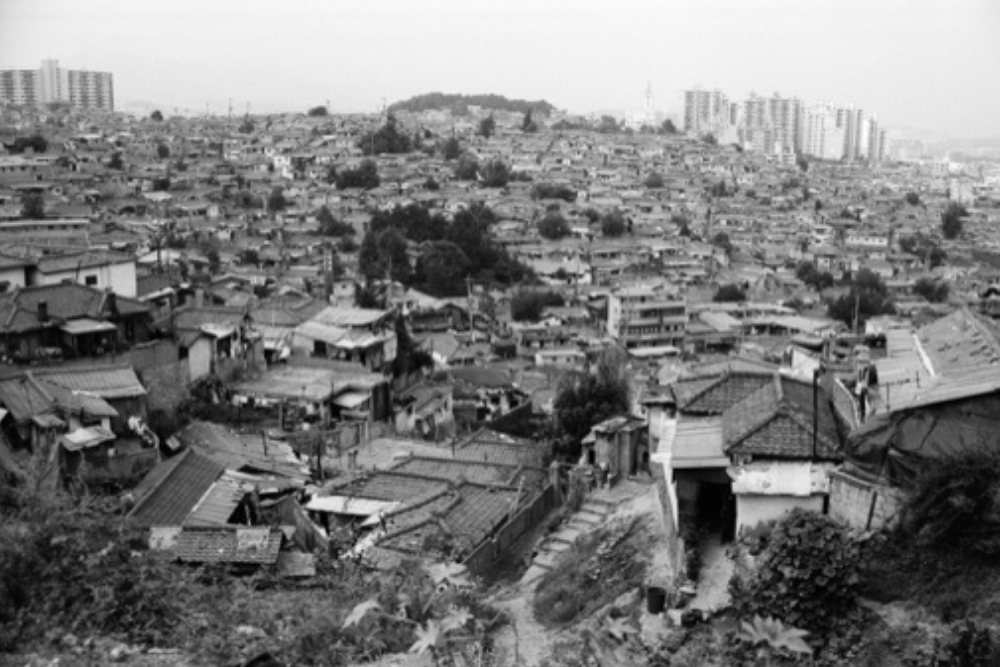

However, the geography of global urbanisation is deeply uneven, since nearly 90 per cent of the 2.5 billion new urban dwellers projected between 2018 and 2050 will be concentrated in Asia and Africa. This means that the bulk of opportunities and challenges of the current wave of urbanisation is located in cities of the global South, which present distinctive characteristics in terms of demands and capacities, and yet present significant knowledge gaps in terms of availability of urban research and data. As the region with the largest urban (and total) population of the world, understanding the urban reality of Asia and its place within the larger global governance picture is a compelling task.

Boosted by the increasing possibilities for communication facilitated by technology, globalisation has propelled the exchange of public policy knowledge across governmental actors and partners. At the same time, through a geographically uneven landscape across and within regions, numerous countries have undergone a devolution of policy decision-making processes towards subnational levels.

Aware of the value of sharing knowledge among peers facing similar challenges, city governments have increasingly connected to learn from each other in several fields of urban governance. As in the domain of climate change, they have further pooled resources in collaborative endeavours to tackle transboundary contemporary challenges and complement (and urge) national governments’ coordinated action.

This rich landscape of practices has fed the rising relevance of city diplomacy in global governance, which can be conceptualised, following Kosovac et al. (2021), as the subset of relations among city government officials as well as between city governments and nation-states, non-governmental organisations, and corporate actors. Unfurling through bilateral relations and networking configurations, the article offers a glimpse of city diplomacy in Asia, paying special attention firstly to the diversity of actors and drivers involved and secondly to the expanding place that these practices have in global governance. The latter is further illustrated by shedding light on the growing number of Asian cities that are currently monitoring the achievement of the SDGs within their cities through the development of the Voluntary Local Reviews (VLRs), which were officially presented to the international community for the first time by three Japanese municipalities (i.e., Kitakyushu, Shimokawa, Toyama) along with New York City in 2018.

Asian cities gazing beyond their national (and regional) borders

The international action of Asian cities mirrors the region’s remarkable diversity. Its variance in terms of socio-economic development and political institutional contexts, embedded in the region’s vast population and geographical extension, outlines a heterogeneous landscape in which city diplomacy unquestionably moves at different speeds.

The region encompasses quintessential global cities such as Seoul and Singapore which, in addition to hosting the corporations that interweave the global interconnected economy, are inherently transnational in their governmental action—discernible in the significant resources that these cities invest in for promoting their policy expertise regionally and globally in areas of urban governance such as water management and age-friendly preparedness. There is often a blurred line between competition and collaboration among cities, which actually fuels their international dynamism, as exemplified by the close collaboration between the two main institutions in charge of promoting each city as an urban model in the competitive marketplace of policy expertise: the Seoul Institute and Centre for Liveable Cities, respectively.

Somehow moving away from the dynamism of iconic global cities, an additional layer to disentangle city diplomacy in Asia is constituted by national local government associations, particularly in light of the fundamental role they play (or should play) in supporting small- and medium-sized cities, which are at the centre of the current wave of urbanisation. The most inspiring experience in this regard is LOCALISE SDGs, a collaborative programme by United Cities and Local Governments Asia Pacific (UCLG ASPAC) and the Association of Indonesia Municipalities (APEKSI), funded by the European Union (UN), which has strengthened the technical and institutional capacities of local governments and local government associations to achieve the SDGs. The programme has provided training sessions to help integrate the SDGs into the local development plans, targeting initially 16 provinces and 14 cities in Indonesia, but then extending to a wider outreach within the country.

Of course, the transnational ventures of Asian city governments are influenced by wider power relationships, not least the state-centric international politics in which they are embedded. An example of this is the decision by the Prague city government to cancel a sister-city agreement with Beijing city government and replace it with Taipei city government, as the Czech city did not accept the Chinese city’s attempt to include in the partnership agreement a clause endorsing the ‘One China’ principle (to which the Shanghai city government responded by suspending official contact with the Czech city).

Yet these transnational endeavours, and in particular when amplified by networks, provide cities with a ‘launch pad’ to access policy scales beyond their local jurisdiction and national borders. This is the case, for instance, of Gwangju that has been holding the annual World Human Right Cities Forum since 2011 as a specific networking platform that advocates for the recognition of cities as key players in promoting human rights. Furthermore, city networks offer simultaneously a launch pad for city leaders as individual political representatives, as exemplified by the trajectory of Maimunah Mohd Sharif, who is the current Executive Director of the United Nations Human Settlements Programme (UN-Habitat), the UN agency in charge of cities, and former Mayor of Penang Island and an active member of the global networks.

Yet the clearest example of the contribution of regional city diplomacy to global governance is provided by the VLRs. In the context of the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development agreed upon in 2015, states are reviewing the national implementation of the SDGs through the Voluntary National Reviews (VNRs). Despite not having an official mechanism within the UN institutional architecture, city governments from across the world, from both the global North and global South, are developing their own VLRs to assess the achievement of the SDGs in their cities.

So far, 21 VLRs or similar local reviewing documents have been published in Asia: 3 in China, 1 in Indonesia, 6 in Japan, 2 in Malaysia, 1 in Philippines, 2 in South Korea, and 6 in Taiwan. By aligning local policy-making to the global agenda on sustainable development, the VLRs are more than monitoring mechanisms, as they can help foster civic participation, emphasise the role of subnational governments in national commitments, and provide a platform for peer learning among outward-looking city governments. The VLRs in Asia depict a variegated landscape of cities, big and small, and their way of understanding their local contribution to global challenges—from Shimokawa, a Japanese town of less than 4,000 residents that engaged its whole community with the support of local advocacy groups in the elaboration of the municipal strategy for sustainable development, to Guangzhou, a megalopolis of more than 12 million inhabitants that has adopted around 70 measures in response to the SDGs, which are, in turn, aligned to the 2035 strategic plan of the city.

With at least 110 VLRs or similar reviewing documents published up to date by local governments from over 30 countries, the support of global city networks and international organisations, in particular UCLG, United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs (UNDESA), and UN-Habitat, is consolidating the diffusion of this policy tool. Regionally, the United Nations Economic and Social Commission for Asia and the Pacific (UNESCAP) is providing practical guidance for subnational governments conducting VLRs. A significant role has been played by the Institute for Global Environmental Strategies of Japan (IGES), which, in addition to collecting local review practices, has assisted Japanese cities in the elaboration of their reports since the first-ever VLRs were presented at the UN in 2018.

This initial broad-brush account of the contribution of Asian city diplomacy to global governance can help take the pulse of a phenomenon that will certainly gain relevance in the coming decades along with the rising centrality of urban Asia on the world stage. It is further particularly relevant in terms of academic research agenda since city networks and partnering international organisations are currently the main referents for the exchange of policy knowledge for decision-makers and practitioners of city governments in the global South, particularly in low- and middle-income countries.

The views expressed in this forum are those of the individual authors and do not represent the views of the Asia Research Institute, National University of Singapore, or the institutions to which the authors are attached.