Bilateral Cooperation in Higher Education between China and Thailand for the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI)

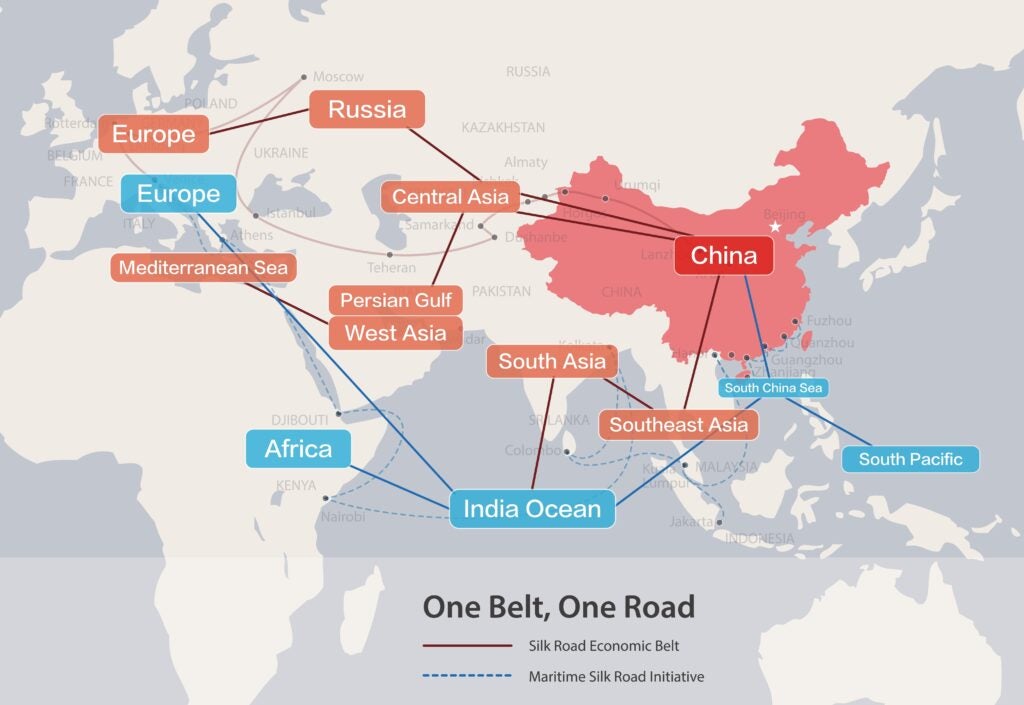

Since Chinese President Xi Jinping’s announcement in 2013, the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) has received much attention from many scholars who have examined it through various perspectives including economics and geopolitics. Previously known as One Belt, One Road (yi dai yi lu), the BRI is an ambitious mega-development project that consists of two parts—the Silk Road Economic Belt and the 21st Century Maritime Silk Road. The aim of the BRI is to promote “peace and cooperation, openness and inclusiveness, mutual learning and mutual benefit” among countries in different regions (such as Southeast Asia, Africa and Europe) through large infrastructure development plans on land and sea. Since 2013, more than 140 countries in different regions have indicated their interest in participating in the BRI by signing Memorandums of Understanding (MOUs).

Map illustrating the extent of the BRI. Shutterstock.

One example of the large infrastructure development project is the China-Laos Railway which began operating on 3 December 2021. Passenger trains depart from Kunming, a city in Yunnan province, China, for Vientiane, the capital of Laos. This railway would eventually be extended further into Thailand through another high-speed railway project under the BRI. Running between Kunming and Vientiane, the passenger and freight train is more than 1000 kilometres (km) long and is expected to cut travel time between the two cities to about 10 hours. Prior to the completion of the China-Laos Railway, travelling by coach between Kunming and Vientiane could take about a day. As such, the railway project was promoted by state media in Laos as an important strategy in transforming Laos from a landlocked country to a land-linked one. However, mega-development projects such as the BRI are not without criticisms from economists and politicians. A common criticism of the China-Laos Railway by economists, for example, is the high external debt that Laos (one of the poorest countries in Asia) is saddled with and needs to repay.

In response to criticisms of the BRI, China has claimed to maintain its commitment to promote win-win cooperation among the participating countries and to follow the principles of extensive consultation and joint contribution to ensure openness, inclusiveness and transparency. To facilitate the development of the BRI in Thailand, Thai and Chinese state firms have signed agreements in 2017 to extend this high-speed railway project from Laos to Bangkok, from the mid-2020s. Efforts have also been made between both countries to train vocational students to work on the railway’s maintenance in the future.

An electric train operating along the China-Lao Railway, arrives at Yuxi Railway Station in Yunnan Province, China. Source: Xinhua/Hu Chao.

China has focused on both the “hardware” and “software” components to increase connectivity under the BRI. The “hardware” component of the BRI refers to physical infrastructures, including the planning and construction of high-speed railways, ports and roads. The “software” component, on the other hand, is about encouraging cultural exchanges and strengthening people-to-people bonds or connections. In particular, to increase people-to-people exchanges, China intends to deepen integration in education along the BRI routes. As such, the Education Action Plan was implemented in 2016 to integrate education and development, and to strengthen win-win cooperation between different countries. Exchanges through education “serve as a bridge to closer people-to-people ties, whereas the cultivation of talent can buttress the efforts of these countries toward policy coordination, connectivity of infrastructure, unimpeded trade, and financial integration along the routes” (Education Action Plan [in Chinese], website of the Ministry of Education of the People’s Republic of China).

I examine the bilateral cooperation in education between China and Thailand that supports the development of BRI through higher education institutions and the establishment of vocational institutions. I focus on China and Thailand because they have established diplomatic relations for many years (since 1975) and through their long-term friendship, have cooperated in many areas including politics, economy and education. Thailand, for instance, is the most preferred destination in Southeast Asia for the setting up of Confucius Institutes (CIs) and has hosted 37 CIs by 2018. CIs are non-profit institutions, which aim to share and promote the learning of Chinese language and culture on a global scale. Thailand had also launched the CI of the Maritime Silk Road, named after the BRI, and is committed to the development of comprehensive strategic bilateral cooperation between China and itself.

Bilateral Educational Cooperation between China and Thailand

On 24 and 25 September 2021, the 3rd Forum on China-Thailand Higher Education Cooperation and the 2021 Alliance of China-Thailand Universities (ACTU) Assembly was held with more than 360 attendees from over 140 universities in China and Thailand. Established in 2020, the ACTU is committed to promoting higher education exchanges and cooperation between China and Thailand within the framework of the development of the BRI and the national development strategy of Thailand. There were two important outcomes of this event. Firstly, several memorandums of understanding (MOUs) were signed between universities in China and Thailand. For example, Jiangsu University and Chiang Mai University signed an MOU to jointly establish an international laboratory, while Beijing Language and Culture University and Siam University signed an MOU to jointly establish a Chinese language international college. Furthermore, in-depth discussions and exchanges were conducted during the China-Thailand University Presidents Forum to promote and expand bilateral education cooperation between China and Thailand with respect to the BRI.

Encouraged by ACTU, exchanges between higher education institutions in China and Thailand were deepened, especially in areas concerning research and the training of international talents to support the BRI. To support the development of the BRI in Thailand, vocational colleges from Thailand and China collaborated in training and preparing students for the eventual operation of the China-Thailand railway. In March 2016, Tianjin Bohai Vocational Technical College established the Lu Ban Workshop in Ayutthaya Technical College in Thailand. This is the first Lu Ban Workshop located outside of China. The Lu Ban Workshop project was named after the father of Chinese architecture and patron saint of Chinese builders and contractors, Lu Ban, who lived around the 4th century BC. Over the next two years (2016-2018), more than 2000 students received technical and vocational training through the Lu Ban Workshop, to be employable in the BRI projects. Furthermore, the collaboration between the vocational colleges in Tianjin and Ayutthaya encourages student exchanges between China and Thailand. The mutual recognition of academic qualifications also allow students trained in Thailand to find work in China and vice versa.

Bilateral cooperation in developing railway talent continued in 2019, when the Banphai Industrial and Community Education College in Thailand and Wuhan Railway Vocational College of Technology in China collaborated to establish the Lu Ban High-Speed Railway Institute, to train students to become drivers or engineers for the high-speed railway in Thailand. In this respect, the bilateral cooperation in education between China and Thailand directly contributes to the fostering of talents for the operation and management of the high-speed railway.

Students practising on a train simulation with Lu Ban High-Speed Railway Institute. Source: Xinhua/Lin Hao.

On one hand, the numerous MOUs signed between higher education institutions demonstrate that China is developing a strategic plan to expand the scale of international education by engaging more universities as well as vocational institutions to meet the sustainable development needs of the BRI. The attention paid to educational cooperation between China and Thailand suggests that young people (students) are considered important participants in the BRI. By focusing on training students to operate and manage high-speed railways, young people are seen as future drivers of the BRI to advance development and cooperation. Students from Thailand also seem interested in the development of the BRI and actively participate in courses related to high-speed railway operation. For example, Kantithat Danaut, a student from the province of Nakhon Ratchasima, Thailand, said that he “want[ed] to bring what I have learned in China about railways back to serve in Thailand” after attending an eight-month joint training programme for operating the high-speed railway at Wuhan Railway Vocational College of Technology. Preeyaporn Kaenavong, a student of the Lu Ban High-Speed Railway Institute, also spoke about her excitement about going to China to “continue my study and board a high-speed train to experience the speed”. These responses were in line with the commitments made under the Joint Communique of the Leaders’ Roundtable of the Second Belt and Road Forum that was held in April 2019 in Beijing, China. To advance people-to-people exchanges, one of the commitments made was to “emphasize the importance of strengthening cooperation in human resources development, education, vocational and professional training, and to build up the capacity of our peoples to better adapt to the future of work, so as to promote employment and improve their livelihoods.”

However, collaboration in the BRI is not all positive. Scholars have argued that the BRI leads to a geopolitical transformation of higher education. Beyond the expansion of China’s political and economic reach that is often discussed in the media, researchers on the BRI also note that there are alternative narratives and imaginaries to the economic opportunities brought about that are not yet evident. For example, researchers have examined alternative narratives of the BRI from students from other countries such as Malaysia and highlighted their suspicions of China’s motives. We can ask similar questions about the ongoing development of the BRI in Thailand: are there any alternative narratives among the students in Thailand and how do they affect student perceptions of the BRI? Does bilateral cooperation in education affect how students from China and Thailand relate to each other? More research is needed to further our understanding of the implications of the BRI in Thailand.

What is next?

While a large portion of the literature on the BRI has focused on the economic, political, and environmental implications of the BRI, few scholars have looked at its implications on people-to-people exchanges and connections, which are of great importance to the Chinese government. Fewer still have studied how bilateral cooperation is implemented by the governments in countries along the BRI routes to promote linkages in higher education (including vocational training), especially those that aim to facilitate and support the development of the BRI. While the positives are clear, more needs to be done to reflect the perspectives (and alternative narratives) of Thai students and Thai society at large. Going beyond the narratives presented by the governments would offer a more nuanced understanding of the impact of the project.

Since the beginning of 2020, the global COVID-19 pandemic has disrupted logistics worldwide and affected the progress of the BRI projects. Policies that restrict movement across borders have also disrupted global migration. In this respect, the time is ripe for further research on the role of young people in the BRI, their perceptions of the mega-development project and the implications of the project on their lives, especially during this time of uncertainty and disruption.

The views expressed in this forum are those of the individual authors and do not represent the views of the Asia Research Institute, National University of Singapore, or the institutions to which the authors are attached.