City tour – Explore an old building in Singapore

https://doi.org/10.25542/v21x-np5j

As an integral part of the city, Singapore’s old buildings document the city's past, accompany people growing up, and impact the urban future. These buildings include a temple with records of early Chinese immigration, a gallery that witnessed British colonial history, or may even be an old house where your parents lived.

Many old buildings form a distinguished backdrop to the trend of sharing photos and video on social media, In addition, buildings with traditional architectural styles are becoming popular check-in locations.

To share influential posts, you would be curious about the story beyond the old buildings, or need a deep understanding of architecture. This article may provide you with some ideas for the following old buildings as destinations to share.

Destination 1: Chinese-style Temple

Locate a Chinese temple

According to the author’s research, there is more than one Chinese temple per each square kilometre in Singapore, making it easy to locate a Chinese temple in your neighbourhood. Distinct from modern buildings, Chinese-style temples give us haunting visuals in the metropolitan space of skyscrapers surrounding us. Usually, Chinese temple architecture adopts the traditional Chinese style of red walls and big roofs with yellow tiles, especially for Buddhist temples.

In fact, many Chinese temples in Singapore are new constructions that mimic Chinese temples, although they appear to have traditional Chinese-style architecture. These Chinese-style temples manifest more intangible religious cultural heritage rather than authentic tangible built heritage in its strict sense.

A case in point is the Buddha Tooth Relic Temple in Chinatown, officially opened in 2007 for tourism development which was built in the architectural style of Buddhist temples of China's Tang Dynasty, as shown in Fig. 1. As a popular tourist destination, it attracts many visitors (believers and tourists). A female in her thirties says:

‘I am a freethinker, my visit is just for a tour, not related to the religion, so I don't know the history of the temple.’

A male visitor in his twenties says:

‘I am from Malaysia, I tour with my two friends and follow a tourist blog…Yes, I know Thian Hock Keng, it was mentioned in the blog, but it's too far away. We have to leave.’

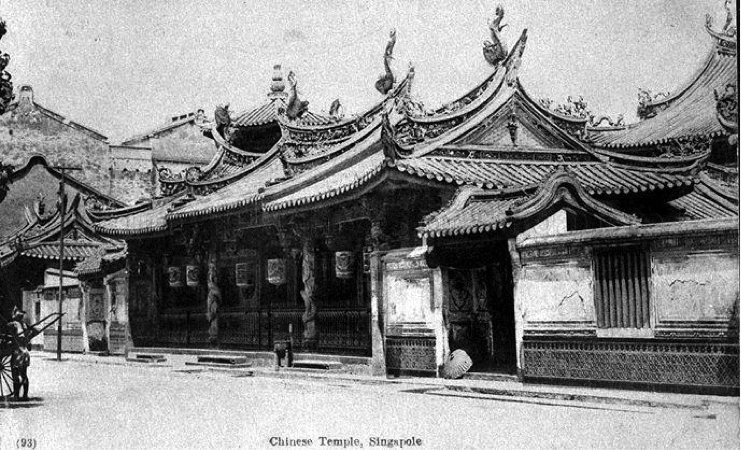

Thian Hock Keng Temple, located close to the Buddha Tooth Relic Temple, is an excellent example of a Minnan architectural style temple (also Hokkien architecture). As one of the most historic Chinese temples in Singapore, it was originally built in the 19th century by Chinese immigrants. Today, its Minnan architectural style remains, including its single-storey design with a large yard.

Still, most of the original materials have changed after restoration during different times, as shown in Fig. 2 and Fig. 3, such as the swallowtail roof, wooden columns, and gorgeous colourful ornamentation. When asked about the authenticity of the temple, a male visitor in his 30s answered:

"I don’t know what authenticity is, but I think this temple is old and not new. You can see the old roof, old wall, and know that the temple was near the sea many years before. It’s with a long history."

A local male vendor said:

"Of course, Thian Hock Keng is the oldest one, but everyone is busy with work, so they go to the nearest temple and do the religious activities…Whether the temple is old or new is not important, we just create spiritual sustenance."

Sharing an architectural photo

You may find it hard to take a photo of the temple with an entire blue sky as background because of the high-rise buildings surrounding it. It is also interesting to view these images filled with traditional architecture against the modern as architecture of Singapore.

Moreover, an enlarged view of the decorations and ornamentations of the temple architecture could enrich your photo sharing, such as an inscription on the plaque, ornate roof decorations with the Chinese dragon, and stone lion at the entrance, as shown in Fig. 4. When shared online, you would then be a producer of digital heritage.

Listen to an elder’s story

It is well known that Chinese immigrants of the past play a pivotal role in the history of Singapore. The official story has been written in textbooks. In contrast, some folk tales and legends may remain in the memories of your grandparents and the elderly family member; and even the remarkable story of the time your forefathers immigrated from China or an episode when they were young. In addition, a pleasant weekend could consist a family visit to temples and listening to their stories. All these could complement your photos.

Destination 2: Colonial buildings

Meet with museums and galleries

The colonial legacy of the British colonial period (1819-1942 and 1945-1963) is another big part of Singapore's urban heritage landscape and tourist resource. Influenced by the British architectural style, these colonial buildings adopted a western-style design of contiguous arches, white exterior walls, oversized windows, and gorgeous decoration.

Significantly, the grass lawn around the building created precious green spaces between the high-rise buildings, such as in Gillman Barracks, as shown in Fig. 5. Gillman Barracks, initially a military barrack complex built by the British in 1936, was renovated and reused as a cluster of commercial art galleries in 1996.

The most famous example is the National Museum of Singapore, the building has a history dating back to the former Singapore Library built in the 1840s. It is one of the most famous museums in Singapore’s history and a popular tourist destination. A variety of Doraemon figures on its grass lawn attracts people to take photos with them, making the heritage museum a more fun place to visit.

Moving from outside to inside

Today, most colonial buildings have been transformed and reused as museums and galleries opened to the public. After their transformation, the old buildings usually retain their external colonial architecture according to the heritage reuse principle. However, to meet exhibition and display needs, the indoor space usually gets a new look, with showcases, repainted walls and bright spotlights. With the value of colonial heritage created by reuse, visitors can enjoy historical heritage architecture and learn from the exhibitions and displays.

The current National Museum of Singapore exhibition - Home, Truly- Growing up with Singapore, 1950 to present - recalls childhood memories of different generations with old objects and artefacts, as shown in Fig. 7. The ‘briefly, educationally, and informatively’ historical narrative has received high praise from visitors.

At Gillman Barracks, besides appreciating the excellent artworks, the 6.4 hectares cover a sizeable green land around the buildings as a perfect place for relaxing and walking, becoming a quiet, peaceful, and cooling space within a bustling urban life.

Share your expectations

With the government and civil society's efforts, many old buildings in Singapore, besides those mentioned in this article, have been transformed into various urban heritage spaces. However, they may not align with your expectations, and we would like to hear from you. Your feedback will contribute to our research on heritage improvement.

For example, is it vital to repair an old building built with original materials? Can it be seen as an old building if it has been reconstructed with its original appearance retained? Do not hesitate to connect with us by emailing aridz@nus.edu.sg and voice your ideas.

Correction: An earlier version of this article incorrectly reported that the National Museum of Singapore building goes back to 1887. This has been corrected to 'has a history dating back to the former Singapore Library built in the 1840s.'

Correction: It was incorrectly stated that the the Thien Hock Kheng dragon pillars (granite) were replaced. They were in fact changed to wooden columns.

Correction: The Buddha Tooth Relic Temple and Museum (BTRTM) was not built in 2003 as stated. The BTRTM was officially opened in 2007.

The views expressed in this forum are those of the individual authors and do not represent the views of the Asia Research Institute, National University of Singapore, or the institutions to which the authors are attached.