Endangered theatrical practices: A study of Hokkien theatre across the seas

“Language is the road map of a culture. It tells you where its people come from and where they are going.”

Rita Mae Brown

Growing up in a family that speaks Hokkien and Teochew (other than Mandarin), these different Chinese vernaculars (fangyan, known in Singapore as ‘dialects’) feel close to my heart since childhood. My grandmother, a native from Swatow, China, would often play Teochew songs (qu/kêg4) on Rediffusion, a cable-transmitted radio station popular in Singapore in the mid-twentieth century.[1] *As I grew older, I felt that these regional languages are hardly spoken among the younger generation and losing their significance as older speakers passed on. The mission to document regional culture, specifically theatre, became an important part of my research.

Across the Seas

For my monograph Hokkien Theatre Across the Seas: A Sociocultural Study, the “Across the Seas” concept was chosen for the following reasons.[2] Since the eleventh century, Quanzhou (part of south Fujian, China), where many of the Hokkien (Minnan) migrants originated from, was a thriving trade centre reputed to be ‘The Emporium of the World.’

The Hokkien living in south Fujian were a littoral community who relied on the seas for a living and would travel across the seas especially during forced circumstances. The sea/water is regarded as a fluid channel facilitating regional interaction as the Hokkien migrated to various locales. These locales, as covered in the book, include Kinmen (Quemoy), Taiwan and Singapore, where the majority of the Chinese population could trace their ancestry to south Fujian.

With Hokkien as a common language (Kinmen as Jinmen hua/Kim-mn̂g uē, Taiyu/Tâi gí in Taiwan and Fujian hua/Hok kiàn uē in Singapore) and with their ancestral origin from south Fujian, these locales interacted with one another, forming a regional network that surpassed political domains marked out by ‘land-bounded’ societies. Hence, the ‘across the seas’ concept is useful in understanding such regional interaction, which has facilitated the transmission of theatrical forms brought by early migrants to their sites of sojourn.

In the initial stage of migration (the three sites experienced different periods of mass migration), theatrical forms from south Fujian were ‘transplanted’ to the migration locales, that is, troupes from south Fujian travelled frequently to these sites to perform. Gaojia opera, for example, was well-received by the migrant populations in Kinmen, Taiwan and Singapore.

Far away from home in a foreign land, these theatrical forms originally from the migrants’ hometown served to soothe their homesickness, including Gaojia opera and puppet forms—glove puppet theatre (budaixi/potehi) and string puppet theatre (kuileixi/kaleihi).[3] Similar to human actor opera like Gaojia opera, potehi also served its entertainment purpose. Kaleihi, on the other hand, is known for its liturgical nature, particularly to ward off malevolent forces that may bring harm to mortal beings.

Made Locally

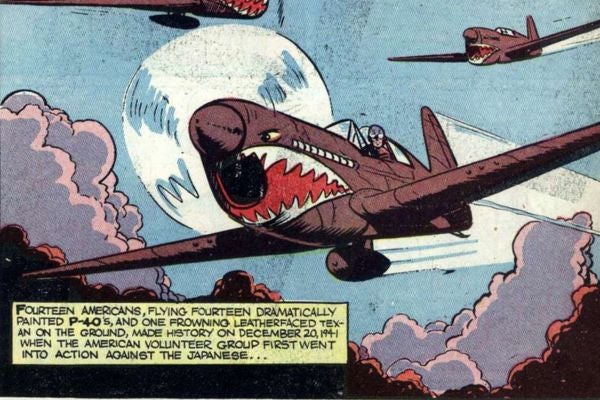

While the ‘Across the Seas’ theory is important in understanding regional interaction, the socio-political development in these land-bounded societies should not be ignored. The end of the Second World War contributed to heightened consciousness among the sojourners-turned-residents in their host societies. They became more emotionally and socially attached to their new-found homes, especially when affiliations with their ancestral homeland were altered. Moreover, the newly established governments in all three sites imposed various regulations that impacted on theatrical practices.

In 1949, Taiwan came under the control of the Republic of China (ROC) government. The ROC, represented by the Nationalists/Kuomintang (KMT), was involved in a civil battle with the Communists/Chinese Communist Party (CCP) who founded the People’s Republic of China (PRC) in mainland China. This eventually led to their involvement in the Cold War tension and the Nationalists’ slogan was ‘Repel the Communists and resist the Soviets’ (fan gong kang e). The popularity of potehi was targeted by the Nationalist government and special glove puppets were produced for this propaganda.

Kinmen, on the other hand, was what I termed the ‘militarized ‘time capsule’’ because it served as a critical base for the Nationalists to reclaim mainland China and a line of defence for Taiwan. This resulted in its heavy militarisation until the martial law was lifted in 1992. Such militarisation, I argue, isolated Kinmen from the rest of the world, including to some extent mainland China and Taiwan, and helped to retain many of the Hokkien/Minnan characteristics of the 1950s and earlier.

For example, string puppet theatre remains an essential component of the everyday lives of the Kinmen people whereas in Taiwan, many string puppet troupes faced the challenge of sustaining their trade as the demand for liturgical rituals conducted by string puppet theatre dwindled.

In Singapore, the population comprises of diverse groups of various ethnicities. For example, the Straits Chinese, who spoke a mix of English, Malay (Peranakan Malay) and Hokkien, street entertainment had to cater to a wider group of audiences who may not necessarily be of Hokkien ancestry. This situation, in contrast to Kinmen and Taiwan, partly contributed to the rise of Gezai opera, a cultural import from Taiwan.

From the late nineteenth century to early twentieth century, Gaojia opera from south Fujian, known for its martial stunts, was a popular form of entertainment for the migrant Chinese (Hokkien) population on this island state. The increasing popularity of Gezai opera gradually overshadowed Gaojia opera, as the latter was sung in classical Hokkien.

By contrast, the easy-to-understand ballad style of Gezai opera attracted larger audiences, even among those who only had a general command of Hokkien. Not only did Gezai opera become the dominant opera form in Singapore, it also influenced puppet theatre. Both potehi and kaleihi made the conversion from performing Nanguan music to the Gezai tune. This transformation in puppet theatre, which I term the ‘Gezai opera style’ puppet theatre gradually lost its liturgical function as many of the current string puppet troupes lack the religious know-how to conduct related rituals.

Documenting endangered theatrical practices

Other than tracing the development of Hokkien theatre in Taiwan, Kinmen and Singapore through historical and archival sources, fieldwork constitutes another key component of this research. There is urgency to document existing theatrical practices in these sites as they are increasingly endangered. Fieldwork observation allows for the comprehension of actual practices and examines factors that contributed to differences in these sites even though they share the same ancestral link.

For fieldwork conducted in Kinmen (2016), Taiwan (2013 and 2016) and Singapore (2004-2018), Kaleihi was chosen as the subject focus for the following reasons. It enjoyed a higher social standing compared to other Hokkien theatrical genres (Gezai opera, potehi). However, the belief for the efficacy of this puppet theatre has declined in contemporary times and faces the challenge of attracting younger successors to sustain the tradition.

String puppet theatre in Kinmen enjoys a high standing and is regularly performed during the Pacification offering (dian-an) or ‘Offering of Celebrating Completion’ (qingcheng jiao). The purpose of the Pacification Offering is to ensure that the environment/earth (tu) is secured or pacified after a new building or temple is established or an old construction is restored.

One reason for the frequency of such events is the destruction and heavy casualties suffered by Kinmen during the battles fought between the CCP and KMT. Many old lineage halls, temples and residential houses were destroyed as a result. The string puppet performance in the Pacification offering is known as ‘Theatre of suppressing malevolence’ (zhishaxi). Chief Marshal Tian (Tiandu yuanshuai), the God of Theatre, is invited as he is the chief exorcist for this theatre. Four generals, possibly representing Wen, Kang, Ma and Zhao, appeared as martial puppets armed with swords, were invited one by one and positioned at the sides of the stage, believed to guard off any malicious forces.

Next, Master Yang T’u-Chin of the Chin Liang-hsing puppet troupe held on to a sword, brought a white rooster to the centre of the stage where he prayed to Chief Marshal Tian. The sword was used to slit the rooster’s crown and a brush was used to dab the blood and write talismans. The rooster’s blood is believed to have spiritual power to curb malicious forces. The use of talismans, three-coloured cloths, rooster’s blood, invitation of Chief Marshal Tian and the four generals highlight the need to prevent disruption by malevolent forces. The ‘Theatre of suppressing malevolence’ is strongly attached to the lineage system emphasized in Kinmen, which includes the expelling of possible negative forces that may harm occupants of the lineage hall.

In Taiwan, the practice of executing the exorcistic function of string puppet theatre is rapidly declining. At the time of my fieldwork in 2016, the Ching Ch'un T'ang Puppet Theatre Company was the only troupe still performing this exorcistic rite. The chief puppeteer is Master Lin Chin-Lien who invites the exorcist deity Zhong Kui, believed to have demon-quelling powers to expel malevolence present in unnatural deaths.

The belief is that those who suffered from unnatural deaths, such as drowning, car accident, murder or suicide, would wander at the site where the death occurred to find a replacement (zhua jiaoti). The ‘Exorcistic Dance of Zhong Kui’ is performed to guide these wandering spirits to their appointed spaces.

As mentioned earlier, the string puppet theatre in Singapore is mostly transformed to what is known as the ‘Gezai opera style puppet theatre’ where most puppeteers do not conduct any liturgical (traditional) function of the theatrical form. However, from my observations, the exorcistic role of this theatre is still performed by Jit Guat Sin and Chew Yee, though the frequency of such performances is rapidly decreasing.

Two particular rites still conducted today are ‘Opening the Temple Door’ (kaigongmen) and “The Complete Performance of Su” (also known as Mosu/Mor Sor). The former is usually performed during the consecration of a new temple, whether it is newly constructed or an existing temple that has moved to a new site. In both rites, Chief Marshal Tian is invited to perform the ritual.

On a final note, this ‘Across the Seas’ concept remains an important part of my post-monograph research. While the three sites mentioned above have displayed distinct characteristics of sustaining Hokkien theatrical practices, there are other locales that also belong to the Hokkien network. One example is the Philippines, where migrants from south Fujian settled as early as the sixteenth century.

I argue that Nanguan, a musical form from south Fujian, remains a significant marker of Filipino Chinese identity and allows for the sustenance of Kaoka (Gaojia opera) whereas it has ceased to exist in other parts of Southeast Asia. This study on Kaoka will be published in Sinophone Southeast Asia: Sinitic voices across the Southern Seas.

[1] The ethnic Chinese population in Singapore traces their ancestry mainly from the Fujian and Guangdong provinces in south China. From the mass migration wave beginning in the late nineteenth century up till the 1980s when I was born, most of the ethnic Chinese could speak their ancestral vernaculars (more commonly known as ‘dialects’ in Singapore), which could be Hokkien, Teochew, Cantonese, Hainanese or Hakka etc. The encouragement of using Mandarin (huayu) as the lingua franca among the ethnic Chinese meant that the use of these ‘dialects’ became less common, especially among the younger generation.

[2] The “Across the seas” concept, as highlighted in this monograph, builds upon Brian Bernards’ “archipelagic imagination”. In contrast to the “archipelagic imagination” is the “continental imagination”, where political domains are often marked out or restricted by land boundaries, but the maritime concept denotes fluidity, allowing the regional culture(s), in this context the Hokkien, to go beyond different ‘land-bounded’ societies and share a common (regional) language and culture.

[3] For terms in italics and parentheses, the Mandarin version appears first, followed by Hokkien (if available).

The views expressed in this forum are those of the individual authors and do not represent the views of the Asia Research Institute, National University of Singapore, or the institutions to which the authors are attached.