Film censorship and Singapore’s national imaginary

How are we to understand Singaporean filmmaker Ken Kwek’s statement that the ‘average citizen’ scares him? Drawing on an article I published earlier this year, I would like to reflect

on how identity politics influences film censorship in Singapore and instils much uncertainty in the everyday work of filmmakers and censors alike.

As the cinema of a small nation, Singapore cinema punches above its weight. Alongside a steady rise in the number of local films produced since 2010, more and more of them have performed well in international film festivals. Notable mentions include Anthony Chen’s Ilo Ilo (2013) that won the Caméra d’Or award at the Cannes Film Festival and Yeo Siew Hua’s

A Land Imagined (2018), which bagged the Golden Leopard at Locarno Film Festival.

The close links between government funding and film production in Singapore raises questions about the issue of censorship. So how is censorship playing a role in shaping Singapore’s new wave of filmmaking?

Censors as participants in film expression?

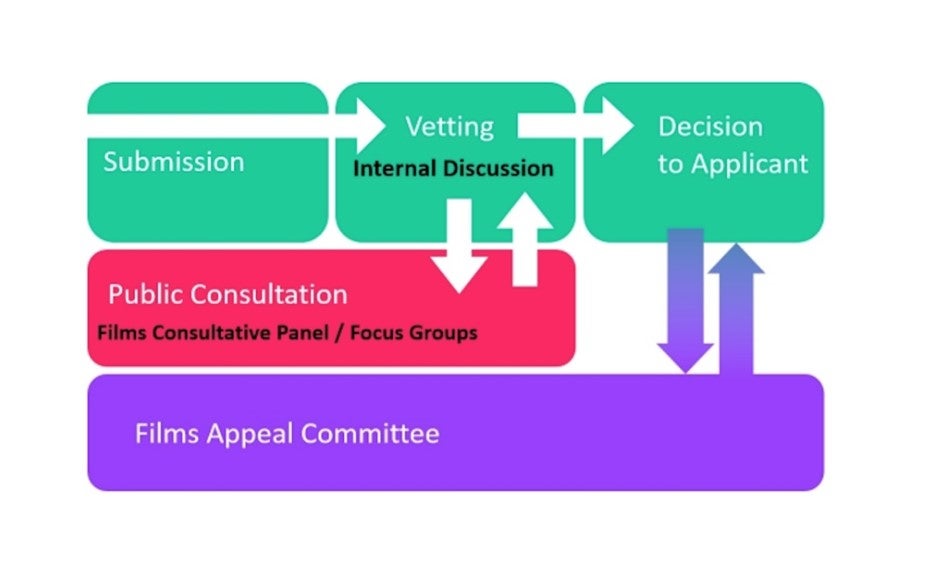

The dominant view of censorship in most contemporary societies, including Singapore, treats it as an external and repressive force originating from the state. In other words, censorship is often simply perceived as an impediment to creativity and expression. This stance, however, glosses over the multiple procedures and operations involved in it. The Board of Film Censors (BFC) also consists of various groups of censors, committee members and panellists with diverse social interests. My article argues that the antagonisms of these processes and roles build uncertainty and contingency into the heart of the film censorship system in Singapore.

As a result, filmmakers often complain that they are plagued by the ambiguity and arbitrariness of classification decisions (Tan, 2007; Lee, 2010). Since many local films are partially funded by the Infocomm Media Development Authority (IMDA), filmmakers are typically subjected to at least two stages of scrutiny during the writing and grant application phases and again when submitting the film for classification. In other words, filmmakers in Singapore have to deal with the censorship system’s ambiguity at multiple levels of their creative process. Censorship therefore becomes an active voice within filmmaking. Seen in this light, both film workers and censors are intimately involved in shaping the intellectual, creative and practical spaces within which Singapore cinema operates, develops and flourishes.

Unfortunately, the veil of secrecy around censorship exacerbates the misunderstanding of censors as mere repressors. I think it would be interesting to consider Singapore cinema from the perspective of the often talked about but relatively understudied censors and their work processes.

‘We have become so racialised that we believe that we are representative of our own communities.’– Censorship and identity politics

As part of its ongoing postcolonial project of imagining itself as a legitimate nation-state, Singapore inherited much of the primordial theories around ‘race’ from its British colonisers. As a result, much of Singaporean life has been governed and framed in racial terms, which also translates into the everyday lives of film censors. As participants in the shaping of Singapore cinema, censors bring their identity baggage to the table.

Take Ken Kwek’s 2012 film Sex.Violence.FamilyValues as an example. The film, which is a collection of three short stories featuring the underbelly of Singapore society, ran into troubles with the censors due to a satirical scene in which an ethnic Chinese director and an Indian actor both made racist remarks about each other. The scene can still be found in the film’s online trailer.

Even though Kwek defended it as racial satire meant to highlight the everyday microaggressions that ethnic minorities face, the scene sparked a lot of nervousness around issues of ‘race’ in Singapore during its censorship processes. These anxieties not only reflect wider societal sensitivities, but ultimately also reveal the political considerations of individual censors themselves.

While censors ought to review and decide films purely in their personal capacity, in practice, it is difficult for them to completely escape the fangs of identity politics. In a public forum organised by Tembusu College in 2013, Hanna Taufiq Siraj, one of the members of the Films’ Consultative Panel, spoke about her experiences classifying the film. Reflecting on her multiple minority identities of being Muslim, Malay and a woman, Hanna admitted that she felt that she had to represent her ‘communities’ when making censorship decisions. Commenting on the ambiguities of ‘community’, Hanna said:

I think all of us… are actually aware of that and conscious of that although… we have become so racialised that we believe that we are representative of our own communities. (Hanna, 2013)

Despite supposedly representing only herself on the panel, Hanna felt the need to make classification judgements based on her imaginations of the ‘communities’ she was considered as belonging to. Tellingly, this perspective was explicitly rebuked by the ethnic Chinese men on the censorship board who were present at the forum.

The burden of representing their ‘communities’ is, of course, unequally distributed across any given social setting and society more broadly. Since minority identities are commonly foregrounded, censors from minority groups tend to feel more responsibility to carry their minority identities into censorship work. So this seemingly objective system of asking censors of different backgrounds to make supposedly detached and unbiased decisions based on their presumed a-political personal opinions actually reproduces the racialization of minorities in practice.

This is not without consequences. In bearing the burden of representing their minority communities, these censors also address and constitute their audiences in specific ways, in this case as racial subjects. This practice then perpetuates a vicious cycle that reinforces the imagination of ethnic audiences as racial, thereby alienating their other subjectivities and reproducing difference along racial lines. In other words, prevailing ideological forces may discipline censorship decisions by policing the ways in which censors imagine whom they are representing.

Censorship and the vocal minority

The intriguing controversies around Ken Kwek’s Sex.Violence.FamilyValues (2012) do not end here. While the Board of Film Censors (BFC) initially granted the film an R21 classification, a negligible number of public complaints about its online trailer led the board to reconsider their initial classification and to later ban the film. This raises the question of the extent a small vocal minority is able to affect and effectively alter censorship decisions.

Underlying the BFC’s responsiveness to public complaints is the Singaporean government’s general brand of conservatism, where policymakers justify their policy decisions by deferring to what they represent as the conservative majority of Singaporean society. Official sensitivity to what they imagine as the conservative majority has implications for the work of the BFC. This not only means that its system is designed to be responsive to statistically insignificant numbers of complaints; it also puts added pressure on censors to err on the side of caution and conservatism.

To the frustration of individual censors, it remains debatable whether or not these small numbers of complaints are representative of the wider community, however understood. By being compelled to act no matter how small the number of complaints, the BFC subjects itself to potential abuses and injects uncertainty and risk into its processes. These inconsistencies, however, are concealed by or attributed to an imagined ‘community’ and its overriding demands. The complaints-based censorship system therefore enables an ideological sleight of hand that replaces the silent majority with the vocal minority.

Imagining the Singaporean silent majority

This ideological sleight of hand raises questions about its potential intangible effects in the long run. Two years after the event, filmmaker Ken Kwek reflected on his experiences of the censorship of his film at a public event.

What’s troubling about it is that ultimately it wasn’t the act of some repressive authoritarian government… It was the public. Because in the end, 20 out of 24 people who were in this public consultative panel brought in to watch the film, voted to ban it… I’m afraid of the average citizen. I’m afraid of the guy next door. And I think that’s a pretty chilling thought. (Kwek, 2015)

I think what Kwek illustrates here are the kinds of perceptual and affective shifts that could result over time due to the censorship system’s inherent uncertainties. Reducing its complexities to a vague and broad entity called ‘the guy next door’ or ‘the public’ arguably expands the anxiety exponentially since the sources of censorship are no longer restricted to governmental authorities but to Singapore society writ large. The unknown ‘public’ not only allows competing imaginations of it to manifest in different circumstances, but also empowers conservative vocal minorities to shape censorship decisions in its name.

This hegemonic, or at least rhetorical, association of the Board of Film Censors (BFC) to ideas about ‘the public’ is, of course, meant to legitimise the censors and their supposed independent judgment, thereby disconnecting them from the political class and its interests. However, this structural feature also produces side effects. If films perform and produce imaginations of the nation (see for instance Edna Lim’s Celluloid Singapore [2018]), the BFC’s high responsiveness to complaints contributes to constructing an imagination of a national people based on a vocal minority conservative in outlook and quick to condemn digressions.

Are the majority of Singaporean audiences indeed conservative or quick to condemn? Beyond simplistic generalisations, it is difficult to determine this in any meaningful way outside of specific contexts. Regardless, Kwek’s remarks reflect how decisions that censors make based on complaints from vocal minorities can reproduce abstract ideas of an imagined conservative ‘public’. While the long-term effects of such a shift in imagination are difficult to measure, it is not hard to see how they work to perpetuate a vicious cycle of paternalistic censorship decisions based on an imagined people in need of continuous protection.

About the Post

This post was written based on the article Imagining film censorship in Singapore: The case of Sex.Violence.FamilyValues (Fong, 2020) published as part of a special issue on Singapore cinema at the journal Asian Cinema. The special issue was co-edited by the author together with Dr Ng How Wee from the University of Westminster in the UK. The article can be found at the author’s personal webpage as well as the journal’s website. I also thank filmmaker Ken Kwek for sharing his perspectives on the matter.