Forgotten narratives: Indigenous Arab-Asian sources of the monsoon history in Malabar

https://doi.org/10.25542/yy93-1j7v

In the past two decades, studies on the Indian Ocean have opened up to scholarly understanding the non-commercial dimensions of the East-West trade routes through the region. Religions, especially Islam, were among the great cultural sources that rippled across the ocean, along with maritime commerce. Many Asian communities have been vital participants in the dynamic trans-regional trade that connected different shores and hinterlands of the ocean. These exchanges were relatively peaceful until the Vasco Da Gama epoch opened at the end of the fifteenth century, when European powers entered the tranquil waters of the Indian Ocean with artillery mounted on ships, playing out ambitious politico-economic strategies.

Even as the Europeans invaded the trans-regional mercantile system and repatriated regional resources back to Europe, mobile Arab diasporas such as Hadramis originating from Yemen remained in Malabar, contributing to the local economy and culture, and in so doing became native. They were indeed native to the maritime circulations of the Indian Ocean, and to individual locales along its rim.

In Malabar, these diasporas and their regional brethren such as Mappilas of Malabar, whom together we can call Arab-Asian societies, have produced valuable sources of history: travelogues, family histories, genealogies, poems of historical and political significance, texts on Sufi scholarly persons and religious texts in a number of Islamic disciplines in various languages such as Arabic, Urdu, Persian, Tamil, Malayalam, Arabic-Malayalam and Arwi (Arabic-Tamil).

The official narratives of western colonial rulers succeeded in investing these societies with a stigma of barbaric, uncivilised and uneducated fanaticism, eclipsing transregional literary and cultural narratives left by these native Arab-Asian communities in textual and oral forms. Historians who mostly relied on colonial sources willy-nilly reflected official narratives, while neglecting the existence of vast materials produced by the local Arab-Asian communities.

For example, Stephen Dale, who wrote on the history of Mappila Muslims of Malabar employing British-Indian police records, almost completely neglects sources written by native societies. Since these native writings were left by scholars as well as leaders who were very close to laymen, and who actively participated in the political fight against the colonial empires, such works will help us understand the other side of stories that had become dominant, almost through sheer force of repetition in official narratives.

The libraries set up by these native Arab-Asian communities at mosques, religious learning centres and their family homes provide alternative archives and sources to understand the history of the region, which has otherwise been unilaterally dictated by colonial officers.

This research note will briefly shed light on two repositories of such native historical sources in Calicut, South India, as examples of archives that can provide us manuscripts, historical materials, and texts written by Arab-Asian and other Malabari communities in various languages. The first of these is a library set up by Hadrami Qadi (Islamic judge) families in Calicut. The second is a private dhow museum that highlights the legacy of dhow manufacturing traditions in the city.

These are among numerous such repositories in the region where I have been working, under the auspices of the Kerala Arab Historical Documentation Initiative (KAHDI), with Professor Engseng Ho as part of the Muhammad Alagil Chair in Arabia Asia Studies at the Asia Research Institute, National University of Singapore.

Hadrami Libraries in the Larger Indian Ocean Networks

The Qadi Library at Chelavur, Calicut was set up by the late Qadi of Calicut, Sayyid Shihab al-Din Imbichi Koya Tangal (d. 1999), who adorned the position of Qadi for more than fifty years, beginning in 1948. Sayyid Shihab al-Din belonged to a Hadrami Sayyid family that emigrated from Hadramawt in Yemen to Malabar from the eighteenth century onwards. As members of Sayyid families, they claim to be descendants of the Prophet Muhammad. Their emigrations to Malabar were part of the long historical movements of Hadrami Sayyids across the Indian Ocean. From the eighteenth century onwards, these families settled in the Malabar region in large numbers.

As Hadrami Sayyids settled, they became well regarded in religious, social and political circles in host societies, and many of them succeeded in becoming religious and political leaders in these regions. In Malabar, Hadrami immigrants such as Shaykh al-Jufri of Calicut (d. 1808), Sayyid Alawi of Mamburam (d. 1844), Sayyid Ali al-Hadrami al-Shihab (d. 1820) and many others actively pursued and led notable religious and political projects. With the fall of the Muslim rulers of Mysore in the 1790s after their defeat by the British, Hadramis came to fill the vacuum in Muslim political and religious leadership across the region.

A case in point is the seat of Qadi of Calicut, a position adorned by the aforementioned Hadrami Sayyid Imbichikoya Tangal and other Hadramis since the nineteenth century, which dates back to at least the fifteenth century, if not before. The collections he inherited from previous Qadis consist of very precious manuscripts written centuries earlier, at least since the office of Qadi was established in Calicut.

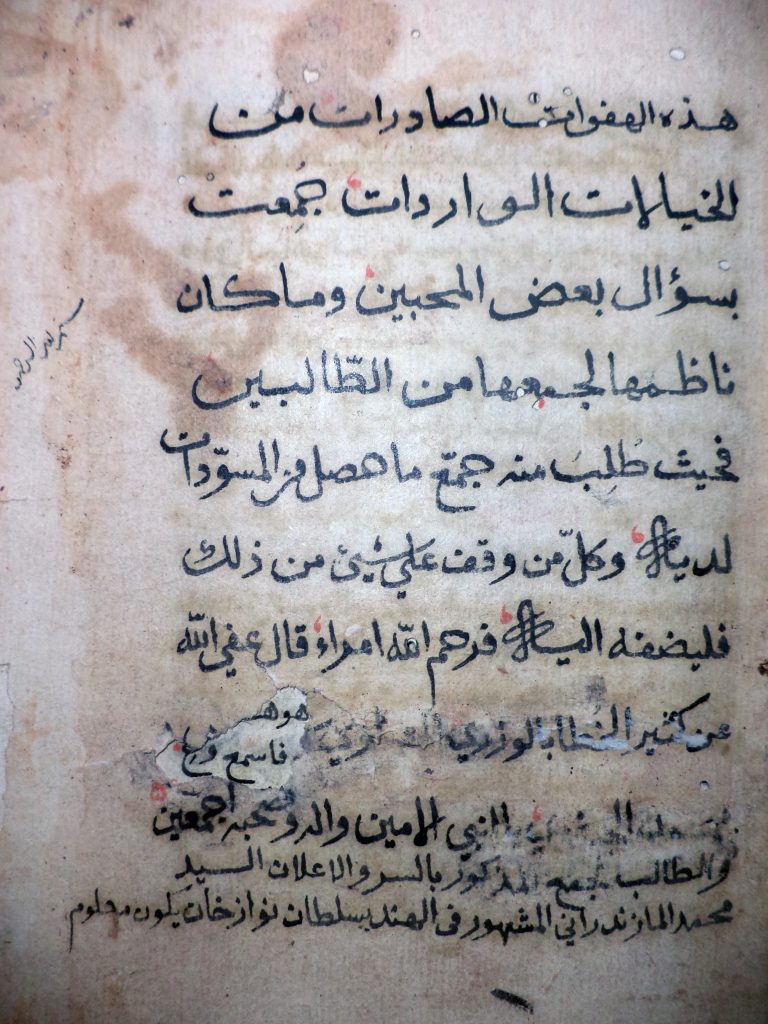

The library of the late Qadi Sayyid Shihab al-Din at his son Abdullakoya’s home in Calicut is one among the many preserved by members of the Hadrami Qadi families in the region. The library of Qadi Shihab al-Din consists of a number of precious manuscripts written by early Hadrami immigrants, as well as by earlier Qadis.

For example, an autobiographic memoir by one of the early immigrant Hadrami scholars of the eighteenth century, the eminent Shaykh al-Jufri, is titled al-Hafawat al-Sadirat. For those interested in the history of eighteenth and nineteenth century Malabar, al-Jufri’s Hafawat is a precious text, as it explains many autobiographical notes and poems he authored, and reflects personal stands he took on contemporary socio-political developments.

These include the anti-British wars led by Mysore rulers such as the famed Tipu Sultan, and reveal Arab-Asian support for Tipu and his administrative centralisation in Malabar. Another manuscript by al-Jufri, Kawkab, details the place of Malabar Hadramis within the larger networks of Hadrami communities in the Indian Ocean and elsewhere. Later generations of Arab-Asian communities in Malabar also left valuable writings.

Such works written by Arab-Asian communities help provide alternative perspectives on the region, which have not received adequate scholarly attention. Important among them are collections left by Qadis and scholars, their memoirs, travelogues, correspondences and scholarly texts. At the Qadi library in Calicut we see important Sufi works, litanies and political treatises written against the colonial powers in Malabar, in manuscript and printed form. These works are potent sources for future revisionist histories of the region, tying political developments to socio-ritual events through common subaltern folk narratives.

Hadrami Sayyid leaders such as Sayyid Alawi and Sayyid Fadl (d. 1900) led lower sections of local society in intense resistance to the consolidation of British rule in South India after the defeat of Tipu Sultan in 1792 (and the subsequent global defeat of the French in 1815, with whom Tipu was allied). Among the manuscripts and printed texts available in the library are writings by significant Hadrami figures such as Sayyid Fadl, who, after leading anti-colonial resistance in Malabar, had subsequent roles such as Ottoman governor in southern Arabia and advisor to Sultan Abdul Hamid II in Istanbul. Rare treatises of his political views advocating for pan-Islamic leadership under the Ottomans are found in this library.

Likewise, many Sufi litanies composed by early immigrants and autobiographical sketches of renowned Hadrami figures in the region are noteworthy items in the manuscript collections of the library. Since the owners of the library were the Qadis of Calicut, important papers and records from the Qadi House document marriages between foreign Arabs and local women, and provide rare sources for researching the longue durée processes of multicultural accommodation that have shaped Malabar society so profoundly.

Many such library collections in Malabar are rich with precious manuscripts written by early Arab immigrants, local scholars and Qadis in various genres such as poems, scholarly proses, Sufi litanies, talismanic texts and so on. Being influential persons who worked closely with local people as religious judges as well as practitioners of talismanic healing among laymen, their works are highly significant because they provide alternate narratives that will enable future generations of researchers to understand Malabar history and society in ways different from the dominant historiography established by colonial officials of the British Empire.

A Dhow Museum in Calicut

At the edge of South Beach in Calicut, which had historically been a buzzing port city for the trade of Malabar spices and timber, a centre for preserving the history of the dhow trade has been set up by Mr Hashim, the Managing Director of Haji PI Ahmed Koya Boat Builders. The Dhow Museum is located in his refurbished office attached to the old warehouse of Haji PI Ahmed Co. for manufacturing dhows (locally called Uru). The family business of dhow building was founded by Hashim’s grandfather Kamantakath Kunhammad Koya in the 1880s. The company manufactured huge dhows for clients mostly from the Persian Gulf. In order to preserve the history of dhow building, which has recently plunged into a deep crisis mainly due to the scarcity of quality timber, Hashim converted a part of their old office into a Dhow Museum that exhibits the historical transregional connections of Malabar’s maritime dhow business and timber trade.

The museum, which is open to visitors and researchers, contains invaluable historical records, accounting books, assets, and other materials concerning dhow manufacturing and trading, mostly related to the family firm. The records relating to a large goods dhow called Bhoom, built in 1916 for the al-Ma’rafi family of Kuwait, provide interesting historical information regarding the dhow trade with Arabia before the oil boom.

Although most are twentieth century records, a good collection of original accounting books is available for researchers, along with a number of letters of correspondence with Arab clients. These contain a wealth of information on maritime trade crossing the Indian Ocean. Records of telegraphic money transfers from Kuwait, Oman and Bahrain are displayed along with pictures of various dhows built by the firm, Nakhudas (Captains) and owners of ship building companies. Among the dhows recently built by the company were a number of vessels purchased by affluent persons from Qatar, such as Khalifa al-Itmi. Replicas of a variety of dhows, vessels and Zambuks are on display, along with related materials.

Individual efforts to preserve the histories of maritime timber and dhow trades such as Hashim’s Dhow Museum are commendable. They provide exciting gateways into hitherto unknown materials related to the history of inter-Asian maritime trade and cultural relations that kept societies of these regions connected. These two centres in Malabar that preserve native Arab-Asian manuscripts and artefacts are very rich sources for decolonising our understanding of the socio-religious and political histories of Malabar.

Hidden in these rich troves are interesting scholarly and lay contributions made by native Malabaris, members of the Arab-Asian mobile societies who became Malabaris, and the humdrum traders among them. These records enable scholars to mount the serious challenges to establishing narratives that have often been reiterated by official colonial historians and their nationalist inheritors, putting blinders on the agency of native Arab-Asian societies, including the Mappilas of Malabar.

The breadth and scope of writings and objects left by these communities, preserved in private libraries and museums in the region, call for—and enable—a thoroughgoing re-examination of the processes in which commercial, religious and cultural threads became intertwined through long-distance trade routes and maritime communities. Malabar society has been profoundly shaped by such interactions over centuries with peoples and places from far away, as have most societies around the Indian Ocean. The collections we have been diving into in Malabar have turned out to be like so many sunken treasure ships lying at the bottom of one of its heralded ports.

The views expressed in this forum are those of the individual authors and do not represent the views of the Asia Research Institute, National University of Singapore, or the institutions to which the authors are attached.

Abdul Jaleel P.K.M. is currently a researcher under the KAHDI project associated with the Muhammad Alagil Chair at the Asia Research Institute, National University of Singapore. He taught West Asian Studies at the University of Kerala and was a visiting fellow at Berlin Graduate School Muslim Cultures and Societies, Free University, Berlin. jalijnu@gmail.com