Global Gurkhas: Reflections on migration, soldiering and development in Nepal

https://doi.org/10.25542/he1t-9q95

Over the years, I have travelled to Nepal several times to carry out fieldwork and interview repatriated Gurkha families. Upon their retirement from the British Army, Singapore Police Force, or the Gurkha Reserve Unit in Brunei, a significant number of these families have opted to relocate from their villages. While I have explored these urban areas, I was always keen to venture deeper into the rural villages and ancestral homes of Gurkha families. So, in November 2022, together with my partner, we planned a short trek to Poon Hill in the Annapurna region of western Nepal.

This picturesque area is particularly significant as it is one of the origins of Gurkha families. By and large, the Gurkha community, traditionally made up of ethnic groups like Gurungs, Magars, Rais, and Limbus are considered as "martial races" in the context of British colonial knowledge production, and are dispersed across both the western and eastern hill regions of Nepal. During my exploration of the Annapurna range, I had the opportunity of encountering Magar and Gurung villages. Trekking through the majestic mountains in this region not only provided me with a grassroots understanding of Nepal's historical ties to Southeast Asia but also offered valuable insights into the impact of repatriation and remittances on the political economy of local tourism, among others.

Inter-regional soldiering ties and transnational mobility link Nepal to Southeast Asia. In the aftermath of India’s independence in 1948, the ten battalions of Nepali Gurkhas that had long served the British Raj were reconstituted. While six battalions remained in India, four were transferred to Britain and subsequently, the “regimental home” of the “British Gurkhas”—as they came to be known—moved to Malaya. From the late 1940s till the early 1970s, British Gurkhas were actively involved in the Malayan Emergency (1948–1960), Brunei Rebellion (1962) and Konfrontasi (1963–1966). In the past, British Gurkhas served for 15 years before being repatriated. The same period also witnessed the development of Gurkhas as a distinct policing unit in both Malaya and Singapore.

In Singapore, the Gurkha Contingent within the Singapore Police Force and under the Ministry of Home Affairs was established on 9 April 1949. The Gurkha Contingent recently commemorated their Diamond Jubilee on 9th April 2024, and as an elite policing unit, they continue to have a vital presence in the country’s internal security as a “neutral force”. In 1962, the establishment of a British Gurkha garrison in Brunei was prompted by a local revolt and forged another notable transnational historical connection to Southeast Asia. In Singapore and Brunei, Gurkha families lack citizenship rights and upon the completion of their contractual service, they are repatriated to Nepal. Owing to the extension of citizenship and settlement rights in the context of the United Kingdom and the renegotiation of migration strategies and pathways, Gurkha families are now dispersed globally, spanning locations such as the United Kingdom and Hong Kong to Australia and the United States.

Poon Hill, the picturesque hill station, was founded by the late Major Tek Bahadur Pun, a local and former Gurkha. It was intriguing to learn that the viewing tower at Poon Hill is dedicated to him in recognition of his pivotal role in initiating the creation of the trail leading to its summit. The trail and the construction of a viewing tower at the summit allows trekkers to relish the breathtaking sunrise and sunset vistas of the Himalayan range and has contributed significantly to its popularity among trekkers from around the globe, thus boosting local tourism.

Apart from infrastructure development, many Gurkha families upon retirement and repatriation have spearheaded initiatives aimed at uplifting their communities such as providing educational opportunities and initiating various social projects. These endeavours are a testament to the impact of migrant earnings in facilitating community activism and social engagement.

Tourism plays a major role in the economic landscape of Nepal’s trekking regions. During a lunch break at one of the lodges, the owner shared that he used to be a lahure (local vernacular used to refer to ‘Gurkha’); now upon repatriation, he runs a lodge. This anecdote is emblematic of a broader trend, as a significant number of tea houses and trekking lodges in the area are overseen by families with a Gurkha connection, formerly serving in countries such as Singapore, Hong Kong, Brunei, or the United Kingdom.

Their transition from soldiering into entrepreneurship underscores the vital link between transnational soldiering, local tourism and the socio-economic transformation of the village community. From casual conversations with locals as my journey unfolded, an interesting aspect emerged: a considerable number of tea houses, owned by Gurkhas, are often not actively operated by them as most of them have since re-migrated elsewhere. In other words, although they have invested in establishing some of these lodges, the day-to-day operations, management, cooking and catering to tourists are predominantly handled by other immediate or extended family members.

Notably, a significant portion of these roles are fulfilled by womenfolk, adding a noteworthy gendered dimension to the dynamics of ownership and operation within these establishments. These teahouses signify how soldiering generates opportunities in the long-term as individuals invest in initiatives that not only sustain local economies but also contribute to the livelihoods of women in the region.

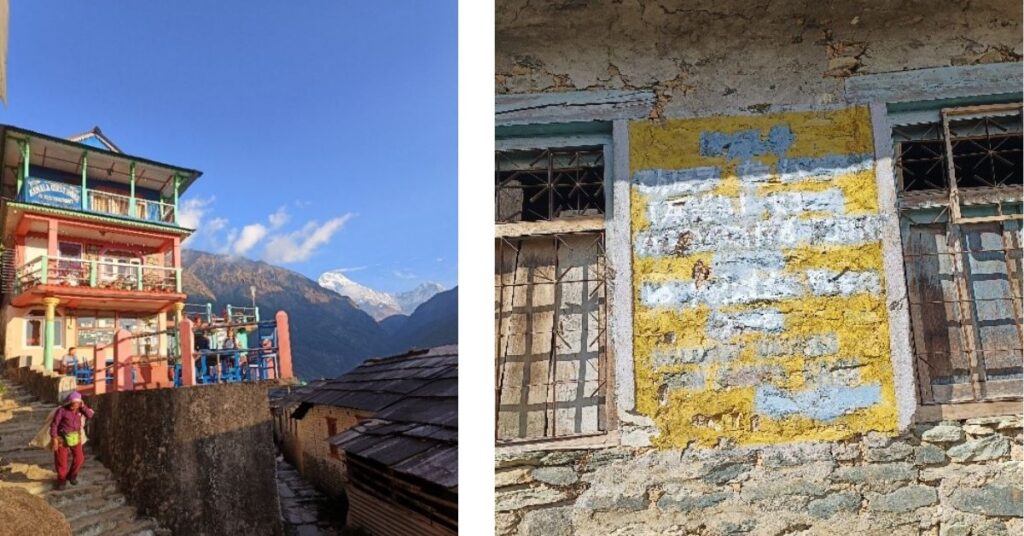

Descending from Poon Hill along the Ghorepani-Ghandruk trek, our path led us through quaint Gurung villages. Along the way, a weathered sign on a stone wall caught my attention, bearing the words in Malay. Sensing a potential link to Singapore or Malaysia, I cautiously approached the gates of the sprawling cottage and introduced myself to a lady seated on a stone bench. In conversation, she revealed that she had spent her childhood in Singapore in the 1970s as her father served in the Singapore Police Force as a Gurkha.

She recounted her educational years at Cedar Girls’ School and the family’s subsequent repatriation to Nepal. Her father had established the lodge after repatriation, and although he had since passed away, her brother (who also spent his formative years in Singapore) and sister-in-law continue to run the business. In a village in Nepal, far removed and distant from Singapore, a remarkable narrative of soldiering emerges against the backdrop of migration and colonial legacies. The historical ties between these families and our city-state persists and continues to hold significance.

As we descended further along our path, I chanced upon a recently established shrine. Adjacent to the staircase leading to the shrine, a distinguished black plaque proudly displayed the names of Gurkha ex-servicemen donors who had served in various countries. Their generous contributions played a pivotal role in the creation and development of this sacred space atop the hill.

Over generations, serving and ex-Gurkha families have played a dynamic role in the rural life of Nepal, engaging in infrastructure development, providing essential social services in education and community welfare, financing religious shrines, and contributing to the entrepreneurial landscape through the operation of tea houses and lodges for a thriving tourism industry. This multifaceted involvement has significantly influenced the political economy and grassroots development, exemplifying the profound impact of transnational soldiering on socio-economic change at the local level.

The views expressed in this forum are those of the individual authors and do not represent the views of the Asia Research Institute, National University of Singapore, or the institutions to which the authors are attached.

Dr Hema Kiruppalini is a historian whose research is focused on trans-regional migration within the context of South Asia, particularly the Himalayas and Southeast Asia. Her work explores race, coloniality, gender, soldiering, and social histories. Her doctoral dissertation and publications, which reconstruct the social worlds and transnational history of Nepali Gurkha families in post-war Asia, has received several scholarly accolades such as the BNAC PhD Dissertation Prize and the Craig A. Lockard Prize. At ARI, she works on the project Archiving the Underclasses: Knowledge, Law, and Everyday Agency in Modern Southeast Asia.