Hero There, Villain Here: Memory Friction in Indonesia and Singapore

A Hero’s Name, A Past Wound

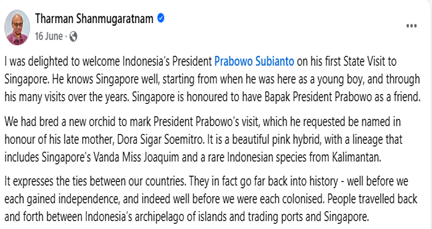

When Indonesian President Prabowo Subianto visited Singapore in June 2025 as guest of honour for the republic’s 60th National Day celebrations, the atmosphere was exceptionally friendly. He praised Singapore as a model and remarked that Indonesia would, " copy Singapore's successful policies with pride,". The relationship between Indonesia and Singapore has long oscillated between pragmatic cooperation and historical discomfort. At its heart lies the question of memory how both nations remember their shared past.

Figure 1: Singapore President Tharman Shanmugaratnam presents an orchid named after Prabowo Subianto’s late mother during the state visit, June 2025 (Source: Tharman Shanmugaratnam, Facebook, 16 June 2025.)

A decade earlier in 2014, the Indonesian Navy christened two new frigates, the KRI Usman-Harun and KRI John Lie. What Jakarta considered a regular tribute to its national heroes angered, surprised and disturbed Singapore, provoking unease across the Strait. To Singapore, honouring the marines Usman bin Haji Muhammad Ali (1943–1968) and Harun Said (1947–1968), the men executed for the 1965 MacDonald House bombing that killed three civilians, reopening an old wound. To Indonesia, they remained soldiers who had sacrificed their lives for the republic.

In the same year, Indonesia also launched the KRI John Lie, named after Rear Admiral (Res.) Jahja Daniel Dharma (1911–1988), better known as John Lie, the “Ghost of the Malacca Strait.” During the independence struggle, Lie operated from Singapore, smuggling rubber out and weapons in to break the Dutch blockade. His wartime missions, daring and secretive, made him a national legend in Indonesia but a morally ambiguous figure through colonial eyes, a “Chinese smuggler” who defied maritime law. While his hero designation in 2009 attracted little international reaction, the later decision of a warship after him revived questions about how Indonesia decides whose actions deserve to be called heroism.

These episodes expose a recurring friction between commemoration and diplomacy. For Indonesia, naming warships after Usman, Harun, and John Lie celebrates sacrifice, courage, and loyalty to the republic. For Singapore, the same gestures evoke violence, disruption, and moral discomfort. The tension between “my hero is your enemy” is not simply a matter of perspective; it reflects how colonial histories, post-independence anxieties, and state-sponsored memories continue to shape Southeast Asia’s present.

The Making of a National Hero in Indonesia

In Indonesia, pahlawan nasional (literally national heroes) are state-sanctioned figures crafted to unify a diverse nation. The recognition is formalised through the National Hero Program, inspired by President Sukarno’s famous declaration: “Bangsa yang besar adalah bangsa yang menghormati jasa para pahlawannya”—A great nation is one that honours its heroes.

The very word pahlawan carries martial roots, drawn from Persian and Sanskrit terms for “wrestler” and “mighty man.” From its inception in the 1950s, the programme framed heroism as resistance to foreign domination. This was more than remembrance and designation, it was a nation-building project. For a new republic emerging from colonial rule, a shared narrative of struggle against a common enemy offered a powerful means of cohesion.

Over time, the programme did more than commemorate the past. It defined the moral ideals that the state wished to project. The archetypal hero was imagined as, militarised, and self-sacrificing—someone who defended the republic with courage and discipline. The canon became a mirror of Indonesia’s founding ethos, one that elevated loyalty and endurance above all else. This logic helps explain why figures such as Usman, Harun, and John Lie occupy revered places in Indonesia’s national story. Each embodied the spirit of defiance against external control and paid a heavy price for it. Yet this same framework, when viewed from abroad, reveals its limits. Acts celebrated as patriotic sacrifice in Indonesia may appear as aggression or act of terror in another. For nations as closely intertwined as Indonesia and Singapore, such divergent readings of the past turn shared history into into a source of recurring friction.

Usman and Harun: The Legacy of the MacDonald House Bombing

The story of Harun bin Said and Usman bin Haji Mohamed Ali remains one of the most charged memories in Southeast Asian history. It unfolds during Konfrontasi (Confrontation), an undeclared war waged by Indonesia from 1963 to 1966 to oppose the formation of the Federation of Malaysia, which at the time included Singapore. Historian J.A.C. Mackie described the conflict as an "enigmatic affair, less than a war but something more than a mere diplomatic dispute." Sparked by the 1962 Brunei Revolt, Indonesia's opposition to the formation of Malaysia involved campaign of propaganda and "low-level military incursions" against the new federation, of which Singapore was then a part.

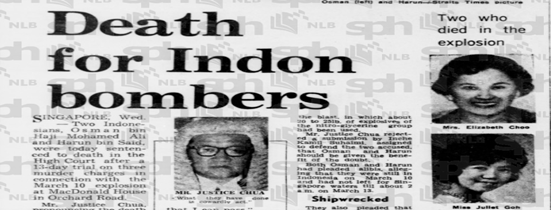

On 10 March 1965, this conflict struck the heart of civilian Singapore. Two Indonesian marines, Harun and Usman, disguised in plain clothes, planted a powerful bomb at MacDonald House on bustling Orchard Road. The attack killed two bank employees, Elizabeth Suzie Choo and Juliet Goh, and a driver, Mohammed Ghouse, and injured 33 others.

Figure 2: Aftermath of the 1965 MacDonald House bombing in Singapore. Photo: Channel NewsAsia (TODAY)

After their capture, they were tried for murder under Singaporean law and executed on 17 October 1968. The event became a cornerstone of Singapore’s national narrative, a traumatic lesson in the nation’s vulnerability that continues to justify its unwavering focus on security.

Figure 3: Coverage of the MacDonald House bombing trial in The Straits Times, 21 October 1965. (Source National Library Board, Singapore.)

Indonesia remembers the same event through a profoundly different lens. In Jakarta’s view, Usman and Harun were soldiers carrying out orders in a legitimate military campaign. Their execution was seen as a moral injustice, an affront to sovereignty. When their bodies were returned to Indonesia, they were welcomed by a grand public procession and laid to rest at the Kalibata Heroes’ Cemetery in Jakarta with full military honours. Posthumously declared Pahlawan Nasional (National Heroes) in 1968, they are remembered as martyrs who sacrificed their lives for the state

John Lie (1911–1988): A Friction of Values

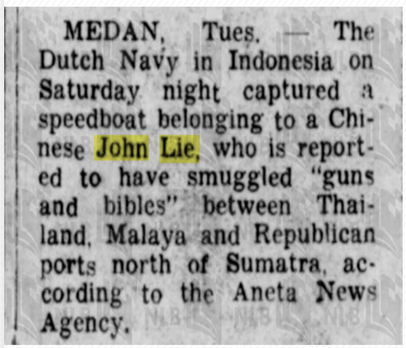

The friction of historical memory between Indonesia and Singapore is not limited to acts of direct violence. The legacy of John Lie reveals a different kind of tension that rooted in conflicting national values and colonial-era perspectives. During Indonesia’s independence struggle (1945–1949), John Lie, who was later renamed Jahja Daniel Dharma under the Suharto regime’s assimilation policy, was a key figure in the naval resistance against the returning Dutch. During Indonesia’s independence struggle (1945–1949), John Lie was a key figure in the naval resistance against the returning Dutch. Operating primarily out of Singapore, he commanded small, fast vessels that slipped through the Dutch naval blockade, smuggling rubber out and weapons in to sustain the fledgling republic. His missions earned him the nickname “Hantu Selat Malaka” (the Ghost of the Malacca Strait), a testament to his agility and audacity.

Newspapers of the time such as The Straits Times and Malaya Tribune portrayed Liet as a “Chinese smuggler”. This colonial era framing of his revolutionary activities as criminal is the root of the modern friction.

Figure 4: DUTCH CATCH SMUGGLERS The Straits Times, 5 October 1949, Page 1; Figure 5 'GUNS AND BIBLES' SPEEDBOAT CAPTURED Malaya Tribune, 5 October 1949, Page 1

This divergence continues to resonate in his modern commemoration. For Indonesia Lie's 2009 designation as a National Hero was a powerful statement of inclusive nation-building, honouring the sole ethnic Chinese Indonesian in a pantheon from 1959 to this date. When the Indonesian Navy also commissioned the KRI John Lie in 2014, it was a celebration of this multicultural patriotism. For the official veneration of a figure for acts of crime presents a challenge. It creates an uncomfortable friction for a nation whose identity and prosperity are built on the very principles of maritime law and commercial order that Lie’s revolutionary activities defied.

When Old Wounds Reopen: The 2014 Ship-Naming Incident

For decades, the two memories of Usman and Harun existed in parallel: heroes in Indonesia, terrorists in Singapore. This dormant tension erupted in February 2014, when two naval commemorations brought the issue to the fore.

The first, and more dramatic, was the announcement that a new frigate would be named KRI Usman-Harun. The reaction from Singapore was immediate and sharp. Then-Foreign Minister K. Shanmugam condemned the decision as a "setback" that would "re-open old wounds." In a concrete show of displeasure, Singapore barred the frigate from its ports and cancelled some planned joint military activities. For Singapore, naming a warship after men convicted of killing its citizens was a painful and insensitive glorification of terrorism. Similarly, the commissioning of the KRI John Lie in the same period highlighted the other side of this friction. While there was no formal diplomatic protest, it’s the act of celebrating a figure known for revolutionary smuggling.

Indonesia’s defence was consistent. Military and government leaders insisted that naming the ship was a sovereign right and a long-standing tradition of honouring national heroes. Indonesia’s defence, on principle, was firm. Military and government leaders insisted the naming of both ships was a sovereign right. However, in an attempt to manage the diplomatic fallout from the KRI Usman-Harun, Indonesian Armed Forces chief General Moeldoko later offered a carefully worded apology. While stating the name would not be changed, he apologized for the unrest the incident had caused, clarifying there was no ill intention whatsoever, showing the apology for the reaction, not the act.

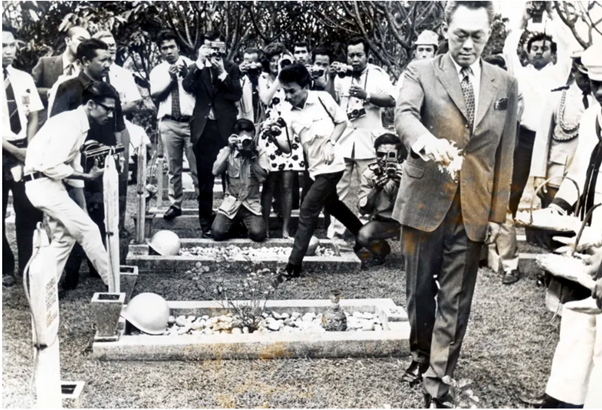

Figure 6: Singapore Prime Minister Lee Kuan Yew scattering flowers at the graves of Usman bin Haji Mohamed Ali and Harun bin Said at the Kalibata Heroes’ Cemetery in Jakarta, 28 May 1973. (Photo: Kompas / Pat Hendranto.)

These contested memories matter because they shape contemporary relations. After the marines' execution in 1968, repairing Indonesia-Singapore ties required careful choreography. Lee Kuan Yew, made breakthrough in his visit to Indonesia in 1973. Lee visited the Kalibata Heroes’ Cemetery. After laying a wreath for Indonesia’s fallen generals, he scattered flowers on the graves of Usman and Harun. Lee stated that this act was essential to addressing "Javanese beliefs in souls and clear conscience". It was a pragmatic acknowledgment of Indonesia’s narrative of martyrdom without requiring Singapore to repudiate its own. It showed that reconciliation did not demand consensus on the past, only a mutual willingness to navigate contested truths for the sake of a stable future.

The stories of John Lie, Harun Said, and Usman Ali reveal that heroism, when viewed through the lens of nationalism, is never universal. It is shaped by local histories, colonial legacies, and the moral boundaries of each nation-state. Indonesia’s post-colonial identity was forged in a revolutionary struggle, creating a heroic framework where resistance against foreign powers became a primary virtue. This framework is a complex inheritance, because these historical narratives are continually repurposed to serve the needs of the present, shaping national identity and, at times, creating friction with neighbours.

For two nations as deeply intertwined as Indonesia and Singapore, navigating this fraught history is not about forcing one side to adopt the other's narrative. Instead, it requires a clear-eyed acknowledgment that these memories are real and deeply held on both shores. Ultimately, while a nation’s right to define its heroes is a sovereign one, the consequences of that choice are shared. Effective diplomacy requires a form of memory literacy, an ability to understand that the historical truths a neighbour holds dear may be fundamentally different from one’s own that needs to manage with care. This forward-looking diplomacy is active and ongoing. As President Prabowo Subianto’s state visit to Singapore in June 2024 affirmed, past differences have been put aside and the two nations "are like brothers". The mirrors across the sea will continue to reflect these inversions, heroes here, villains there. The test for both nations is whether they can acknowledge them without letting the reversed images obscure a shared future.

The views expressed in this forum are those of the individual authors and do not represent the views of the Asia Research Institute, National University of Singapore, or the institutions to which the authors are attached.

Dr Myra Mentari Abubakar commenced her NUS Fellowship with the Asian Urbanisms Cluster with effect from 9 December 2024.

She completed her PhD in 2024 at The Australian National University and is currently engaged in extensive research on the hero phenomenon across Indonesia and Southeast Asia. Affiliated with the International Centre for Aceh and Indian Ocean Studies (ICAIOS) in Aceh, her research primarily focuses on gender and cultural history with an emphasis on Indonesia. At ARI, Dr Myra will explore the complex dynamics of memory and heritage in urban settings. She seeks to shed fresh light on cultural and historical framework by tracing how sites of hero legacy and gendered narratives shape public spaces and collective memory within urban landscapes.

https://doi.org/10.25542/6y35-nhq