In Conversation with Dr Myra Mentari Abubakar

Figure 1: Myra led and performed Acehnese Ratoh Duek dance, Australia Indonesia Business Council 2018, Australia Parliament House Canberra.

You've worked and studied across Indonesia, Australia, and beyond. How have these different academic and cultural environments shaped your research and teaching?

Movement across borders has always been at the heart of my work, not only translating between languages and cultures but also learning to navigate different worlds. I was born and raised in Aceh, the westernmost province of Indonesia, known for its long history of armed conflict, the devastation of the 2004 tsunami, and as the only province with the formal implementation of shariah law. My education was shaped as much by choice as by circumstance; some moves were deliberate, while others were driven by conflict and disaster. At twelve, I left home in Aceh Timur to attend Dayah Bustanul Ulum and Madrasah Ulumul Quran in Langsa, where I spent six formative years immersed in Islamic and general education. While many of my peers pursued further study at Islamic universities or in the Middle East, I chose a rather different path, completing a Bachelor of Literature at the State University of Medan, where I studied applied linguistics and literary studies.

That early shift, from a gender-segregated classroom in a predominantly Muslim province to a secular campus where Muslims were a minority, was my first major academic transition. From there, my journey continued through places including Jakarta, Canberra, Leiden, and now Singapore. Each place was not just a stop along the way but a vantage point that shaped the questions I ask, the way I teach, and how I learn to read context.

Australia was especially foundational. A Master of Education at the University of Canberra (UC) and a PhD in Gender, Media, and Cultural Studies at the Australian National University (ANU) gave me the critical distance to examine Indonesian history with fresh eyes. Guided by an interdisciplinary supervisory panel, I situated my PhD on a study of female heroism in Indonesia, focusing on Cut Nyak Din (or Tjoet Nja Dhien, 1848-1908), an Indonesian female national hero from Aceh, at the intersections of history, anthropology, gender theory, and cultural studies. Tracing her afterlives across Dutch colonial archives, Acehnese oral traditions, and Indonesian state narratives taught me that archives are never neutral repositories, but curated voices entangled with power.

Alongside research, teaching and community engagement have always grounded me. In Canberra, I taught Bahasa Indonesia to high school and university students, defence personnel, and diplomats preparing for postings in Indonesia. At the same time, I coordinated and performed Acehnese dance at cultural festivals and served as president of the ANU Muslim Students Association, representing a global student body. These experiences taught me to approach both teaching and research as practices of cross-cultural dialogue.

Figure 2: Myra conducting a cultural showcase at the Indonesia Fair in Canberra, Australia.

Figure 2: Myra conducting a cultural showcase at the Indonesia Fair in Canberra, Australia.

Today, at ARI, I carry this cross-cultural lens into my projects. Within the Asian Urbanisms cluster, I examine gender, heritage, and memory politics through the lens of heroism drawing from sites, texts, and counter-archives to recover women’s stories that have often been excluded from official narratives. In that sense, movement remains my method: connecting places, materials, and communities to tell fuller and more accountable histories.

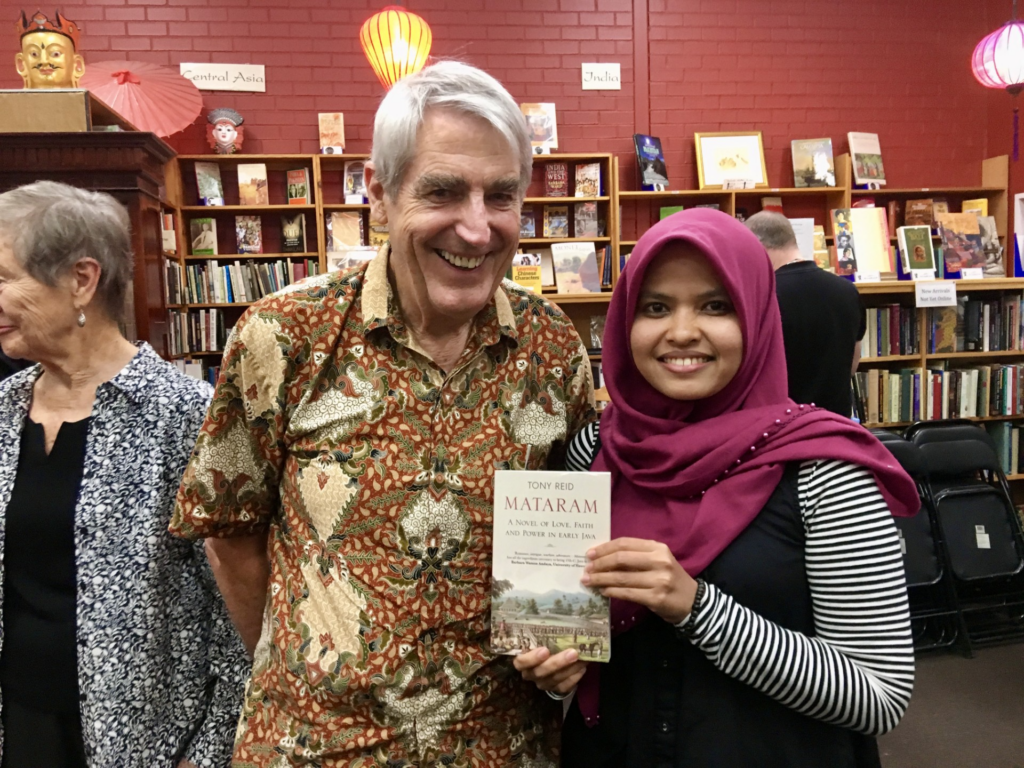

The late Emeritus Professor Anthony Reid was your HDR supervisor at ANU. Can you tell us a little about your experience?

With his recent passing in June 2025, I can understand why this question carries particular weight. Anthony Reid or Pak Tony, as many of us affectionately called him, was one of the most formative figures in my academic journey. His loss is felt deeply at ARI and across the global Southeast Asian studies community and beyond. The last time I spoke to him was on Zoom in April. I jokingly said, “Hi Pak, Greetings from ARI, the Anthony Reid Institute,” and he laughed. I never imagined that would be our final conversation.

Figure 3: With Professor Tony Reid in 2023. Photo: The Australian National University.

We first crossed paths at a seminar by the ANU Indonesian project we were both attending. I was hoping to begin my PhD then. Despite his giant name, Tony’s humility made him approachable, and after a brief conversation he agreed to supervise my project. Though already retired, he took me on as his last PhD student at a time when few specialists on Aceh remained at ANU. That was an act of generosity that changed the course of my life. He then assembled an interdisciplinary panel: Shameem Black, Ronit Ricci, and Kathryn Robinson alongside himself, that allowed me to approach female heroism in Indonesia from multiple angles.

Tony had a way of offering you a map without dictating the route. He guided with clarity, kindness, and trust. For someone like me, an average student from a modest background in Aceh, his belief in my work gave me confidence I didn’t yet have in myself. When harsh self critique slowed me down, he reminded me that scholarship is not a sprint but a long journey. During the long, uncertain years of the pandemic in Canberra, when I could not return home for more than two years, Tony was my first point of contact. He and Helen Reid, who felt like a mother to so many of his students, were always there. He never failed to answer my calls, listening without judgement and encouraging me to take one step at a time when I felt overwhelmed.

What truly defined him was a generosity that went far beyond his official role. I would travel to a new country for a conference or fieldwork and later discover he had contacted colleagues ahead of my arrival, ensuring I would have a network of support. I once moderated his talk, and the first thing he did after being introduced was to introduce me: “Meet Myra, my PhD student…” always making space for others, even in his own spotlight.

In 2023, he was named “Supervisor of the Month” at ANU, an award he humbly downplayed as undeserved, calling it simply a farewell gesture after fifty-five years of supervision. He described supervision as a “rare privilege,” and that was precisely how he treated it. His passing is a great loss, but he left behind a powerful model for what a scholar and mentor should be. His influence continues in the way I try to approach my own work: with rigor, but also with kindness, a commitment to community, and a belief in the power of generosity.

You were part of the AGSF19 cohort at ARI in 2024. How was your experience, and how have you found coming back to ARI as an NUS Fellow?

Figure 4: Myra with fellow participants of the 19th Singapore Graduate Forum on Southeast Asian Studies (AGSF19) at the Asia Research Institute, NUS (June 2024)

The 19th Singapore Graduate Forum on Southeast Asian Studies (AGSF19) in 2024 was my front door into ARI—and the beginning of what has since become a scholarly home. At the time, I had just completed my PhD and was still finding my footing. Having applied more than once before being selected, finally joining the cohort felt especially meaningful. The forum brought together early-career scholars from across the region and beyond, creating a generous and interdisciplinary space to test ideas and receive constructive feedback. Presenting my paper—From Dutch Pages to Indonesian Hearts, on how colonial writings helped shape the image of Acehnese heroine Cut Nyak Din—showed me how my work could resonate outside the boundaries of Indonesian studies. It gave me a first glimpse of the intellectual energy of the institute, and the kind of community I hoped to join.

By then, I had already been at NUS since late 2023 on an IARU fellowship in the Department of History, hosted by Professor Tim Barnard. Now, as an Academic Fellow at ARI under the mentorship of Professor Tim Bunnell, I’ve had the wonderful experience of learning from two “Tims” with complementary approaches to Southeast Asian studies. Returning to ARI in this new role has felt like a true homecoming—an opportunity to build on earlier connections and contribute more fully to its vibrant intellectual life.

I also appreciate how thoughtfully ARI welcomes newcomers, the ARI buddy system, the “In the Beginning” talk, and the genuine interest colleagues show in hearing your story. Having spent eight years in Australia before moving to Singapore, these gestures made me feel at home, and I hope to pay it forward by supporting others who arrive after me.

And on a lighter note, my mother’s name is Ari, and she named me Mentari with ARI embedded in it. I like to think that is why ARI feels close to my heart. 😄

Your PhD focused on Cut Nyak Din and the representation of female heroism in Indonesia. What drew you to this topic, and what do you think it reveals about national memory and gender narratives?

My interest in female heroism began early, shaped by personal experience. Growing up, I noticed how schoolbooks often portrayed a narrow image of family life: Fathers go to office while mothers stay at home. That was far from my own reality: my mother was working (she was a school headmaster), while my father often worked from home, cooked, and cared for us. That dissonance made me question how gender roles are represented and why certain stories are elevated while others are not. On a larger scale, my PhD became an attempt to understand the same tension: what makes someone visible as a “hero,” and whose depiction remains unseen. I dedicated my thesis to my parents, especially my late father, Abubakar, who passed away during my fellowship at ARI in March 2025. Now that I am called Dr Abubakar, I feel that title belongs to him as much as to me.

Cut Nyak Din’s story has been part of my life since childhood in Aceh and Indonesia in general. Her name is ubiquitously on schoolbooks, street signs, banknotes, and in film. Yet when I looked closer, I saw that most accounts relied on a handful of images and state-sanctioned narratives. That curiosity became the heart of my PhD. I traced her representations across Dutch colonial records, Acehnese oral traditions, Indonesian literature and film, and more recent commemorations, in order to understand the complexities behind the icon.

What emerged was a picture of heroism that is constantly shifting. In Dutch accounts she appeared as an honoured enemy, in Acehnese memory a devout symbol of resistance, and in Indonesian state discourse a disciplined nationalist icon. Each version revealed less about Cut Nyak Din herself than about the anxieties and ambitions of the moment remembering her. Her story highlights both the possibilities and the limits of women’s inclusion in Indonesia’s national canon. On the surface, celebrating female heroes looks like progress. Yet their memory is often framed through male defined standards, military sacrifice, loyalty, or maternal devotion, reinforcing the very gender hierarchies.

One of the most striking examples of this tension is visual. In Leiden I found the only surviving photograph of Cut Nyak Din, taken after her capture by Lieutenant E. van Vuren. She sits at the centre of the image, visibly dignified even in defeat, yet the photograph identifies her in relation to her husband, Teuku Umar, rather than on her own terms. Every other likeness we see of her today is a reconstruction, later artistic remakes that reproduce, rather than originate from, her image. This single photograph therefore carries immense symbolic weight. It is both a trace of her historical presence and a reminder of how women’s visibility in archives is shaped by male figures and colonial authority.

Figure 5: Tjoet Nja Din, de vrouw van Teukoe Oemar, (zittend in het midden) gevangengenomen door luitenant E. van Vuren [Tjoet Nja Din, the wife of Teukoe Oemar, (sitting in the middle) captured by Lieutenant E. van Vuren].

Figure 5: Tjoet Nja Din, de vrouw van Teukoe Oemar, (zittend in het midden) gevangengenomen door luitenant E. van Vuren [Tjoet Nja Din, the wife of Teukoe Oemar, (sitting in the middle) captured by Lieutenant E. van Vuren].

Like in many places, history in Indonesia is never confined to textbooks or monuments. Those provide the official script, but popular culture keeps rewriting the lines. The 1988 film Tjoet Nja’ Dhien, remastered in 2021, gave Cut Nyak Din an emotional depth that no schoolbook could. Today, social media accelerates this process: heroes appear in memes and viral posts, photoshopped into humorous scenes, and mobilised in activist campaigns. These playful practices may look lighthearted, but they reveal how young Indonesians negotiate history, making it relevant to their own concerns and political realities.

Popular culture, then, plays a dual role. It democratises memory by making it more accessible and participatory, while also exposing the fragility of official narratives. Cut Nyak Din, like many heroes, continues to evolve, claimed, challenged, and reimagined by each generation.

What's one piece of advice you'd give to young scholars?

It would probably be to trust your own timeline and embrace the detours and pauses. Academia often feels like a race towards publishing, funding, or the next position but meaningful work requires patience. Slowness is underrated. Many of my clearest insights came not when I was rushing to meet a deadline, but in quieter moments: listening to community conversations in Aceh, stumbling across forgotten traces in archives, or attending events outside my immediate field. The uncertainties and setbacks of academia can feel daunting, but they often open new directions you could not have planned for.

One challenge that is rarely spoken about is the transition between completing a PhD and finding stability afterwards. For me, staying open to unexpected opportunities made all the difference. Applying widely and saying yes led me from fellowships at Cambridge, Leiden, and the Leibniz Institute, to upcoming ones in Turkey and Qatar, and now to my current role as NUS Fellow at ARI. Each fellowship not only gave me precious time and space to write, but also expanded my networks and perspectives, shaping my work in ways I could not have anticipated.

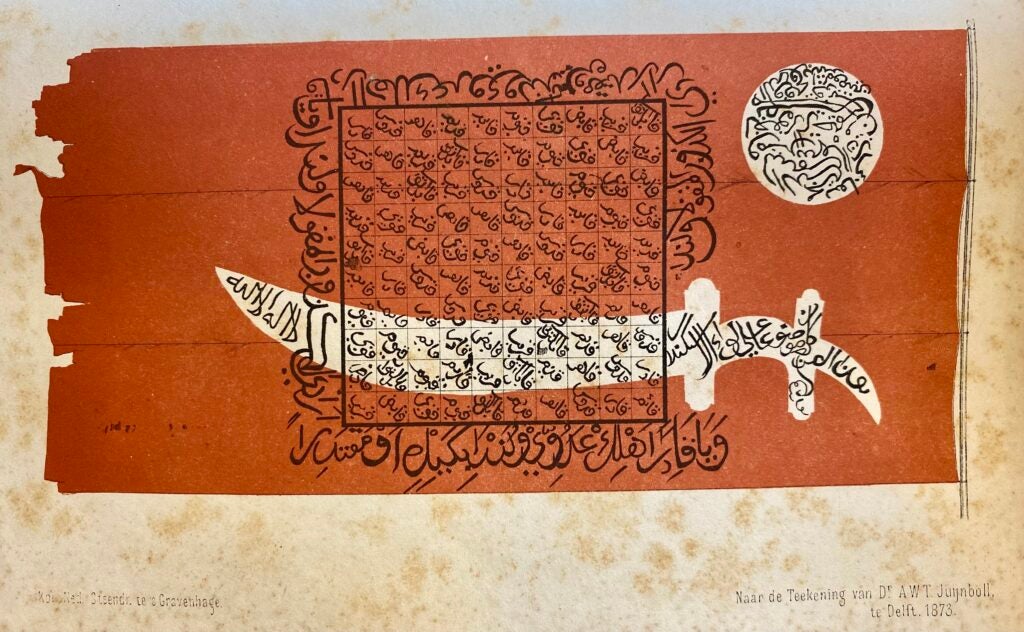

Figure 6: Aceh Flag ca 1840

Figure 6: Aceh Flag ca 1840

I would also say: your background can be your greatest resource. Growing up, I often felt self conscious about my strong Acehnese accent and never listed Acehnese as one of my official language skills. Yet that fluency gave me access to hikayat and oral traditions that opened indigenous perspectives few others could reach. My years in a dayah (Islamic boarding school) also equipped me with literacy in Jawi and Arabic, which allowed me to work directly with manuscripts and sources that might otherwise have remained closed to me. What once felt like a limitation: an accent, a modest background, or a non-linear academic path, has instead become the very foundation of my scholarship. Those lived experiences, rooted in place, language, and community, are resources no training or theory can replicate.

Finally, remember that scholarship is a collective endeavour. Seek mentors and peers who support you and be that person for others too. At the end of the day, our legacy as scholars lies not only in how many publications we produce, but in the communities we help to nurture and grow along the way.

The views expressed in this forum are those of the individual authors and do not represent the views of the Asia Research Institute, National University of Singapore, or the institutions to which the authors are attached.

Dr Myra Mentari Abubakar commenced her NUS Fellowship with the Asian Urbanisms Cluster with effect from 9 December 2024.

She completed her PhD in 2024 at The Australian National University and is currently engaged in extensive research on the hero phenomenon across Indonesia and Southeast Asia. Affiliated with the International Centre for Aceh and Indian Ocean Studies (ICAIOS) in Aceh, her research primarily focuses on gender and cultural history with an emphasis on Indonesia. At ARI, Dr Myra will explore the complex dynamics of memory and heritage in urban settings. She seeks to shed fresh light on cultural and historical framework by tracing how sites of hero legacy and gendered narratives shape public spaces and collective memory within urban landscapes.