Muscular India: Middle-class men, masculinity and muscles in urban space

Introduction

It took three movies and a magazine to popularise a new bodily ideal among middle-class men in India in the past decade or so. Characterised by bulging biceps, rock-hard abs and visibly pronounced pecs, this ideal diverges markedly from the healthy- potbelly of yesteryear’s middle-class male. For an older generation of fitness trainers and bodybuilders, the Salman Khan hit-movie Pyaar Kiya to Darna Kya (1998) was the first time they were reminded of what could be achieved with their bodies.

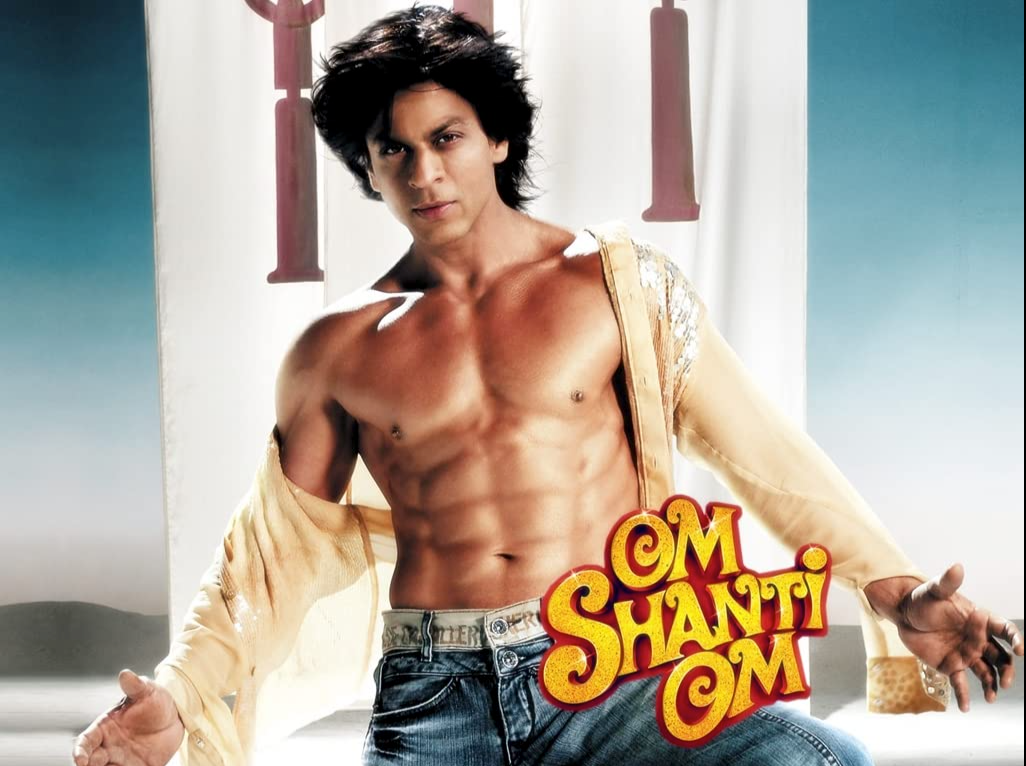

However, the real and very rapid growth in terms of gym memberships and demand for personal training only commenced when Shah Rukh Khan revealed his six-pack abs in Om Shanthi Om (2007). Since Aamir Khan’s Ghajini (2008) almost no Bollywood movie can do without a story of the lead actor’s transformation. India’s edition of Men’s Health which was launched in 2007 did something similar by focusing on the scope for middle-class men to transform their bodies along such ideals.

Making use of cover models who were not celebrities, it confirmed the potential of the Indian male body beyond Bollywood’s elite. What is this body precisely about? Why has it so rapidly taken root among middle-class men? And where do all these men who have found employment as fitness or personal trainers come from?

Muscular India builds upon an almost decade-long research engagement with lower middle-class men who work as fitness trainers and compete in bodybuilding competitions. In general these men hail from lower (new) middle-class families who have received most of their education in a vernacular language.

Attracting an ever-growing number of middle-class Indians struggling with issues of weight-gain and desiring to emulate the new muscular bodily ideal, these trainers are held to have the key to physical transformation. However, as much as they are admired for their bodies, the economic and social distance between them and their clients remain significant. However, this also presents an opportunity for social mobility.

Interacting with upper middle-class clients helps trainers improve their English and acquire knowledge of the kind of lifestyles they ambition for themselves. Their muscular bodies buy them a way into something that would have otherwise kept its doors resolutely shut.

Yet, relationships between trainers and clients continue to be revealing for the boundaries and hierarchies that separate different layers of the Indian middle-class. As much as change and limitless opportunities characterise the narrative of a new and rapidly changing India, this is where we start to understand why upward socioeconomic mobility can be such a sluggish process as well.

The new Indian male in the gym

Muscular India opens with a chapter that discusses the way the city of Mumbai, India’s economic heart and home to its most famous movie industry, plays a role in the lives of two fitness trainers, Kishore and Vijay. Each chapter in the book introduces in this way a new set of protagonists whose life course trajectories bring to the fore different but interlinked issues. During the final day of Ganesh Chaturthi we follow Kishore and Vijay as they make their way shirtless across the city to deliver their neighbourhood’s fourteen-foot tall Ganesha from Chembur to the Dadar seaside.

Meanwhile, the festival itself disrupts the city’s usual flow of movement. Even if it may appear that the city stands united in delivering their towering idols to the seashore, the route travelled is characterised by the kind of socioeconomic difference that these men also experience when they meet their clients in neighbourhoods much wealthier than their own native Chembur. One of the principle aims of this first chapter is to show that India is never not diverse or divided and this also goes for those considering themselves belonging to the middle-class.

The next chapter continues this discussion by focusing on the manager, two of his trainers and the clients of a small neighbourhood gym called BodyHolics in South Delhi. Manish hails from the urban village of Chirag Dilli, located only a few kilometres from the decidedly upper middle-class neighbourhood of GKII where he manages the gym and employs an ever changing number of trainers, including Amit.

Hailing from similarly new lower middle-class families, Manish and Amit are joined by Ravi who grew up in an upper middle-class environment. Much to the dismay of his family Ravi has also decided to join the fitness industry. Following all three over a substantial period of time, we observe how each in their own way seeks to navigate and negotiate class boundaries. The context which fuels their aspirations is urban India itself, with its ubiquitous building sides, new shopping malls, and desirable middle-class lifestyles advertised on enormous billboards. These ambitions are not without risk and fiasco.

Building bodies and generating capital

Muscular India then turns to the question of what it actually takes to build a muscular body and to develop what could be understood as bodily capital. The case of Victor, a Chennai-based bodybuilder, provides insight here. An IT manager with a multinational company, Victor’s true passion lies in competing as a bodybuilder. Eventually he will give up his career in IT and start his own personal training business, something which means a significant financial risk.

Victor’s case is contrasted with that of Akash, a Bangalore-based bodybuilder with international ambitions and who is a personal trainer with Gold’s Gym in an upper middle-class neighbourhood in the city. Both have heavily invested in their bodies in order to compete in bodybuilding tournaments but the prize money itself is not nearly enough to compensate for the investments made. Besides that, the sheer muscularity and size of their bodies mean that they are gradually moving away from the lean, muscular ideal that their clients desire.

Meanwhile, the organisation of the sport and its myriad organisations involved not only pose significant constraints on their ambitions as aspiring bodybuilders, but also show the kind of instable and murky world they operate in. The risk-taking involved and inherent precarity that come with building a career in fitness and striving to be competitive in bodybuilding tend to complicate trajectories for men such as Viktor and Akash.

Meeting Kishore from the first chapter again, the book continues to discuss risk-taking behaviour and the precarious existence that might be a long-term consequence of attempting to ascend the middle-class ladder. Kishore’s father, who spent most of his life working in the textile mills, dealt with financial precarity throughout his life. Kishore is now able to provide his family with a middle-class lifestyle that could not be more different than his own upbringing in a house which he describes as a little more than a hut.

Working from a young age in typically working class odd jobs, he now shops in air-conditioned malls, is able to afford branded clothing and owns his own car and custom-fitted motorcycle. Yet this middle-class lifestyle does come at a cost. The question this raises is how trainers relate to the risk of financial precarity as part of their upward mobility.

This is contrasted with the way upper middle-class clients of a CrossFit Box in Delhi negotiate questions of their bodies and the associated notions of masculinity. Taking into account that their muscular bodies matter very little to their jobs as highly educated professionals, this brings us to an important question of what this body precisely is about beyond its immediate use for fitness trainers and bodybuilders.

The reader then gets also introduced to Chennai-based bodybuilder Raj, who struggles with the question of whether he should invest in growth hormones to take his body to the next level. Since he has a well paid job as an IT professional, why then this body? Case material from another up-and-coming bodybuilder and his involvement in MuscleMania, an allegedly clean and natural bodybuilding competition, shows that questions of knowledge and what can be known remain crucial factors in the way trajectories take shape and direction.

Rapid urban change and new consumerism

With reference to India’s rapidly changing urban landscape, the book returns to Delhi to investigate the fast-growing sport of bodybuilding. We follow Delhi-based bodybuilder and personal trainer Shivam as he participates in his first competition. Organised by a Gujjar-dominated bodybuilding federation, most of its members hail from families for whom being middle-class is a very recent development even though many are now financially well off due to the sale of ancestral property located on the outskirts of the National Capital Region.

By following Shivam in his endeavours to make a name for himself in the fitness industry, we are able to reflect on the way new middle-class wealth is perceived by an older South Delhi-based upper middle-class. It returns to the question of masculinity, especially in the way it evokes negative associations with reference to newcomers to middle-class ranks who hail from NCR’s peripheral areas. What makes Delhi’s new middle-class ‘villagers’ being held accountable for the city’s many ailments, even jeopardising its future potential as a world-class city?

While bodybuilders and their coaches who are involved in the Gujjar-dominated federation are deeply committed to meeting globalised standards of bodybuilding, the desire to build muscular bodies also means successfully negotiating the perceived gap that separates rural from urban, lower from upper.

In the final chapter, Muscular India turns to the question of how an older and newer middle-class reflect on each other. How do trainers and bodybuilders relate to their muscular selves considering that their bodies are not only admired but also sexually desired? Taking a YouTube production by an NCR-based filmmaker as a point of departure, it addresses the potential for abuse and exploitation within a context that is characterised by a sizeable gap between lower and upper middle-class men in terms of economic and social capital.

Selvam, a Chennai-based personal trainer, through his involvement in photoshoots to build a modelling portfolio, has now turned to providing escort work to well-off male clients. Although he identifies as straight himself, he sees sex and porn work as a natural extension of his fitness career and is even expected to do so.

Conclusion

While for an older generation of fitness trainers and bodybuilders, Salman Khan’s hit-movie Pyaar Kiya to Darna Kya (1998) was the first time they were reminded of what could be achieved with their bodies, the more recent rapid growth in terms of gym memberships only commenced when actor Shah Rukh Khan revealed his six-pack abs in Om Shanthi Om (2007).

Since Aamir Khan’s Ghajini (2008) almost no Bollywood movie can do without a story of the lead actor’s bodily transformation. As a result the occupational category of providing fitness/personal training emerged, offering new opportunities for socioeconomic upward mobility for the men portrayed in Muscular India. Their bodily capital can potentially compensate for a lack of socioeconomic capital.

When the Indian edition of Men’s Health was launched in 2007 it featured an ‘unknown’ cover model, signalling that any Indian men could stand out from the crowd. By engaging with what this lean muscularity precisely stands for, the appeal it has across class boundaries, and the way it is put to use, Muscular India offers a unique and very different insight into the dynamics of a New India.

The views expressed in this forum are those of the individual authors and do not represent the views of the Asia Research Institute, National University of Singapore, or the institutions to which the authors are attached.