Nature-based Carbon Credits in Southeast Asia: Where Intergenerational Justice Meets Second-order Climate Justice

In December last year, the 28th edition of the Conference of Parties of the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC COP28) was concluded in Dubai, United Arab Emirates. For the first time in 30 years of climate change negotiations, a pledge was successfully made to transition away from fossil fuels by 2050, showing international recognition that decarbonising our fossil fuel-dependent economy is paramount to address climate change. However, a disappointment was the stalemate for Article 6, which organises a set of rules to structure the global market for the trading of carbon credits. This is important because despite current efforts of nations and businesses to reduce their carbon footprint, there is still a small proportion of emissions that is very difficult to eliminate. These emissions have to be offset through the trading of carbon credits, in order for an entity (a company or a country) to meet its net-zero targets. Businesses have shown that they are increasingly keen to offset their carbon emissions, with over half of the carbon credits purchased being nature-based (e.g., through reducing deforestation). This momentum has been increasing since COP26 (2021). However, recent media reporting has shaken confidence in carbon offsetting, leading to a lack of progress for Article 6 at COP28.

In this article, we introduce the idea of carbon credits trading, its relevance to Southeast Asia, and highlight some of the on-the-ground concerns about carbon projects. Singapore facilitates the transactions of high quantities of carbon credits, while its neighbours in Southeast Asia are sites for implementing nature-based carbon projects. Our aim is to use the lens of climate justice to facilitate an understanding of the potential impacts of activities and decisions made in Singapore on the diverse social-ecological contexts of Southeast Asia.

Climate justice is the idea that climate change has different social, economic, public health and other adverse effects on underprivileged populations who have the least responsibility for causing it. In international fora like the UNFCCC, it is typically discussed in terms of how (1) the costs and benefits of climate change are unfairly allocated spatially (distributive justice) and (2) those most affected by climate change are often excluded from the decision-making process regarding responses to the problem (procedural justice). In inquiring into nature-based carbon trading in Southeast Asia, two dimensions of climate justice stand out. The first is intergenerational climate justice, which recognises that climate change has profound and lasting impacts on the lives of future generations. It can also be argued that as this generation is already witnessing shifting weather patterns and a higher frequency of extreme weather events, the effects of climate change have become “intra-generational”. The second is what we term second-order climate justice, or the social and environmental concerns arising not from the effects of climate change, but from efforts to address climate change. Nature-based carbon credits are where intergenerational justice and second-order climate justice meet, and hence they should not only address climate concerns but should also adequately minimise the social and environmental impacts associated with their implementation.

What are carbon credits, what is a carbon market, and how do they work?

A carbon credit is a tradeable unit representing the reduction or removal of one tonne of carbon dioxide equivalent. Carbon credits can be generated through reduction or removal activities. Removal carbon credits include nature-based credits developed under reforestation or technology-based projects such as Direct Air Capture (DAC). Examples of reduction carbon credits include projects that replace wood-based fuel with solar energy or developing cookstoves that improve the efficiency of wood-based cooking. Carbon offsetting occurs when individuals or companies retire carbon credits against their own carbon emissions footprint. The idea of carbon offsetting through mechanisms like the Clean Development Mechanism and the Reducing Emissions from Deforestation and Forest Degradation Plus (REDD+) has been in existence for almost two decades.

A carbon market is where carbon credits are traded. Currently, there are two types of markets for carbon credits. The first is the compliance carbon market, which is a product of policy or regulatory requirements by a jurisdiction (at the sub-national, national, regional, or international scale). For example, emissions trading systems have been set up in New Zealand, China, the United States and the European Union for regulated businesses to comply with the cap-and-trade policy of their respective jurisdictions. The second is the voluntary carbon market (VCM), which allows non-regulated entities to address their climate impact. The trading of carbon credits is facilitated through carbon exchanges, which function like stock exchanges.

For example at VCM carbon exchanges, such as ACX (formerly AirCarbon Exchange), there are three ways in which carbon is traded. The first is the spot exchange, which allows for efficient trading of carbon credits and near instantaneous settlement. These carbon credits have been categorised into standardised contracts (baskets of similar carbon credits that meet specific criteria, e.g., ACX CORSIA Eligible Tonnes are carbon credits that are eligible under the Carbon Offsetting and Reduction Scheme for International Aviation (CORSIA) scheme, the global offsetting scheme for airlines and airline aircraft operators), thereby simplifying the process for large corporate buyers to purchase carbon credits in their desired volumes without extensive verification. The second way to trade carbon is through the Carbon Markets Board, where buyers choose from a list of carbon credit projects. Finally, auctions allow project developers to sell their credits at a set minimum price while facilitating price discovery for new types of carbon projects. The idea is that this market-based mechanism helps limit carbon emissions into the atmosphere, thereby facilitating intergenerational climate justice.

Why should Southeast Asia care about carbon trading?

Southeast Asia has witnessed rapid deforestation in the past 30 years and deforestation rates remain high despite a slight reduction in recent years. Besides government enforcement against deforestation, funds are needed to create economic and livelihood alternatives to logging and forest clearing. Globally, it is estimated that $460 billion per year is needed to end deforestation, but less than one per cent of this funding is available. There is also little incentive for governments to prevent deforestation, especially in areas with low biodiversity or ecotourism importance. Despite foreknowledge of the issues, traditional funding sources of charities, governments, and NGOs have never been enough to fund poverty-related economic development which would spare the need to cut forests to generate capital. Carbon trading and the REDD+ can help to address this shortfall in funding.

In this map of Southeast Asia, the red areas indicate the areas where forests have been converted to other land cover types between 2000 and 2019. The green areas indicate the intact forests. Source: EarthEnginePartners.

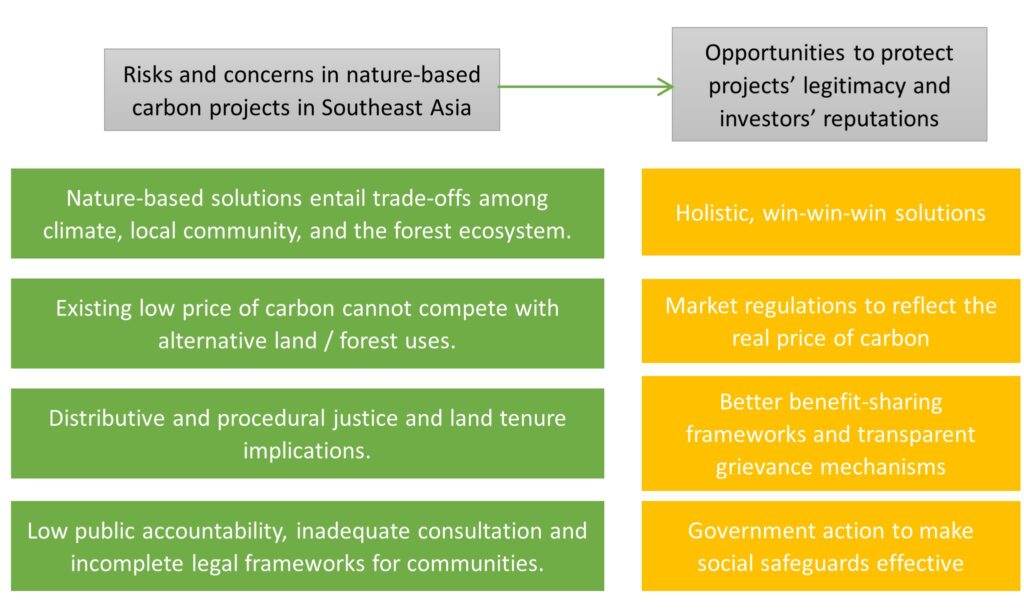

However, the protocols behind implementing a nature-based carbon project to generate carbon credits are still relatively new and evolving. This means that there is a lot of experimentation and learning of best practices and their potential long-term social and environmental consequences. This is particularly so because the number of credits generated depends on a detailed look at past activities and drivers. Projecting this into the future is also extremely complicated. Besides meeting significant technical demands to design and monitor carbon projects, the highly heterogeneous political and social-ecological setting of Southeast Asia poses another challenge: it is necessary to be attuned to local contexts rather than apply template project designs. These lead to concerns about second-order climate justice in the implementation of nature-based carbon projects.

Concerns about second-order climate justice in nature-based carbon projects in Southeast Asia

First, land and forest use decisions for economic development usually involve trade-offs. For example, the planting of large-scale monocultures of non-native tree species–such as rubber plantations in Cambodia, with rubber being native to South America–theoretically sequesters carbon from the atmosphere. However, if it is done without due consideration of the existing ecology and customary land use, it comes at the expense of biodiversity and social protection. In designing carbon projects involving nature-based carbon sinks, attention needs to be paid to the potential trade-offs. Holistic solutions (e.g., agroforestry, traditional ecological knowledge) is needed to deliver positive impacts for the climate, the local community, and nature.

Second, the low price of carbon cannot compete with alternative land and forest uses. The economic returns of cash crops are too attractive and have driven the conversion of large tracts of land for cassava and maize production in mainland Southeast Asia in recent years. Revenues from carbon credits can only be deemed as top-ups to an existing revenue source (e.g., for tree plantation companies already invested in sustainable forestry operations) rather than as an incentive for inducing systemic changes in land use. For nature-based carbon projects to adequately address the shortfall in forest conservation funding, there should first be market regulations to reflect the real price of carbon.

Third, while additional carbon revenues to forest or agricultural systems create new incentives for reforestation and offer protections against deforestation, fundamental questions remain regarding the distributive and procedural equity of carbon projects. For example, in Cambodia, Laos, and Vietnam, forested areas are managed by the state, but there are also people living in those areas. How should revenues from a carbon project be shared between governments, project developers, and local communities? Moreover, what are the implications for land tenure? While some nature-based carbon projects have received positive feedback, others have been criticised for causing negative impacts such as displacing vulnerable populations.

Fourth, the state-centric nature of the UNFCCC, such as the jurisdictional and nested approaches to REDD+, assumes that the state will meaningfully represent the interests of its people and has the capacity to regulate and monitor the implementation of nature-based carbon projects. However, this may not be true when public accountability is low and laws are enacted without significant public consultation. Although social safeguards are required in REDD+ projects, how they have been applied in practice has raised practical concerns about implied coercion. Free, Prior and Informed Consent (FPIC) processes could be superficially implemented without true consideration by the communities, and official grievance mechanisms may be seldom used. Existing legal frameworks, such as those within state forest or protected areas that do not recognise customary tenure, could limit communities’ land use options and present doubts about the genuine freedom and consent of communities. All these inherent limitations are practical hurdles to procedural justice.

The relatively young nature of nature-based carbon projects means that there is an opportunity to address these risks, such as through test-driving better approaches to benefit-sharing locally, a more adequate engagement of communities, and implementing more transparent grievance mechanisms to meet the increasingly high requirements of voluntary carbon standards. Given the imminent nesting of voluntary projects within jurisdictions, carbon project developers will have to work ever more closely with governments and communities. In so doing, they can share best-practices and seek clearer governmental legislation and enforcement action for effective social safeguards. For example, the formalisation of land and forest tenure for forest-dependent communities and clear guidelines for benefit-sharing will help to facilitate the smooth implementation of carbon projects. This guarantees the social and political legitimacy of carbon projects and protects the reputations of investors as well.

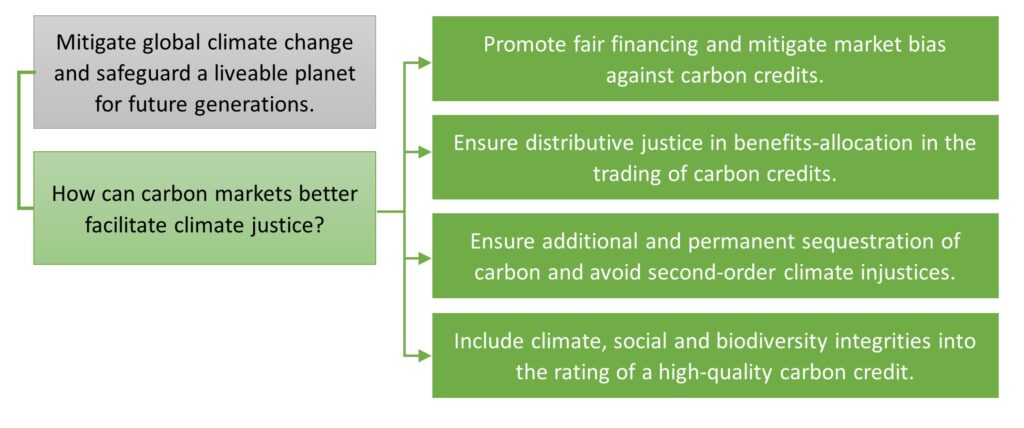

How can carbon markets better facilitate climate justice?

Intending to facilitate investments in projects that mitigate global climate change and safeguard a liveable planet for future generations, carbon markets are in line with intergenerational climate justice. Yet, in carbon markets, a peculiar behaviour observed since early-2022 is a preference for younger vintages (age) of nature-based carbon credits. Older vintages are viewed as lower quality by investors and are discounted on the carbon market. However, there is no logical basis for this view since the estimated amount of carbon sequestered is immutable with time. It is even arguable that an older vintage has done greater service by storing carbon in an ecosystem for a longer time. This recent behaviour in carbon markets is a barrier to the equitable financing of carbon projects.

Besides intergenerational climate justice, there are concerns about distributive justice within the system. A frequent criticism of carbon markets is when speculative trading raises the price of carbon credits, it is only the speculative investor who profits. To address this, carbon exchanges such as ACX use their proprietary technology to track and trace the carbon credits trading within the exchange. This makes it possible for a stream of royalties to be allocated back to project developers as carbon credits traded on the exchange, ensuring a more equitable flow of cash back to local indigenous communities, in accordance with the project’s benefit-sharing framework.

Moreover, there are further risks of second-order climate injustices arising from investors’ demands for high climate-integrity carbon credits. Climate integrity is judged in terms of whether a carbon project has demonstrated the additional and permanent sequestration of carbon. However, there have been doubts about the validity of nature-based carbon credits, such as those reported by The Guardian in early 2023. While most of the assumptions behind the article have since been debunked by scientists and practitioners in the field (See Coleman et al., 2023; Moroge, 2023; Morris et al., 2023; Verra Response to Guardian Article on Carbon Offsets, 2023; Mitchard et al, 2023), substantial public engagement is still needed to correct this misperception. In response, the protocols for estimating carbon emissions reductions are being tightened, making carbon project development more challenging.

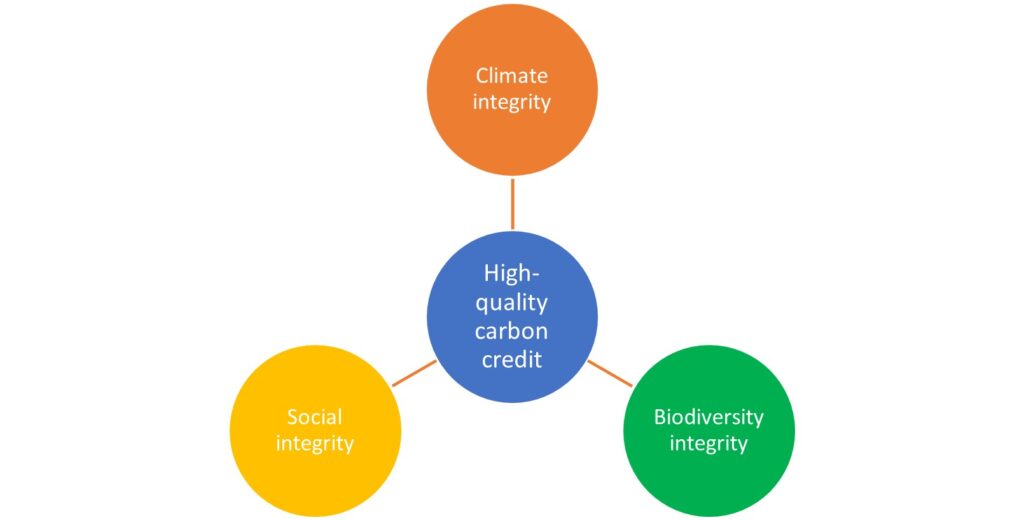

As it is, the measurement, reporting, and verification activities in a carbon project need to be funded and this tends to alienate local communities who do not have sufficient capital to initiate their own carbon credit project. The increasing demands for high-climate integrity carbon credits will lead to higher project implementation costs, such as the use of more advanced remote sensing technology to monitor forest carbon stocks at higher spatial-temporal resolutions. There is significant irony in this trend: the early discussions around REDD+ were that it can play a role in restorative climate justice–that those responsible for climate change should help to make up for its harmful effects–and were premised on its potential to alleviate poverty and improve livelihoods. This trend, however, will likely suppress the amount of benefits distributed to local communities and reduces the resources available for important on-the-ground monitoring of social outcomes. While some carbon credits have certified biodiversity co-benefits, the current behaviour in carbon markets inclines towards the climate integrity of the credits. To address this, the agencies that rate carbon credits should broaden the definition of a high-quality carbon credit to include the social integrity and the biodiversity integrity of these projects.

Conclusion

At COP28, progress on setting rules for global carbon markets stalled because the European Union, Latin American, and African states wanted tighter rules and higher scrutiny levels for carbon projects. This is likely a consequence of doubts raised in recent years over the climate integrity of such projects. While some say this impasse slows climate action that leads to intergenerational justice, others argue that this was better than a poorly-forged deal. We hope that the continued work of formulating tighter rules will also prioritise the social and biodiversity integrity of carbon credits. As we have tried to show through Southeast Asia, nature-based carbon projects are where intergenerational climate justice and second-order climate justice meet. It is crucial to understand their impact, not only on carbon sequestration but also on local communities who live with and depend on nature-based carbon sinks. More dialogue is needed between corporate sector investors, carbon project developers, and civil society, who may have different views about how carbon markets work but share a common objective and interest in climate and social-ecological justice. This will benefit the young, evolving, and contextually heterogeneous field of carbon project development and carbon credits trading, with the hopes of achieving justice for all.

Acknowledgements

We thank the three panellists for contributing their valuable insights during the ARI Roundtable on 9 October 2023:

- Ms Hum Wei Mei, Head of APAC & Global Head Carbon and Environmental Products at ACX

- Dr Lahiru Wijedasa, Asia Forest Coordinator of Birdlife International

- Dr Micah Ingalls, Team Leader of the Mekong Region Land Governance project

We also thank Dr Michelle Miller (Senior Research Fellow, Asia Research Institute, NUS), Ms Shakura Bashir (PhD student, NUS), Ms Melissa Low (PhD student, NUS) and Dr Rob Cole (Responsible Agriculture Investment Adviser, MRLG) for their inputs to the ideation of this Roundtable.

This article benefited from financial support provided by the Ministry of Education, Singapore, under its Social Science Research Council (SSRC) grant “Climate Governance of Nature-based Carbon Sinks in Southeast Asia” (MOE2021-SSRTG-021). Any opinions, findings and conclusions or recommendations expressed in this material are those of the authors and do not reflect the views of the funding body.

The views expressed in this forum are those of the individual authors and do not represent the views of the Asia Research Institute, National University of Singapore, or the institutions to which the authors are attached.

Wei Mei Hum is concurrently, Head of Asia Pacific and Global Head of Carbon & Environmental Products in ACX. She also acts as an In-House consultant and helps to ensure that ACX’s processes, market rules & guidance, are aligned to international best practices. She represents ACX on several industry led task forces and committees.

Lahiru Wijedasa is Asia Forest Coordinator for BirdLife, where he works with partners to design and implement long-term end-to-end forest projects such as REDD+ carbon projects. He is also part of the SCeNE coaliton, which gathers leading conservation organizations to provide guidance in what good carbon projects mean for biodiversity and communities (i.e. triple benefits).

Micah Ingalls serves as Team Leader of the Mekong Region Land Governance (MRLG) Project which promotes the tenure security of smallholder farmers in Cambodia, Laos, Myanmar and Vietnam. He has more than 20 years of experience in South, Central and Southeast Asia, working with the United Nations, development agencies and academia.