Can the One Piece Flag in Nepal’s Gen Z Protest Be an Inter-Asia Referencing Practice?

On 8 September 2025, Nepal’s Generation Z flooded the streets in a protest that would reshape the nation’s political landscape. Triggered by the government’s abrupt ban on major social media platforms, widely seen as a desperate attempt to suppress criticism, the protests quickly transcended the question of digital rights to express broader frustrations. Years of corruption, underemployment, and stalled infrastructure had left a generation disillusioned with the promises of democracy and development. The initially peaceful and even lively protests, however, escalated into violent and tragic confrontations where the state forces killed many innocent young people, and more were injured. Within two days, the movement had transformed state politics: Prime Minister K. P. Sharma Oli resigned, and Sushila Karki, the former Chief Justice, became Nepal’s first female Prime Minister, leading an interim government (For more details of the structural causes and consequences of the movement, please see Mulmi, 2025; Rana, 2025; SAV, 2025).

Among the banners and placards that filled Kathmandu’s streets, one symbol stood out, the Jolly Roger flag from the Japanese manga One Piece, modified and reimagined as an emblem of rebellion. Depicting a skull wearing a straw hat, this flag is the insignia of the “Straw Hat Pirates,” the fictional crew led by Monkey D. Luffy in Eiichiro Oda’s long-running series One Piece (1997–present). For protesters in Nepal, and elsewhere in Asia and the world, this flag, known globally through animation, film, and gaming, became a shorthand for courage, resistance, and freedom.

Figure 1: Nepali protesters holding the One Piece flag alongside the national flag. Source: @ animespotlight

The Straw Hat Flag: Manga, Political Icon, and Inter-Asia Cultural Politics

First serialised in Weekly Shōnen Jump in 1997, One Piece tells the story of Luffy and his crew’s quest to find the legendary treasure “One Piece” and achieve ultimate freedom. The Straw Hat Pirates are illustrated as freedom fighters, opposing the corrupt and autocratic “World Government.” Their flag encapsulates this ethos: a symbol of loyalty, courage, and defiance against power.

Over nearly three decades, One Piece has become a world-spanning cultural complex, generating films, merchandise, video games, and even a Netflix adaptation (a new season is coming). Beyond entertainment, scholars have recognised One Piece as a moral and political universe where friendship, justice, and rebellion against authority coexist within a neoliberal ethos of self-realisation, both echoing and shaping real-world politics through identity and narrative (Kopper, 2018).

During the Nepali protests, the flag appeared in multimodal forms. Protesters painted it on cardboard signs, juxtaposed with anti-corruption slogans. Others remixed One Piece’s “wanted posters,” replacing pirate faces with those of political leaders, complete with mock bounty amounts. Post-protest media coverage further amplified its visibility, extending the flag’s political life in the digital sphere. These creative appropriations blurred the boundaries between fandom and activism, revealing how pop-cultural infrastructures can become channels of political mobilisation.

Figure 2: A local protester holding One Piece–style ‘wanted’ posters featuring images of Nepal’s political leaders. Source: @ animespotlight

One common way to conceptualise the One Piece flag’s role in the Nepali Gen Z protest is through its articulation with broader networked movements (Cheng and Lee, 2023). Across Asia and beyond, the same flag, and its many variants, has been used by activists in various protests (Vaswani, 2025; Mark and Anamwathana, 2025). International observers often interpret the appearance and creative adaptation of the flag in Nepal as a direct outcome of social media circulation, framing it as evidence of emerging transnational solidarities and a broader shift toward social justice and democratic ideals (e.g. Jalli, 2025; Baharudin, 2025; Ratcliffe, 2025). Similar sentiments also emerge in Nepali accounts, where youth protesters frequently cite the flag’s prominent presence in Indonesian demonstrations earlier in the year as a key source of inspiration. Many have become attuned not only to the collective energy and determination expressed in One Piece’s narrative of resistance, but also to how these affective messages have been practically articulated within both regional and global political movements (Ghimire, 2025a; Ghimire, 2025b).

This under-the-same-flag imagination constructs a vision of inter-Asia solidarity, fighting against shared regional problems such as authoritarian governance, corruption, inequality, and underdevelopment. The imagined common enemy is accompanied by a universalised set of values defining what a good society and life should look like. In this sense, the discourse linking Nepal’s protest to others under the same flag echoes how movements like the “Milk Tea Alliance” (Matijasevich, 2024) construct transnational political alliances through popular cultural idioms, inviting Asian Cultural Studies practitioners to “return to the analysis of the ‘popular’ as a cultural-political concept” (Chua, 2016).

The Limits of Inter-Asia Solidarity

As Hieyoon Kim (2024) cautions in her critique of South Korean art activism supporting the Burmese struggle for democracy, inter-Asia solidarity often reproduces hierarchies even as it claims to transcend them. While popular culture creates new circuits of empathy and shared imagination, these circuits remain embedded within unequal infrastructures of cultural production and consumption. Neoliberal capitalism, soft-power dominance, platform capitalism, and global media industries, all shape what symbols circulate, and which affective idioms become legible as “Asian,” “democracy,” and “justice.”

While shared repertoires of resistance may form affective chains of reference, the under-the-same-flag discourse risks reducing diverse political struggles to a universal template of youthful rebellion. The romanticisation of “Asian youth solidarity” can obscure local complexities that structure Nepali society and its uneven relations with other Asian and global actors. The empathy fostered through shared icons, in other words, can flatten difference rather than deepen understanding.

This ambivalence echoes Kim’s observation that South–South empathy may “bar divergent forms of South–South relations from flourishing.” The One Piece flag thus invites us to ask: what forms of solidarity does it enable, and what forms does it silence? When protest aesthetics become too easily transferable, resistance risks becoming a meme, a reproducible, decontextualised commodity circulating within global attention economies.

Regrounding Local Popular Subjectivities

The Straw Hat flag fluttering over Kathmandu’s protest squares thus forms a living archive of inter-Asia politics, an emblem that gathers the hopes and disillusions of a generation navigating global modernity and postcolonial precarity. Under this shared flag, Nepali youth momentarily found a language to express their yearning for justice and freedom. But the real challenge—and promise—of inter-Asia solidarity lies not in waving the same symbols, but in learning how to listen across their differences.

Nepal has long been entangled in global economies of popular culture, albeit from a vulnerable position. This vulnerability manifests on two levels. First, the country itself has long been a product of consumption in global popular culture—most famously as the mythical “Shangri-La.” Among Asian nations, Japan has perhaps been the most adept at materialising this internal Orientalist imagination of Nepal, with manga and other pop-cultural products constructing and reaffirming Nepal’s “being-gazed” position in modern global culture.

Second, despite remaining one of the least developed countries in the world, Nepal’s exposure to global commodities, media, and imaginaries has grown exponentially even as its domestic industrial base has eroded. As Feyzi Ismail (2025) notes, decades of privatisation, remittance dependence, and the hollowing-out of productive industries have produced a generation of educated but underemployed youth—“economically starved, politically disillusioned,” yet deeply networked through digital media. Their everyday lives are shaped by a paradox: intimate proximity to global flows of information and imagery, coupled with structural exclusion from the prosperity these images promise.

The global economy of popular culture has thus intensified an anxiety of modernity deeply embedded in Nepali everyday life. It encapsulates the contradictions of Nepali modernity: a generation hyper-connected yet materially precarious, globally literate yet nationally abandoned. This anxiety is not merely psychological but structural. As remittances sustain households while draining labour, and as higher education produces degrees without employment, modernity itself becomes a suspended horizon. Popular culture fills this vacuum by offering narratives of agency that politics no longer provides.

But who are the popular in the popular culture of Nepal? As Chua Beng Huat reminds us, returning to Stuart Hall’s understanding of popular culture as “the culture of the masses”, a culture not invented but already circulating within lived practices, its revolutionary potential lies in its everydayness. In Nepal, the “popular” are not only digital natives accessing global fandoms, but also rural families sustained by remittances, young women who have taken over agricultural labour, and migrant workers scattered across the Gulf, India, and Japan, where One Piece originated. Their stories, frustrations, and aspirations form the other layers of social ground from which the symbolic politics of the One Piece flag gains meaning.

As Ismail observes in the aftermath of the Gen Z protests, “What’s required is a very strong and ideologically committed political force, one that stays rooted in the people and is willing to govern on that basis.” Forging a Nepali and South Asian popular culture not linearly tied to neoliberal capitalism or liberal democracy, but attentive to the “third space” that takes cognisance of postcolonial entanglements to offer further Inter-Asia scholarship, will be a crucial part of that project.

Conclusion

The fulfilment of such a popular culture, whether in Nepal or across Asia, will not be an easy task. The aim of this short article is not to dismiss the connections forged through the One Piece flag as superficial or meaningless, nor to suggest that they are exclusive to urban youth with access to digital media and global popular culture. Rather, it seeks to draw attention to the issues that can be thought alongside these narratives of inter-Asia connectivity.

The One Piece flag in Nepal’s Gen Z protest, and in other Asian movements, materialises how postcolonial subjects negotiate the contradictions of being simultaneously connected and excluded, modern and peripheral. The anxiety of modernity, far from paralysing, can become a generative condition for reimagining solidarity, not as sameness under a shared icon, but as a polyphonic dialogue across uneven grounds.

The challenge, then, is to move from waving the same flag to cultivating the capacity to tell different stories under its shadow. This task is vital not only for Nepalis but for all Asians, to awaken from the too-good-to-be-true dream of connectivity. All this is far from easy, for every dimension of our lives has been irreversibly transformed. Yet perhaps keeping alive an awareness of these asymmetries, and nurturing the capacity to tell different stories, offers a beginning. Maybe this spirit, after all, more faithfully follows the original ethos of One Piece: justice not as universal sameness, but as a commitment to the shades and complexities of our worlds.

The views expressed in this forum are those of the individual authors and do not represent the views of the Asia Research Institute, National University of Singapore, or the institutions to which the authors are attached.

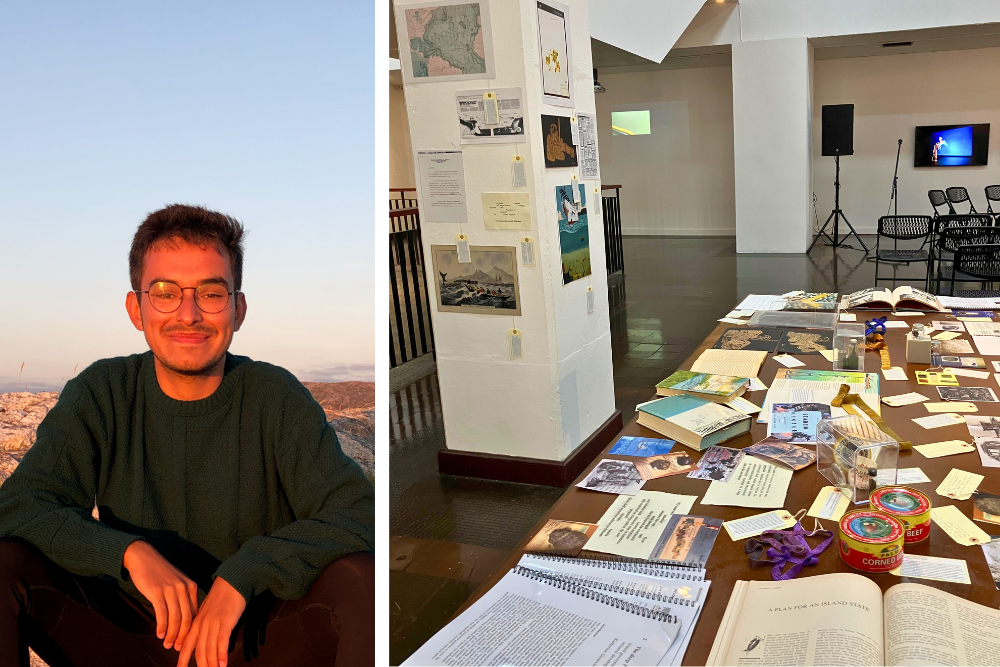

Dr Yang Zezhou commenced his appointment as a Postdoctoral Fellow with the Inter-Asia Engagements Cluster with effect from 21 January 2025.

Dr Yang graduated with a PhD in South Asian Studies from SOAS, University of London. At ARI, he will be engaged in his project that explores the trans-Himalayan circulation of Buddhist beads between Nepal and China. His scholarly interests include Trans-Himalayan studies, Global China and Nepal, inter-Asian, decolonising knowledge production, the Anthropocene and multimodality.

https://doi.org/10.25542/1163-8514