“Plants are like People”: Efficacy and Ecology in Lao Herbal Medicine

"Where does the power of the medicine come from? Is it in the plants, or in people?"

"Oh but plants…they’re like people! Actually, it’s the same thing."

Health, the environment, and medical efficacy are all issues at the forefront of public consciousness as we live through this anthropogenic era of pandemics and ecological crises. With new zoonotic diseases constantly emerging and the rapid decline of biodiversity closely associated with the loss of indigenous peoples, languages and knowledge, we increasingly need to take a multispecies perspective towards human and planetary wellbeing. So what insights can our relationships with plants – or theirs with us – provide in reflecting and acting on these important issues? In this article, I explore the use of plants as medicine in Laos and how – to repurpose the famous words of the anthropologist Claude Levi-Strauss – they are “good to think with” through their metaphorical and material entanglements with human worlds.

A forgotten nation?

Laos, a biodiversity hotspot with a highly rural and ethnically diverse population, is often referred to as a ‘forgotten’ country rarely appearing in world news or academic literature. Besides brief moments of notoriety, such as its recent economic crisis or the discovery of coronaviruses among bats that suggests Laos might have been a possible ground zero site for COVID-19, Laos rarely appears in either in world news or academic literature. This is not an accurate representation of the nation’s status as a land link between China and mainland southeast Asia, aptly symbolised by the new train line; or its rapid development through foreign investment such as hydropower for export, which is threatening local ecosystems and livelihoods along the water courses. From the perspective of traditional medicine, however, Laos remains an outlier among surrounding nations because its locally practised medical forms have undergone little transformation or standardisation. In the context of an under-resourced state biomedical system, healthcare integration - whilst promoted under socialism and a part of government policy - has remained primarily at an individual, informal level. Indeed, it is difficult to define ‘Lao medicine’, as there are almost no centralised or standardised sources of information such as textbooks, training schools or large treatment facilities in the country. Without significant state regulation, knowledge is still highly heterogenous. Although during COVID-19 the profile and funding for traditional medicine in Laos were briefly increased, and a number of herbal remedies were trialled to support the recovery of mild cases, production was limited by the lack of available raw plant material.

“Bitter is medicine”

During the time I spent living and conducting fieldwork in villages and healthcare settings in southern lowland Laos, it became a running joke to hear people utter the phrase “I don’t know anything about traditional medicine” when asked. However, when eating together, walking through the forest, gardening, or even taking public transport, encounters with plants would produce in-depth conversations and debates about home remedies, family knowledge, and journeys through the health system. Plants are an essential material element of social relations and for local health practices such as home sauna or meals. Like many Asian countries, there is no clear boundary between food and medicine, as shown in the popular saying “bitter is medicine” (kom pen ya). Many meals in Laos typically include fresh raw dark green vegetables or leaves with a bitter taste, especially during the hottest times of the year, which are said to have health-giving and cooling properties. During my research, I discovered that some of these culinary plants were also used in herbal remedies to treat malaria and had shown good efficacy in pharmacological studies. In fact, the use of bitter tasting plants to reduce febrile heat is common worldwide, and has been associated with the discovery of lifesaving anti-malaria drugs such as quinine and artemisinin. This type of informal knowledge about plant use which arises from everyday practices can therefore yield valuable insights for tackling current health crises.

In rural Laos, most people, especially of the older generation, still easily recognise and name plants. It is noticeable how the Lao names for plants often correspond to the emic category of illness they are known to treat. Furthermore, the morphology of the plant may mirror the affected body part and a specific disorder, showing how plants and humans are understood to be closely linked.

An example of this is a class of plants known as padong, with the name, shape, and colour of each matching the symptoms of particular disorders which affect the musculoskeletal system, also called padong. For example, a plant named padong kho (Atrabotrys sp.) is used to treat arthritis, also called padong kho. The word kho means hook, and the hook-shaped thorns mirror the hook shape of arthritic hands.

Likewise, a category of tree woods used in postpartum, nom (breast, swelling), is named after external protuberances on the bark which resemble nipples of different shapes of a woman, mouse, or cow – a discussion which caused much hilarity as I struggled to understand the meaning! A plant named sam phan hu (three thousand holes) has a rhizome which is punctuated by long narrow channels in the form of small holes on its surface, resembling the shape of fi (furuncles) in the body.

This principle of “like cures like” is well-known among ethnobotanists; in the western context this is termed the “law of similars” or the “doctrine of signatures” stemming back to Galen. Beyond herbal medicine, Lao healers also use the principle of “like produces like” for curative purposes, in which an object is considered to exert a matching effect–a phenomenon which has long been observed across cultures by anthropologists, often termed as “sympathetic magic”. Although the idea that this phenomenon is directly related to the efficacy of plants as medicine has been widely debunked, it gives a fascinating insight into how the flow of ecological-medicinal knowledge is culturally constructed and conceptualised – people ‘know’ through their engagements with plants without always realising it. Medicinal knowledge is thus represented through metaphor, and generated through bodily and social interactions with the environment.

This familiarity with plants is also important for the use of herbal medicines to treat illness. When visiting traditional healers, people often participate in the treatment process by finding the plant parts they are prescribed, and preparing their own medicines such as grinding the woody parts into cool water, a process which requires time and effort. This has a very real impact – active involvement in and understanding of one’s own medical treatment can improve health outcomes.

Potent plants

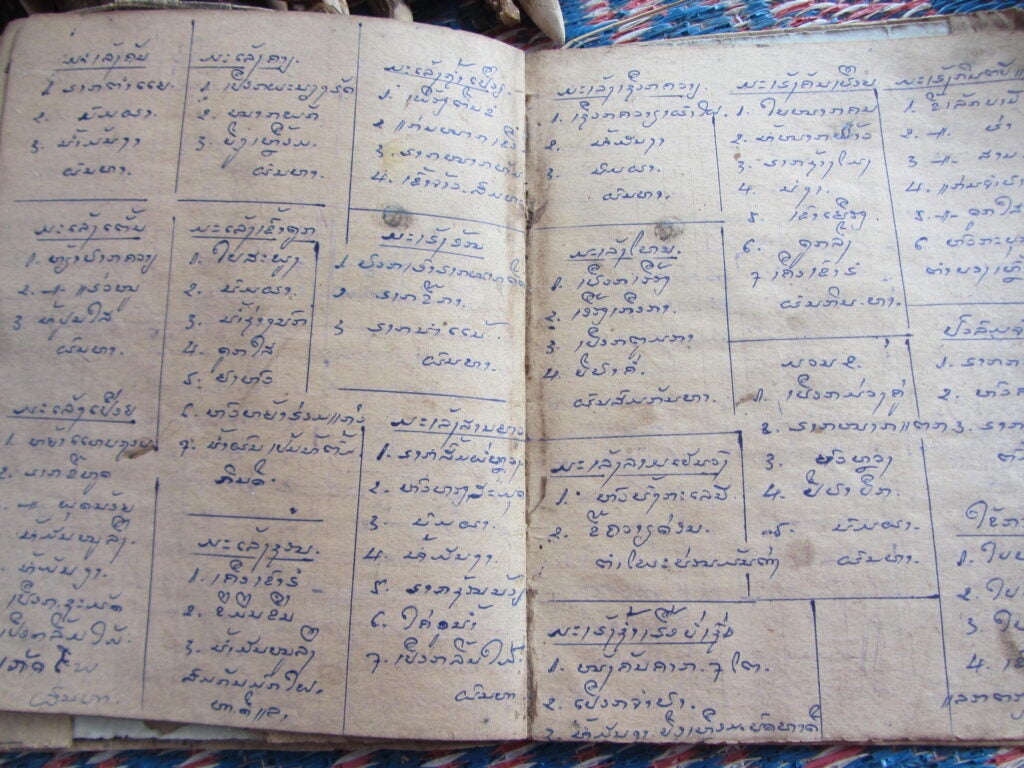

In addition to rural peoples’ intrinsic knowledge forms, my PhD research documented practices of traditional healers which incorporate unique lineages of transmitted knowledge. Although the specific method of each practitioner varies, it is based on the use of wild harvested plant materials such as roots, barks and leaves for the creation of personalised herbal medicines. These plant materials are said to possess potency due to their quality of being ‘fresh’ (sot). The process of finding the plants can be challenging, but the quest shapes social relations and is a means of establishing and exchanging shared knowledge.

A story which illustrates this is a journey we made with the village healer to replenish his medicine supply. We could not find one of the trees he needed, mak mo—it was not in the last place he saw it, so we asked villagers along the way, and inquired at houses of friends and relatives. Most people already knew this tree; for those who did not, the healer described its mottling on the trunk, the colour and shape of the leaves and so on. Some people asked me what it was for, and I explained how the wood was boiled to treat the liver; they were curious that a foreigner clearly considered this tree important enough to search for! Some said it could only be collected deep in the forest, difficult to access in the midst of the rainy season, and considered dangerous because of spirits. Eventually, we found a family who was taking a lunch break from rice planting, who said they had seen mak mo not far away, on the path through the forest on the way to their rice fields, and gave us a lift there on their small tractor. Beyond offering us a ride, they helped the healer to harvest some parts of branches and with a machete chopped them into large chunks of wood which he carefully placed inside a sack and carried back to the village on his old motorbike.

The discussion around the exact location of mak mo highlights the seasonal and changing relationships between humans and the environment. The family had seen mak mo because it was close to their rice fields, albeit not on their land, and they passed it daily during the planting season. The wood is harvested with the use of a machete and is not easy to bring back, especially during the rainy season when the dirt tracks are flooded. The loss of mak mo in the place where the healer last saw it may have been due to development of a new road, logging by villagers, or other unexplained reasons. In rural Laos, plants act in unpredictable ways—they die, are cut down, or go somewhere else of their own accord, and are often not where they are expected to be. Whilst human actions clearly impact the lives of plants, it can be argued that plants also possess agency and can exert influence on the social world of humans. Although plants in Laos are not attributed personhood or innate spiritual power, such as in Amazonian contexts, human engagement with medicinal plants is also mediated by the spirits who dwell in or govern the places where they are found.

The plant-human relationship is also crucial in understanding local conceptions of efficacy, which is intertwined with ethics and environmental concerns within the Lao healer’s religious-magical landscape. Phisanu, a concept with Buddhist, Hindu, and animist origins, refers to a substance said to exist both inside medicinal plants and the body of the healer. It is this substance, which is activated when the healer ‘blows’ a mantra on the medicine or the person he is treating, that gives the medicine its power. The healers describe how Phisanu is produced and destroyed through their adherence, or lack of it, to regulatory principles of plant collection and behaviour. One rule is that the healers cannot directly charge money for their services, and must rely on donations given according to Buddhist principles. Plant harvests are governed by astrological principles based on days of the week and time of the day, related to a wider “grammar of healing” in which astrology is applied to diagnosis and treatment. This means that only one part of the plant can be taken at a time, to allow it to continue growing.

Whilst these ‘rules’ may be loosely interpreted in reality, they nonetheless create an ethical framework which prevents both the exploitation of patients for profit and the over-harvesting of medicinal plants in the wild. In common with other indigenous approaches to plant use linked with spiritual principles, this has wider implications in addressing the unsustainable collection of wild medicinal plants, which has led to many species becoming endangered in Southeast Asia. In Laos, illegal exports of medicinal plants combined with deforestation and development means that it has becoming increasingly difficult for the often elderly healers to find the materials they need to treat those in their communities.

Towards an ecological medicine?

This short overview has demonstrated the multiple ways in which plants are ‘like people’ and how the symbolic and phenomenological links between plants and humans have ecological and medical implications. In Laos, relationships between humans and plants are an important part of local cosmologies that shape conceptions of medicinal efficacy. This is a motivating and regulating factor in ensuring ethical treatment of patients and developing sustainable approaches to plant use. Furthermore, this principle helps us to understand how culturally mediated human engagements with the environment both produce and shape medicinal knowledge in the form of plants used as medicine. This intersects with scientific definitions of efficacy, such as in the correlation between bitter tasting herbs and fever, or in the improved healing outcomes associated with increased participation by the sick person in their treatment process.

While not all of us live in rural villages, it may be worth reflecting on how our everyday interactions with plants impact how we think about health, the environment and inter-species collaborations. What kind of ecological-medicinal knowledge do we possess without realising it, and what motivates us to act in ways which lessen our negative impact? How can we reframe our assumption that agency is only found in humans? The question of whether the COVID-19 pandemic has weakened or increased the human environmental footprint has no straightforward answer, but it has perhaps increased the value many of us place on our health and on green spaces, such as in Singapore. At the same time, the contested nature of medical legitimacy during the period of pandemic-induced anxiety warrants a re-examination of how we think about ethics in healthcare. This generation of traditional healers may be the last in Laos, but if we are willing to learn, they may have important lessons to share with us today.

The views expressed in this forum are those of the individual authors and do not represent the views of the Asia Research Institute, National University of Singapore, or the institutions to which the authors are attached.

Elizabeth is a Medical Anthropologist working primarily in Laos. Her research interests are in three main areas: Asian traditional medicine, applied anthropology in public health, and anthropology of the body and wellbeing. Her fieldwork included ethno-pharmacological documentation of traditional herbal knowledge, leading to collaborative interdisciplinary research on the treatment of malaria. Her research also contributes to a broader understanding of wellbeing and healthcare use in Laos through study of healing ritual, relationships with plants and therapeutic encounters.