Religion going viral: Pandemic transformations and ritual performances in Asia

https://doi.org/10.25542/cte8-2282

Research during a pandemic has to face a whole set of different ethical and epistemological challenges. We may not be able to conduct participant observation, hang out with research participants, and get involved in traditional off-line and face-to-face interactions ‘on the field’.

The pandemic forces us to find new research modalities, that are necessarily collaborative, dialogical, and experimental. Even old-school ethnographers had to step out of their remote-village-setting and acquire new methodological skills to conduct netnography, or digital ethnography.

In this scenario, with a few colleagues at ARI we decided to launch a research blog called CoronAsur: Religion and Covid-19 as a platform to collect new empirical data and discuss religious responses and ritual innovations during ‘corona times’.

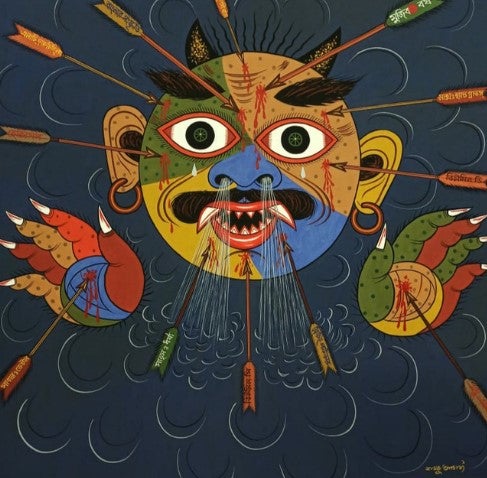

The name deserves a short explanation. On the occasion of a particular festival, in Mumbai, people built and subsequently burnt effigies of the Coronavirus representing it as a demon, using traditional iconography and local mythological traits to configure the corona-demon (corona-asur).

In Bengal, the community of scroll-painters and singers of stories, called Patua or Chitrakar, started to represent the spread of the virus – once again represented as a demon – in pictorial and sonic ways.

In Bangladesh the demon named Corona can be defeated through twelve material and metaphorical arrows. These weapons bear names such as Dettol soap, face masks, and Vitamin C, but also ‘courage and righteousness’, ‘Bengali culture’, and ‘cardamom and cinnamon’, known for their traditional medical properties.

These creative artefacts tell us that Covid-19 is not only under the microscope of scientists. It has already entered the fabric of cultural environments through traditional understandings of the relationship between human, nonhuman and disease.

When the term coronavirus entered our everyday vocabulary, the life of researchers in the humanities and social sciences witnessed several disruptions. Fieldwork plans have been cancelled, conference trips have been postponed indefinitely, and the head space to concentrate on one’s research project has been constantly undermined by a bombardment of worrying news, concerns, and insecurity.

Besides panicking and complaining about the difficult task of doing research during a global health crisis, at the Religion & Globalisation research cluster we decided to embrace the coronavirus as something to think with, realising that the social and cultural life of a virus has a lot to teach us about the human, the invisible, and the politics of power in 21st century Asia. In March, we started a research initiative called ‘Religious responses to Covid-19 and ritual innovations’.

The pandemic affected the ways in which people practice their religiosity; at the same time, people’s religious and cultural background influenced the ways in which they understand and counteract the viral outbreak. Lockdowns and social restrictions changed our everyday spiritual life, but also our everyday habits to cultivate mental and bodily well-being.

To give a first-hand example, these are a few facts that signalled the adoption of out-of-the-ordinary practices in my personal life. During the Indian lockdown, my guru suggested to all his students a daily breathing exercise, to be repeated once during daytime and once in the night time, connecting the heart plexus to the rest of the body.

This was not part of our ‘normal’ routine of breathing practice. Women of this community created a WhatsApp group to stay in touch during the lockdown and participate in various activities of aid and relief.

Members of the spiritual community I participate in who sing for a living, known as Bauls, were greatly distressed because of the Indian lockdown and the prohibition on meeting.

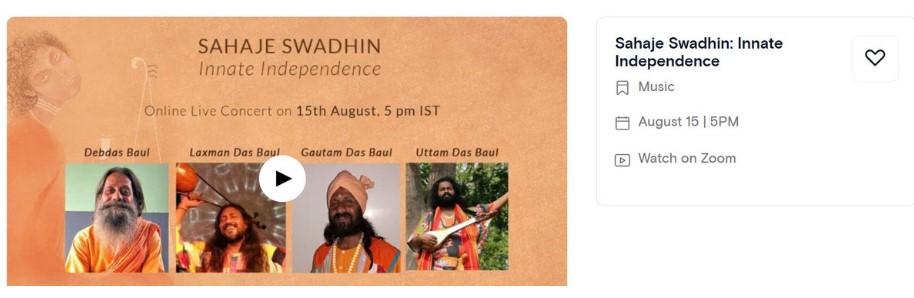

Sahaj Shakti (Innate Power), the second online concert organised by the Dara Shikoh Centre for the Arts on 17th October 2020

Students and disciples of the same guru mobilised to collect donations and deliver groceries and essential goods to the households of itinerant singers. Others helped these folk performers by organising live concerts via Zoom, devolving all the income of tickets and donations to the families of the artists.

These incidents offer insight into individual experience. However, similar transformations and the emergence of new phenomena of practice, solidarity, and togetherness, are visible also at a bigger scale – the meso-scale of religious institutions, and the macro-scale of societies. Both are apt domains of intellectual inquiry for the modern scholar of religion.

This is precisely how the research project ‘Religion Going Viral: Pandemic Transformations of Religious Lives and Ritual Performances in Asia’ started by reflecting upon casual remarks, individual experiences, and random observations at the cusp of religion and society.

In late February an academic visitor in Singapore went to church and was surprised to receive a disposable q-tip to apply the holy water without touching it with her fingers. She did not shake hands during the mass, and exchanged instead a contact-less sign of peace.

This was just before the global series of lockdowns, when a number of religious institutions and places of worship closed, suspended their gatherings or moved their rituals online. With my cluster colleagues, we started to discuss these ritual innovations and religious responses to the Covid outbreak: are these solely temporary changes, provisional safety-measures and digital arrangements that will be forgotten at the end of the pandemic? Or are these long-lasting changes that will affect the ways in which people engage with their communities, gods, deities and ancestors?

In Indonesia, the payment of the zakat (almsgiving) online through mobile phone apps increased tremendously during this last Ramadan, because of the pandemic. There is a good chance that people will continue to use phone apps to pay zakat even after the pandemic because it is convenient and they have them already on their phones, a finger tip away.

In Hindu temples, the prasad – that is, the offerings of food that is blessed by the deity and then shared among the devotees – is normally given by hand from the priest to the devotees on the spot. But now the devotee can collect a packaged prasad in a sanitised personal bag and take it to eat at home. This arrangement might not persist, because it could be perceived as incompatible with the fundamental value of communal sharing and sensory partaking of consecrated food (what Pinard called a digestive theology of ‘gustatory exchange’; 1991, 228).

These questions have profound methodological and theoretical implications for scholars interested in the material and aesthetic life of religious communities in Asia. However, when ethnographers are stuck at home and immobilised by strict travel bans, how can we collect the empirical data that is necessary to understand and analyse new phenomena at the interface of religion and societies in Asia?

Blog as method

The blog CoronAsur has been growing steadily since May, and it now constitutes a veritable living archive. It is a precious and expanding source of primary data and unique material to study religion during Covid in Asia, across a variety of regions and religious communities.

Documenting contemporary phenomena in such a vast scale would have been impossible for an individual scholar or a limited number of cluster research fellows. What makes this possible is the collaborative and informal nature of an online research blog.

A large number of posts discuss the interactions between religion and media, and the use of new media for online worship. Browsing through the blog one can read about the virtual bathing of the baby Buddha statue for the festival of Vesak, or the use of live streaming and ‘liturgical televisuality’ in the Catholic churches of the Philippines. These posts raise questions about the way in which new media engage or disengage devotees and how they reproduce or transgress the traditional concept of congregation.

The format, the agility and the promptness of a blog platform allowed us to host data from specialists, like religion scholars, but also perspectives and reflections from community members, leaders and activists, in a way that is less elitist and more immediate than an academic journal.

It also allowed us to share new findings swiftly, for free, and with a wider audience. Journeying through the homepage one can see lingji practitioners meditating in socially distant circles in Taiwan, and vessels of turmeric and neem leaves appearing in front of Hindu temples in Singapore, since these plants are part of the medicinal and ritual Hindu repertoire associated with purification.

In the era of social distance, social sciences workers have to rely upon each other more than ever, engaging in unprecedented patterns of international partnerships, with new modalities of collaboration. Because of the very sudden and critical circumstances, these cannot easily be institutionalised or funded as official research collaborations between countries, universities and institutes.

An interesting document in the form of a collective Google Doc started to circulate in professional mailing lists of anthropologists since April (Lupton 2020). It describes the ‘remote fieldwork’ activities that one could engage with during a pandemic. Many of these activities rely upon an internet connection or at least a working smart phone, leaving unaddressed the thorny question of class, age, gender gap and digital divide, and how this affects the kind of data collected with such modalities.

However, this document in itself is a telling example of doing research during a pandemic. It is a crowd-sourced document that relies upon the input and collaboration of numerous international researchers. Similarly to our research blog, it is a bottom-up initiative with loose hierarchical constraints, published online, freely accessible and open to all web users.

Born out of necessity in the troubled times of academic life during Covid, these research and output modalities are signalling the need for changing public ethics of collaboration. Apart from being emblematic of the present of academia in times of crisis, they are also steps towards a more inclusive and accessible future for academic practices of knowledge production and dissemination.

Carola is the author of Folklore, Religion and the Songs of a Bengali Madman (Brill, 2016) and is currently writing a new book on the sounds of religion, caste and displacement in the Bay of Bengal, focused on the Matua community.