Shifting Regulatory Regimes of Agribusiness and Plantation Investments in Southeast Asia: From RSPO to ASEAN-RAI

Southeast Asia is a hotspot for large-scale agribusiness and commodity crops, including palm oil, rubber, banana, maize, cassava, and sugarcane. These commodities have generally been framed by governments as mechanisms for poverty alleviation, engines of rural development, and important sources of foreign exchange for their countries. However, the commercialisation and intensification of these crops have resulted in the conversion of millions of hectares of land in Southeast Asia since the 2000s. In the process, environmental issues have frequently emerged, like deforestation, soil degradation, chemical runoff, fires, and human-wildlife conflict, as well as social concerns like land rights conflicts, access issues, and worker rights violations. Although governments are traditionally expected to address these issues through laws and regulations, command and control, quotas, and economic measures, the challenge of balancing economic and socio-environmental interests has often limited their effectiveness.

Various guidelines and notions of responsible investment have arisen to address these governmental limitations, offering different frameworks to address the persistent problems affecting rural landscapes and people. Hence, a shift from “government” to “governance” can be observed. But to what extent can we expect guidelines and certification schemes to influence positive changes in investor practices? This piece explores the shifting regulatory regimes of agribusiness and plantation investments in Southeast Asia. It first focuses on the palm oil sector, one of the most regulated agro-industrial commodities in the world. It then touches on developing regulatory regimes for rubber and concludes with reflections on how the ASEAN Guidelines on Promoting Responsible Investment in Food, Agriculture and Forestry (ASEAN-RAI) may contribute to the streamlining of these various regulatory regimes for agribusiness in the region.

Shifting Regulatory Regimes of Palm Oil

Palm oil plantation expansion has been identified as a major driver of deforestation and carbon emissions in the tropics and a grave threat to endangered animals within these areas. These environmental concerns inspired civil society-led consumer boycotts of items containing palm oil, mainly in “Western” markets, meant to shame and pressure various actors along the palm oil supply chain into “cleaning up their act”. Producer states, such as Indonesia and Malaysia, have reacted negatively to these boycotts, arguing that they are a form of “covert imperialism”; Indonesia and Malaysia, in particular, have painted a picture of NGOs not driven by universal environmental values, but by Western interests intent on protecting their own oilseed markets and keeping developing countries in poverty. One of the weaknesses identified by such “regulation-by-NGO” efforts was the lack of democratic accountability—only one type of stakeholder (NGOs) was shaping the agenda, which was often at odds with the interests of other stakeholders like governments, corporations, and sometimes also local communities.

Workers harvesting Oil Palm Fruits. Shutterstock.

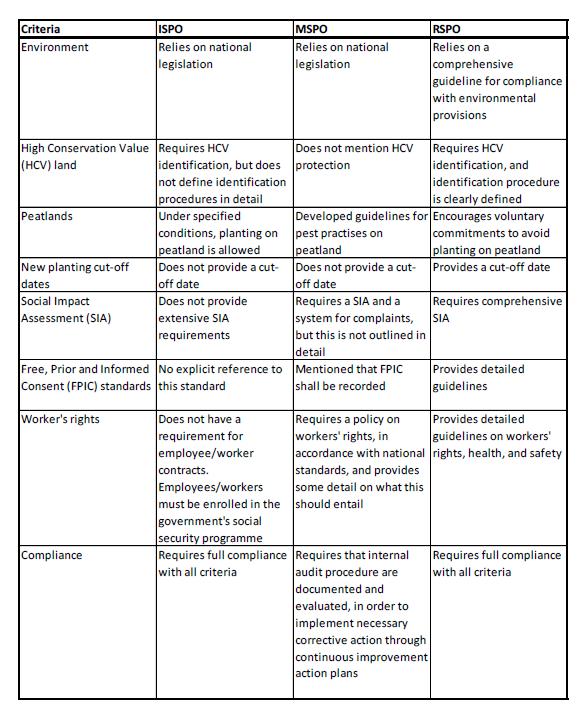

This eventually led to Indonesia’s withdrawal from RSPO in 2011 and establishment of the Indonesian Sustainable Palm Oil (ISPO) certification scheme, which was made mandatory the same year. While Malaysia remains with the RSPO, it also established the Malaysian Sustainable Palm Oil (MSPO) scheme in 2014, which was mandatory in 2017. Both countries also jointly founded the Council for Palm Oil Exporting Countries (CPOPC) in 2015 with the specific aim of harmonising the MSPO and ISPO schemes. Figure 1 presents a comparison of the three schemes. Their key points of departure (RSPO being voluntary, corporate- and standards-driven while ISPO and MSPO being mandatory, legislation-driven) have led to the that “RSPO pushes the ceiling (larger corporations, more stringent requirements), while ISPO and MSPO raise the floor (basic requirements, smallholders)”. It has also been argued that because the ISPO and MSPO are legally required and backed by the state, they can be more effective, even if less stringent.

Comparison of ISPO, MSPO, and ISPO. Adapted from EFECA. Courtesy of the authors.

While these various regulatory regimes can be seen as complementary to each other, general issues remain. There remains a lack of demand for sustainably certified palm oil, be it RSPO, ISPO, or MSPO. For RSPO, the most well-known of the schemes, only about 50% of RSPO-certified palm oil can be sold at a premium. There seems to be a mismatch between the rhetoric preferring sustainable palm oil and the willingness of buyers to pay premium prices for it. Furthermore, despite being considered the most stringent scheme among the three, RSPO is still not recognised as meeting EU Renewable Energy Directive II (RED II) biofuel requirements. These various regimes also raise the issue of differing definitions of sustainability–which scheme is “most accurate” in its standards for sustainability?

Developing Regulatory Regimes for Rubber

While consumer pressure played an important part in encouraging the development of palm oil regulatory regimes, this was not necessarily the case for rubber, a prominent crop in almost all Southeast Asian countries. Consumers spend little time thinking about the rubber in commodities they purchase, such as car tires and shoes, especially the social and environmental conditions of its production. However, researchers and civil society groups have raised the alarm about the social and environmental impacts of rubber plantations that have rapidly expanded into new landscapes in Southeast Asia. Much like oil palm, rubber plantations can lead to deforestation, biodiversity loss, agrochemical pollution, land grabbing, and labour rights abuses. Such reports played an important role in convincing actors in the rubber industry to respond by developing initiatives for improving sustainability. They were also influenced by sustainability trends across a wide range of industries and the potential to improve market access and prices.

A villager and her daughter collecting latex in their rubber field. Photo courtesy of Kenney-Lazar.

Voluntary guidelines for rubber have begun to emerge. The International Rubber Study Group (IRSG), an intergovernmental organisation of rubber-producing and -consuming countries, produced the first initiative in 2015 labelled the Sustainable Natural Rubber Initiative (SNRI). However, it has not been widely adopted by industry actors. Two newer guidelines emerged in the following years: the Chinese Chamber of Commerce of Metals, Minerals & Chemicals Importers and Exporters (CCCMC) Guidance for Sustainable Natural Rubber and the Vietnamese Guidelines on Mitigating Socio-Environmental Risks for Vietnamese Outwards Investors in the Mekong Subregion (VGIA). However, most prominently, a multi-stakeholder initiative was launched in 2018 by multinational tyre companies, the Global Platform for Sustainable Natural Rubber (GPSNR), which included member companies representing more than half of the globally traded natural rubber. These initiatives focused on establishing voluntary principles and standards for legal compliance, environmental protection, and respect for human rights in the sector.

These various platforms are in the early stages of implementation, focusing on pilot projects, training, and capacity building, as well as creating handbooks and risk analysis tools. Like with the RSPO, they could be critiqued for their voluntary nature, which has the potential to “greenwash” the industry. They are largely led by the private sector and have little direct government involvement. They also tend to gloss over past injustices and unsustainable practices; instead focusing on current production. Considering that there is little public awareness of the socio-environmental risks associated with rubber, questions remain concerning how such initiatives will be held accountable. Unlike palm oil regimes, there is no systematic certification system, but a scoring system that rewards continuous improvement of all actors involved. The effectiveness of such an approach is yet to be seen.

A Regional Framework for More Responsible Agribusiness

The ASEAN-RAI guidelines are a regional-level multi-stakeholder regulatory framework working to promote more responsible investment in food, agriculture, and forestry in ASEAN that contributes to regional economic development, food and nutrition security, food safety, and equitable benefits, as well as the sustainable use of natural resources. The ten guidelines engage with many other standards like Free, Prior and Informed Consent (FPIC), International Finance Coalition (IFC) performance standards, and Social and Environmental Impact Assessments (SIA/EIA). They are largely based on the preceding RAI guidelines of the Committee for World Food Security but adapted for ASEAN with a greater emphasis on forests, diffusion of technology, and regional cooperation. The figure below depicts the 10 ASEAN-RAI guidelines and some of the policies and standards that intersect them.

Governance domains of the ASEAN-RAI Guidelines and interlinked policies and standards. Published in Cole, 2022.

Along with navigating existing commodity-specific regulatory regimes, governments are expected to integrate the guidelines into their policies. However, in the tradition of the “ASEAN way”, the guidelines remain non-binding, with generally soft language, few targets, and the omission of certain key aspects (such as how to manage the unsustainable use of agrochemicals). In turn, private agribusiness investors, financial institutions and related government agencies are meant to adopt the guidelines in their operations. Although several regional companies have expressed interest in applying the ASEAN-RAI guidelines, these often tend to be the kind of firms already concerned with their brand image and investing in environmental and social sustainability. An underlying critique of RAI is that having more large-scale agribusiness is not the answer to most of the challenges rural people face in developing countries. But as much as the emphasis should be on supporting vulnerable smallholder populations and diverse landscapes, it is also clear that agribusiness investments will continue as global demand for cheap agro-commodities increases unabated. Accepting that large-scale agribusiness will be part of global agri-food systems means that principles and guidelines for reducing and avoiding negative impacts are also part of the solution.

As a regional initiative, ASEAN-RAI has the potential to bridge different jurisdictions more effectively so that companies can be held accountable for impacts across the value chain. The RAI principles do so by increasing the visibility of bad investment practices in national and regional policy agendas, thus reducing the operating space of such companies. Meanwhile, more brand-conscious firms can lead the way and influence the wider sector in which they work, and binding legal frameworks can be gradually influenced by the content of soft laws as RAI begins to enter and inform agricultural policymaking spaces among ASEAN governments. In these ways, despite their non-committal nature, the RAI guidelines may exert a longer-term influence on regulations that ultimately curtail damaging agro-investment practices, in concert with the heightened spotlight on and debate around social and environmental impacts than in the recent past. In this regard, there are parallels with the rising concerns in the rubber industry. Once the full consequences of the rubber industry for Southeast Asia were more widely publicised, Sustainable Natural Rubber (SNR) approaches have followed and have since begun to align with RAI principles. What is needed in all cases is recognition that many firms are still able to externalise and avoid addressing negative impacts from plantations, and often gain a competitive advantage by doing so. This is the challenging paradox that guidelines and certification schemes need to address to be able to steer agribusiness towards more beneficial outcomes for Southeast Asia’s rural communities and landscapes.

Conclusion

This dense field of multiple regional-level and commodity-specific regimes can be challenging and discouraging to navigate. However, they are becoming harder to evade as we enter this “era of the voluntary guideline”; this “moment of intense production of international instruments” of soft law and “quasi-authoritative rules that transcend national borders”. Indeed, while mandatory regimes like the ISPO and MSPO may be unavoidable, the adoption of voluntary regulatory regimes by early movers may influence other firms to follow suit. Furthermore, particularly in landscapes where government command and control are constrained, voluntary regulatory regimes such as SNR frameworks and the ASEAN-RAI Guidelines can move sustainability issues up the policy agenda, creating challenges for problematic investors. In these ways, these “soft” laws and governance instruments may influence hard laws–“governance” possibly influencing “government”.

However, several challenges remain. First, it is necessary to convince governments, corporations, and smallholders that socio-environmental sustainability should be an important part of their business model. Second, the competitive advantage laggards enjoy for sidestepping costs related to sustainability processes must be reduced. And finally, local, regional, and international markets must commit to purchasing (possibly more costly) sustainable products. All these will support a continued shift toward more sustainable and responsible agriculture and plantation investments in Southeast Asia.

This article has benefited from financial support provided by the Ministry of Education, Singapore, under its Social Science Research Council (SSRC) grant “Climate Governance of Nature-based Carbon Sinks in Southeast Asia” (MOE2021-SSRTG-021). Any opinions, findings and conclusions or recommendations expressed in this material are those of the authors and do not reflect the views of the Ministry of Education, Singapore nor of the Asia Research Institute, National University of Singapore.