Why can(‘t) Indonesia’s longest serving president, Suharto, be granted National Hero honour?

Figure 1: After 31 years as Indonesia's longest-serving president, Suharto reads his resignation speech at Merdeka Palace on May 21, 1998, with his successor, B. J. Habibie, by his side. (Source: Wikipedia)

Figure 1: After 31 years as Indonesia's longest-serving president, Suharto reads his resignation speech at Merdeka Palace on May 21, 1998, with his successor, B. J. Habibie, by his side. (Source: Wikipedia)

In April 2025, the Indonesian government’s renewed proposal to confer the title of Pahlawan Nasional (National Hero) upon the second president of Indonesia, Suharto, sparked intense public debate. For many, Suharto remains a profoundly polarizing figure: credited as the Bapak Pembangunan (Father of Development) who drove Indonesia’s economic growth, yet condemned for decades of authoritarianism, corruption, and human rights violations.

This is not the first attempt to sanctify his reputation; similar proposals surfaced in 2008 and 2010. But this 2025 nomination carries new weight. According to Indonesian regulations, a person can only be proposed for the title three times. This is the third and final opportunity for Suharto’s supporters to secure his place in the national canon.

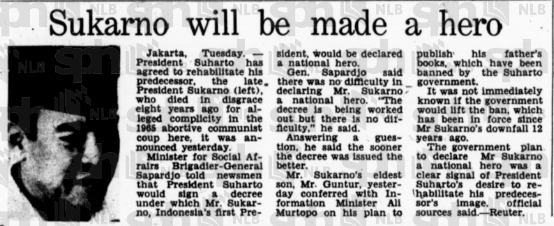

The designation of a national hero is never merely about personal legacy. It is a political act that reflects the state’s shifting priorities. Heroic canonisation in Indonesia often peaks around Hari Pahlawan (Heroes’ Day) each 10 November. By linking Suharto’s “service” to this national ritual, proponents seek to fold authoritarian order into the moral narrative of independence. The state has previously honoured complex figures, including former Vice President Sultan Hamengkubuwono IX and even Sukarno, whose posthumous rehabilitation Suharto personally authorised in 1978 after years of suppressing his image.

Figure 2: A 1978 New Nation report on Suharto's plan to designate Sukarno a national hero. Source: National Library Board, Singapore. Source: National Library Board, Singapore

The Pahlawan Nasional title remains Indonesia’s highest state honour, and the process is intensely political. The 2025 proposal also recommended Sumitro Djojohadikusumo, an influential economist under the New Order regime and father of current president Prabowo Subianto. Supporters of Suharto’s canonisation point to the tangible achievements of his regime: political stability and economic growth that lifted millions out of poverty. These memories fuel a potent nostalgia for the perceived order of the New Order, especially when contrasted with the turbulence of the democratic years that followed.

Debates around national hero nominations resurface periodically, often tied to the political significance of both the individual and the contemporary moment. Each time Suharto has been nominated, the same debates have resurfaced: supporters emphasise economic stability and order, while critics recall repression and bloodshed under his regime. The Ministry of Social Affairs which oversees the award has acknowledged the controversy, promising to listen and take it into consideration.

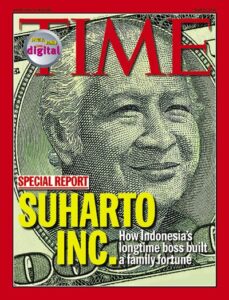

Figure 3: Suharto Inc. May 24, 1999: a four-month TIME investigation reveals that former president and his children controlled assets worth US $15 billion. Source: TIME.

Yet this story of progress rests on a violent foundation. Suharto rose to power after the 1965–66 anti-communist massacres that killed more than half a million people. His rule was marked by the silencing of dissent, military campaigns in East Timor, Aceh, and Papua, and the Petrus killings of the 1980s. His family’s vast corruption became notorious, draining billions from the state. For survivors and human-rights activists, honouring Suharto would not be an act of reconciliation, but a denial of suffering. This opposition remains fierce and organized: on November 4, 2025, a broad coalition of hundreds of academics, artists, activists, and labour unions held a press conference at the Indonesian Legal Aid Foundation (YLBHI) in Jakarta, publicly rejecting the nomination. Following this, the coalition began circulating a digital petition to build a broader citizen movement, aiming to create what they call a "living archive" (arsip hidup) of public opposition to honouring Suharto.

Previously in May 2025, human-rights groups including KontraS and international partners issued a joint statement rejecting the proposal to name Suharto a national hero. They argued that such recognition would legitimise decades of impunity for New Order crimes and betray the victims still waiting for justice.

This ongoing debate reflects what Derek Alderman calls “reputational politics”, or the contest to shape how a figure is remembered. Each attempt to rehabilitate Suharto helps political elites preserve their own legacy and revive the New Order’s values of order and obedience. Lee Kuan Yew once described Suharto as a man devoted to “Javanese stability.” Turning that trait into heroism serves a clear purpose today: it turns control into virtue and nostalgia into legitimacy.

This reputational contest also takes physical form. Suharto’s grand mausoleum, Astana Giribangun in Central Java, functions as a shrine where pilgrims continue to honour him, a lasting monument to the endurance of his power and myth.

Against this tide of rehabilitation, grassroots movements guard an alternative moral archive. The disappeared poet Wiji Thukul and the murdered human-rights lawyer Munir Said Thalib have become unofficial saints of Indonesia’s democracy. This counter-memory is not just symbolic; it is a living protest. For over 18 years, the Aksi Kamisan (Thursday Actions) have seen families of the disappeared—including victims of the 1998 abductions—stand in silent, black-clad vigil outside the Presidential Palace, becoming a living monument to state impunity. Their presence reminds us that heroism can also rise from below.

Figure 4: Sleman, Yogyakarta / Indonesia. This statue is in the museum which used to be the residence of Suharto's childhood. Source: Shutterstock.

The reputational battle also unfolds in popular culture. On social media, memes show Suharto smiling beside the caption “Piye kabare? Enak jamanku to?” (“How are you? Wasn’t it better in my time?”). These digital afterlives turn repression into entertainment, blurring moral distance through irony and humour. As memory scholar Sabine Marschall notes, public remembrance is never fixed but constantly reshaped. The New Order’s monuments of stone have simply migrated into the algorithms of nostalgia.

Figure 5: “Mengapa ‘merindukan’ sosok Suharto?” visual captures precisely the affective side of reputational politics: nostalgia rebranded as humour. Source: BBC

Figure 5: “Mengapa ‘merindukan’ sosok Suharto?” visual captures precisely the affective side of reputational politics: nostalgia rebranded as humour. Source: BBC

In the end, the question of whether Suharto can or cannot become a national hero is less about one man’s reputation than about Indonesia’s moral direction. How a nation remembers its past shapes the future. The rehabilitation of the Marcos family in the Philippines shows how nostalgia and revisionism can pave the way for the return of authoritarian politics. With Suharto’s former son-in-law, Prabowo Subianto, now president, efforts to sanctify the New Order’s founder are likely to grow stronger. Whether Indonesia can resist that impulse and build a more honest and inclusive memory culture will test the strength of its democracy.

The Suharto debate reveals a larger truth: once reputation hardens into heritage, it becomes difficult to separate memory from myth. To decide who deserves to be remembered as a hero is to decide what kind of nation Indonesia wants to be: one that continues to serve power, or one that finally begins to serve justice.

The views expressed in this forum are those of the individual authors and do not represent the views of the Asia Research Institute, National University of Singapore, or the institutions to which the authors are attached.

Dr Myra Mentari Abubakar commenced her NUS Fellowship with the Asian Urbanisms Cluster with effect from 9 December 2024.

She completed her PhD in 2024 at The Australian National University and is currently engaged in extensive research on the hero phenomenon across Indonesia and Southeast Asia. Affiliated with the International Centre for Aceh and Indian Ocean Studies (ICAIOS) in Aceh, her research primarily focuses on gender and cultural history with an emphasis on Indonesia. At ARI, Dr Myra will explore the complex dynamics of memory and heritage in urban settings. She seeks to shed fresh light on cultural and historical framework by tracing how sites of hero legacy and gendered narratives shape public spaces and collective memory within urban landscapes.

https://doi.org/10.25542/eccq-nr38