‘Would you move to a house with no toilet?’: The fishers of Jelutong jetty and the right to stay put

https://doi.org/10.25542/37zy-7788

If one sits on the wooden benches of the jetty of Jelutong when fishers gather to work on their rawai used for longline fishing, deep knowledge of and connections to the sea seem to emerge in every single word. Seng, for example, explained to us that they use octopus’ tentacles as baits for their rawai hooks, because fishes prefer octopuses just as people do. “It’s a luxury dish! Now even a fish is educated (ikan sekarang pergi tuisyen)”, he averred, implying that fishes have discerning taste. In this poetic outburst, Seng emphasized that sea creatures and humans are more similar that one thinks, even if species like octopuses are considered “mean” (jahat). “But they [octopuses] are just like us [humans], because they want to escape, to survive”, Seng added. His words remind us about a subtle connection between fishers and sea creatures. They are trying to stay put along the place they know the most, a land-sea interface under pressure because of constant land reclamation.

Preparing the rawai fishing longlines. Photo courtesy of the authors.

Preparing the rawai fishing longlines. Photo courtesy of the authors.

In the following, we focus on the fishers operating at the jetty of Jelutong, a suburb on the almost completely reclaimed eastern coast of Penang Island, where our fieldwork paths crossed last year while investigating the effects of land reclamation on coastal and fishing communities. Small Malaysian states like Penang resort to the reclamation of new land from the sea in order to generate new revenues and to finance ambitious infrastructure or real estate development projects. The creation of man-made land and islands is taken as an ideal option in order to avoid conflict over displacement on existing land. As Grydehøj notes, land-sea interfaces are approached as “a blank slate for development” because they “could be deemed immune from claims of publicness”. Littorals are approached as a mare nullius (“nobody’s sea”). Yet, land reclamation also entails “un-homing” processes which rupture connections between people and place, especially for fishers like Seng, those who depend most on such land-sea interfaces for their livelihood.

Based on spatial analysis and interviews, the next sections will present ethnographic insights on land reclamation and the ways the fishers of Jelutong rearticulate their right to stay put and navigate relocations.

View of the reclaimed shoreline from the Jelutong jetty. Photo courtesy of the authors.

View of the reclaimed shoreline from the Jelutong jetty. Photo courtesy of the authors.

Jelutong Reclaimed Landscape

Today, perhaps most Penangites do not realize that Jelutong was one of the earliest coastal settlements on the island. This land-sea interface was the primary source of livelihood not only for fishers, but also for charcoal makers who collected wood from the mangroves. But Jelutong shoreline has been radically transformed in the last decades. First came a landfill in the 1970s that was initially used as a dumping site (as seen in the map below). In 1992, it was designated as a sanitary landfill. After ten years, only construction waste was allowed to be dumped there. As for now, the site is still awaiting rehabilitation. Unsurprisingly, the media have been more attracted by concerns of local residents such as the gases released at the landfill. Such land-biased attention is symptomatic of the lack of interest on the effects at sea. Fishers from the Jelutong jetty are bearing the effects of such a dumpsite without any interest from the state or civil society: they report siltation issues and cannot fish in these waters.

The old and new jetties are separated by a landfill that has managed to attract its fair share of attention. Satellite image from Google Earth with the labels added by the authors.

The old and new jetties are separated by a landfill that has managed to attract its fair share of attention. Satellite image from Google Earth with the labels added by the authors.

Then came the Lim Chong Eu Expressway. The Penang State Government signed agreements with a private corporation awarding an expanse of to-be-reclaimed land in exchange for building the Expressway. This transport infrastructure project was envisioned in the mid-1980s to solve traffic congestion and connect the island from north to south. Because of a lack of funding, the Penang State Government signed a Privatisation Agreement with the IJM Corporation in 1997. As one of Malaysia’s leading conglomerates, IJM was allowed to reclaim more than 300 acres of land in exchange – new land from the sea to replace what was considered a squatting area with upscale real development projects.

Fishers from the Jelutong jetty had to relocate several times following the land reclamation works, until they settled at the existing location. The orientation of the old jetty at this location looks like the natural termination of an axis that connects Jalan Jelutong to the shoreline via Jalan Ahmad Noor. This makes sense from an urban design perspective – given Jelutong’s history of coastal villages – to celebrate this connection to the sea. However, as we approach the place, the 2-dimensional nature of maps that flattens all elements to one plane is often misleading. The whole coastline is now cut off from where people live and work by the Expressway that was itself built on reclaimed land. It is elevated to allow for ingress and egress to Jelutong – the result is a visual disruption of the abovementioned axis – but instead of celebrating the history of coastal villages, what is being celebrated is the Expressway. If one is not careful, one would miss the Jelutong jetty altogether. This situation exemplifies the phenomenon of how almost the entire northwestern urban fabric of Penang island is now disconnected from the coastline through land reclamation and the construction of major roads.

On the other side of the landfill lies a new facility provided by IJM for fishers in 2007. It has been named the Fisherman’s Wharf. The fishers were supposed to move to this new jetty built on the seafront promenade reclaimed by IJM because the site where their old jetty floats is planned for even more land reclamation. Costing almost RM4 million, the new facility is bigger with a more extensive jetty and a separate building for storage. Yet, the fishers still operate out of the old jetty that they put together themselves.

The Jelutong jetty. Photo courtesy of the authors.

The Jelutong jetty. Photo courtesy of the authors.

“This Is Our Place!”

Kamal, another fisher, told us: “We are nelayan [fishers] from Jelutong, you shouldn’t move us elsewhere. This is our place”. According to Kamal, the new jetty is considered incomplete and is not suitable for them. As Kamal added:

A lot of the things that we requested were not fulfilled. So we protest lah, we don’t want to move. It’s like you get a new house, but there is no toilet provided! […] To the state government and the developer, we are an obstacle [kami ni batu penghalang], “We’ve built you a new house, but you refused to move” [the state and the corporation say]. But the house is incomplete, how are we supposed to move?

Our interviews with fishers reveal that they have clear ideas about how a jetty should be.

The space where we talked to Seng and other fishers while they were mending the rawai is enveloped with shelves where these fishing longlines are kept with other equipment. Beyond this space is a kitchen and an entertainment system, such as a television and a stereo. Some tables and chairs are clustered around on the deck. Across the gangway is where the fishers weigh and sell their catch. On the wall, there is a board with the current market price according to the types of catch. The whole structure has an air of a clubhouse with the jetty extending further in one straight line. Even though there are no doors or gates, the spatial configuration makes it feel like we are in semi-private space.

Fish selling space at Jelutong jetty. Photo courtesy of the authors.

Fish selling space at Jelutong jetty. Photo courtesy of the authors.

On the other hand, the new facility at the Fisherman’s Wharf is bigger with a more elaborate jetty configuration. To some the new jetty would look more “beautiful” than the old one. “To the engineers and architects, it’s perfect!”, Kamal said. According to him, the new jetty seemed to be planned more to serve tourists than fishers. Kamal described the arrangement of the pontoons at the new jetty as more like a “car park”, contrasting it with the simpler configuration at their old jetty which provides them with an easier access to their boats. Also, a portion of the space in the Fisherman’s Wharf has been reserved for a restaurant. This means that there will be less space for the activities of the fishers.

The new jetty for Jelutong fishers. Photo courtesy of the authors.

The storage space is completely separated from the jetty by an access road that provides access to the shoreline. From the jetty, the storage space building looks like an inward-looking monolith. The spatial arrangement is simple – an open space in the middle is surrounded by individual storage units separated from one another by brick walls. However, the ceiling and doors are made of wire fencing. The open space where the mending of the rawai would take place faces a fence separating the storage space from the food court next door, instead of facing the jetty. Fishers refer to this place as a “cage” (sangkar).

The storage space at the new jetty. Photo courtesy of the authors.

The storage space at the new jetty. Photo courtesy of the authors.

The separation between the jetty and the storage space means that the fishers have to travel a longer distance to haul their equipment and supplies to their boats, and when they are back from the sea to haul their catch to the storage space. Kamal exclaimed: “Just imagine, if we come back from the sea at night with a lot of catch, how many trips would we have to make?” But this is a small matter; as Kamal told us, they can still find a way to make it work. Yet, there is a bigger problem at hand.

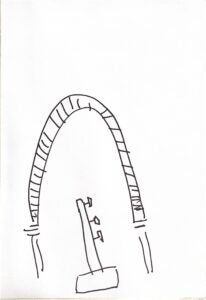

The biggest weakness of the new facility is the lack of a water breaker, crucial to prevent the huge tides and strong wind from wrecking the boats, pontoons, and the jetty. Without a water breaker, the boats and the structures are fully exposed to the forces of nature. Kamal pointed to something distant floating in the water, close to the landfill – it was a pontoon that had broken loose from their current jetty. Gesturing to a coil of thick rope close to where we were talking, he lamented that the tide can break the thick ropes that they use to secure the boats and the structures. As he was drawing his ideal jetty on a piece of paper, Kamal had a clear idea on the ways functional water breakers should be planned.

How Kamal envisions a functional jetty. Drawing by Kamal.

How Kamal envisions a functional jetty. Drawing by Kamal.

Even though the fishers have not moved yet to the new facility, it already needs extensive repair. Some of the pontoons have drifted away and the piling is not steady. For now, the developer is footing the bill. “If they want to repair or do anything, they should include the committee [of Jelutong fishers], so we can contribute our idea. Before they built this, they never consulted us,” Kamal told us.

Un-homing and the Right to Stay put along the Littoral

Land reclamation is a long-term process. While land is reclaimed, fishers have to accept relocations, and even the negative effects of land reclamation on their livelihoods because they know that it is inevitable. Yet, they are willing to actively contribute to the planning of fishing facilities based on their extensive knowledge of the land-sea interface. So far, however, their requests have been ignored. The fishers of Jelutong are still waiting for a proper jetty promised two decades ago.

People like Kamal and Seng are the most affected by land reclamation. According to them, fishers are considered by the state and developers not even as second class, but “third class” citizens. And, when they oppose such projects they are depicted as “anti-development” actors. This essay is a modest attempt to give space to their voices and their right to stay put along the littoral. As this case study shows, the practical needs of fishing communities, such as safe water breakers and more functional fish landing jetties instead of alluring touristy ones, should be taken into consideration more seriously by decision-makers.

The views expressed in this forum are those of the individual authors and do not represent the views of the Asia Research Institute, National University of Singapore, or the institutions to which the authors are attached.

Dr Nurul Azreen Azlan is a Lecturer in Architecture and Urbanism at the Manchester School of Architecture and whose academic focus leans towards the politics of space. As a recent Research Fellow at the Asia Research Institute, she examined the social impact of the Penang South Island Reclamation project on the coastal community in the area affected.

Pierpaolo De Giosa is a sociocultural anthropologist at the Department of Asian Studies of Palacký University Olomouc. His contribution is part of his Marie Skłodowska–Curie postdoctoral fellowship under the grant agreement number 101062825 funded by the European Union. Views and opinions expressed are however those of the authors only and do not necessarily reflect those of the European Union. Neither the European Union nor the granting authority can be held responsible for them.